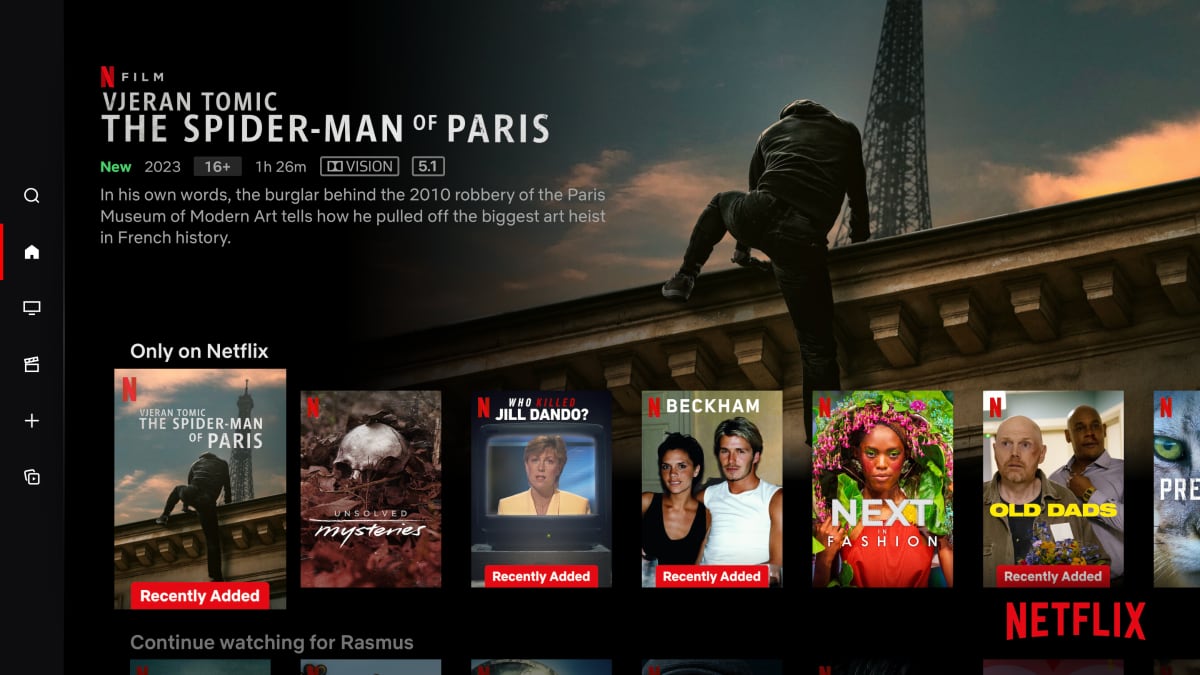

Artificial Intelligence isn’t new, but in November 2022, something changed. The launch of ChatGPT brought AI out of the background and into everyday life. Suddenly, interacting with a machine didn’t feel technical — it felt conversational.

Just this March, ChatGPT overtook Instagram and TikTok as the most downloaded app in the world. That level of adoption shows that millions of everyday users, not just developers or early adopters, are comfortable using AI in casual, conversational ways. People are using AI not just to get answers, but to think, create, plan, and even to help with mental health and loneliness.

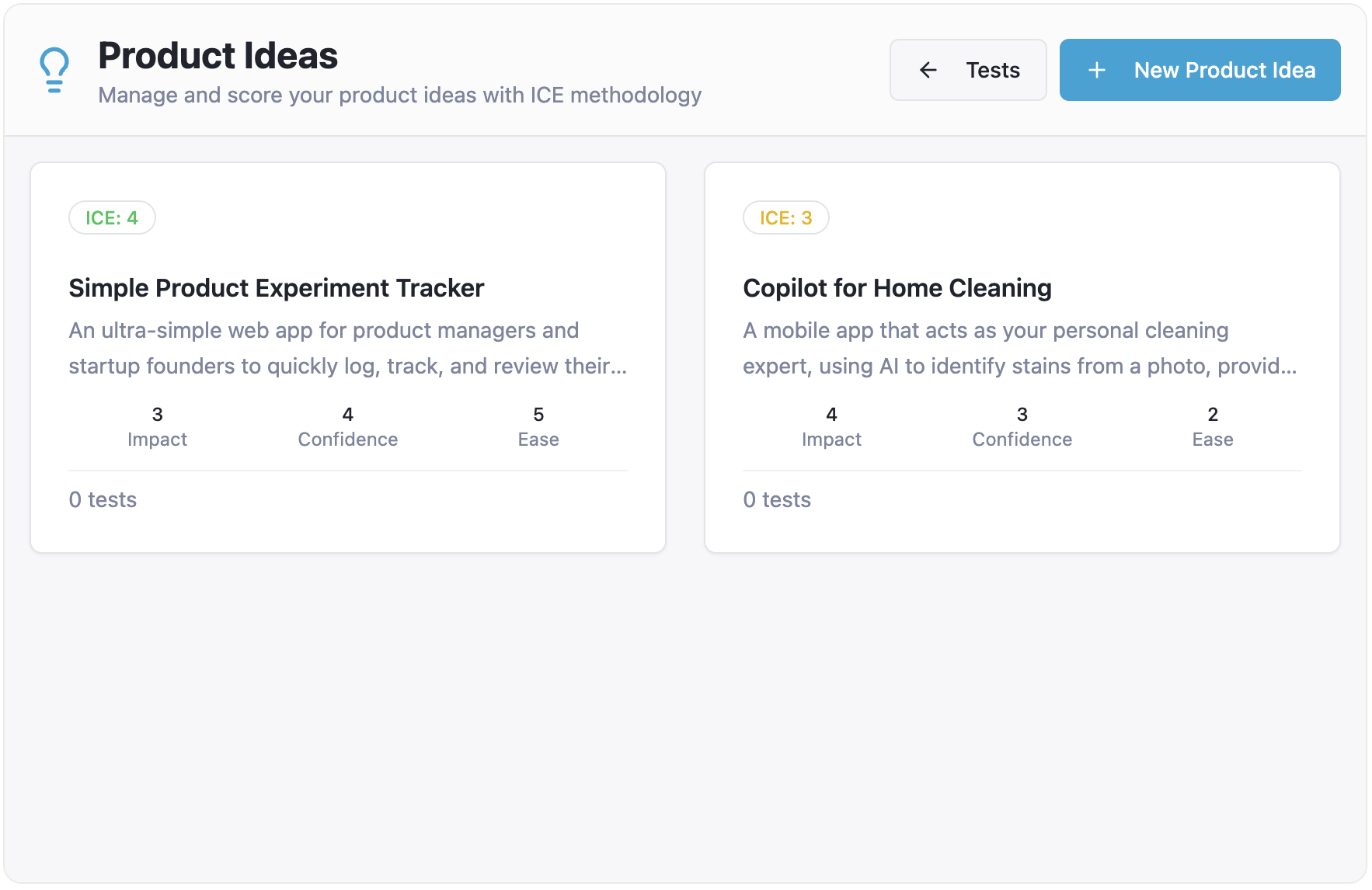

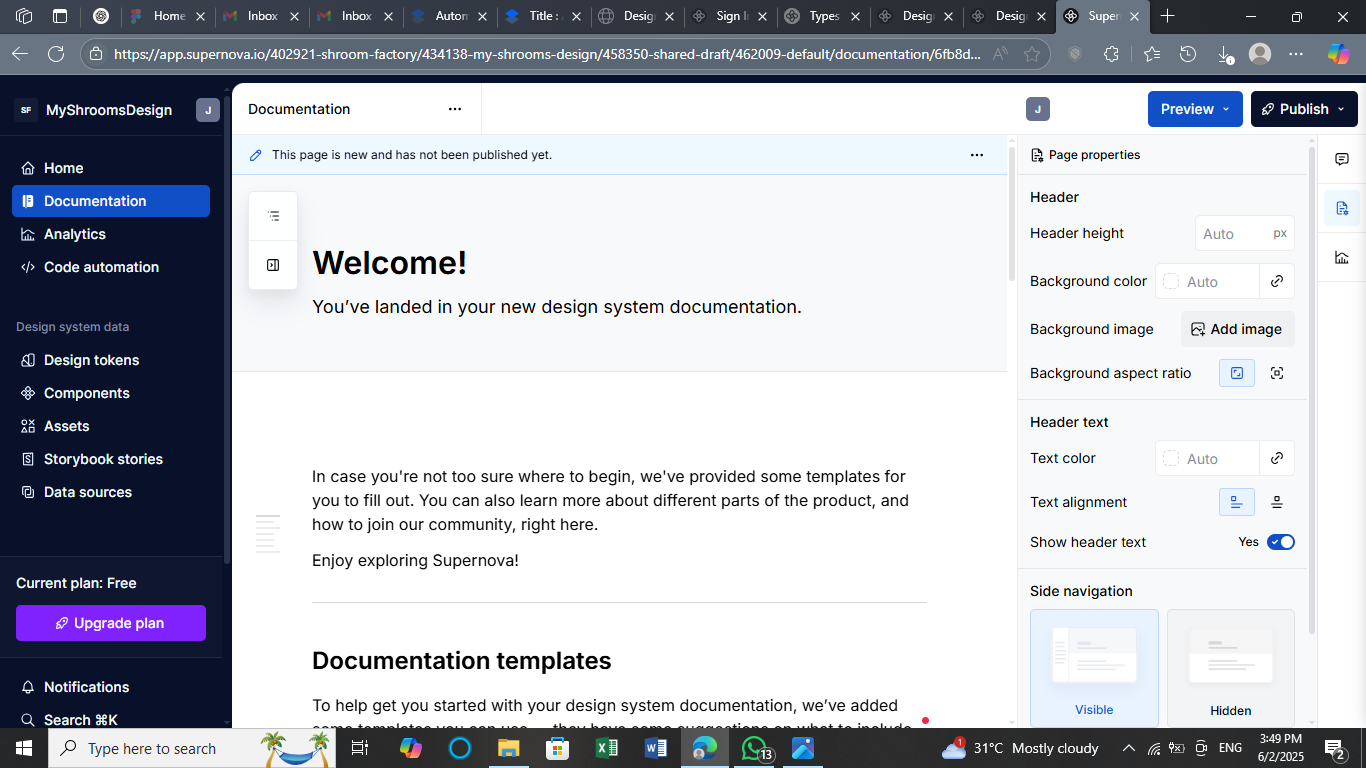

In the past two and a half years, people have moved through the Kübler-Ross Change Curve — only instead of grief, it’s AI-induced uncertainty. UX designers, like Kate (who you’ll meet shortly), have experienced something like this:

- Denial: “AI can’t design like a human; it won’t affect my workflow.”

- Anger: “AI will ruin creativity. It’s a threat to our craft.”

- Bargaining: “Okay, maybe just for the boring tasks.”

- Depression: “I can’t keep up. What’s the future of my skills?”

- Acceptance: “Alright, AI can free me up for more strategic, human work.”

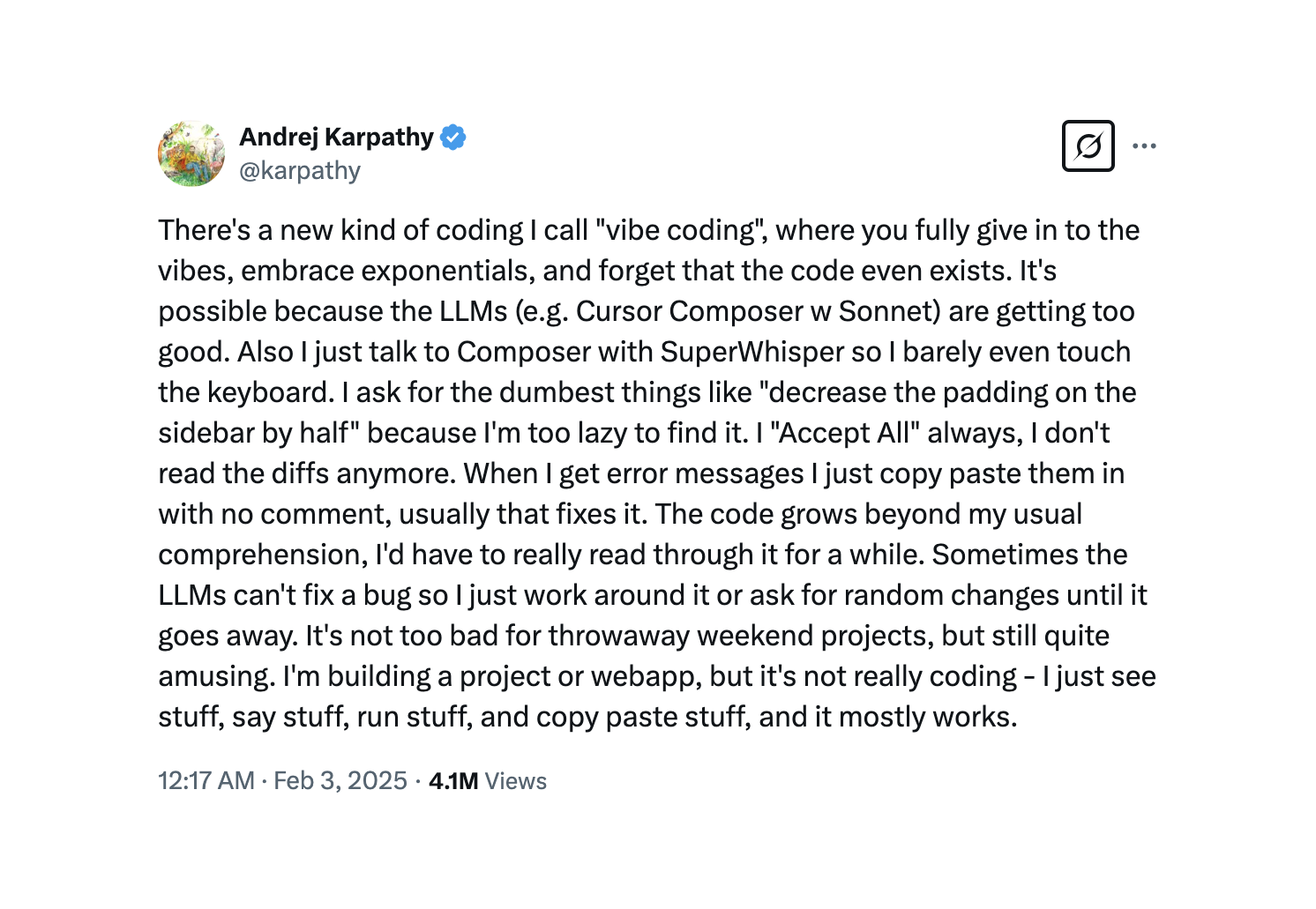

As designers move into experimentation, they’re not asking, Can I use AI? but How might I use it well?.

Using AI isn’t about chasing the latest shiny object but about learning how to stay human in a world of machines, and use AI not as a shortcut, but as a creative collaborator.

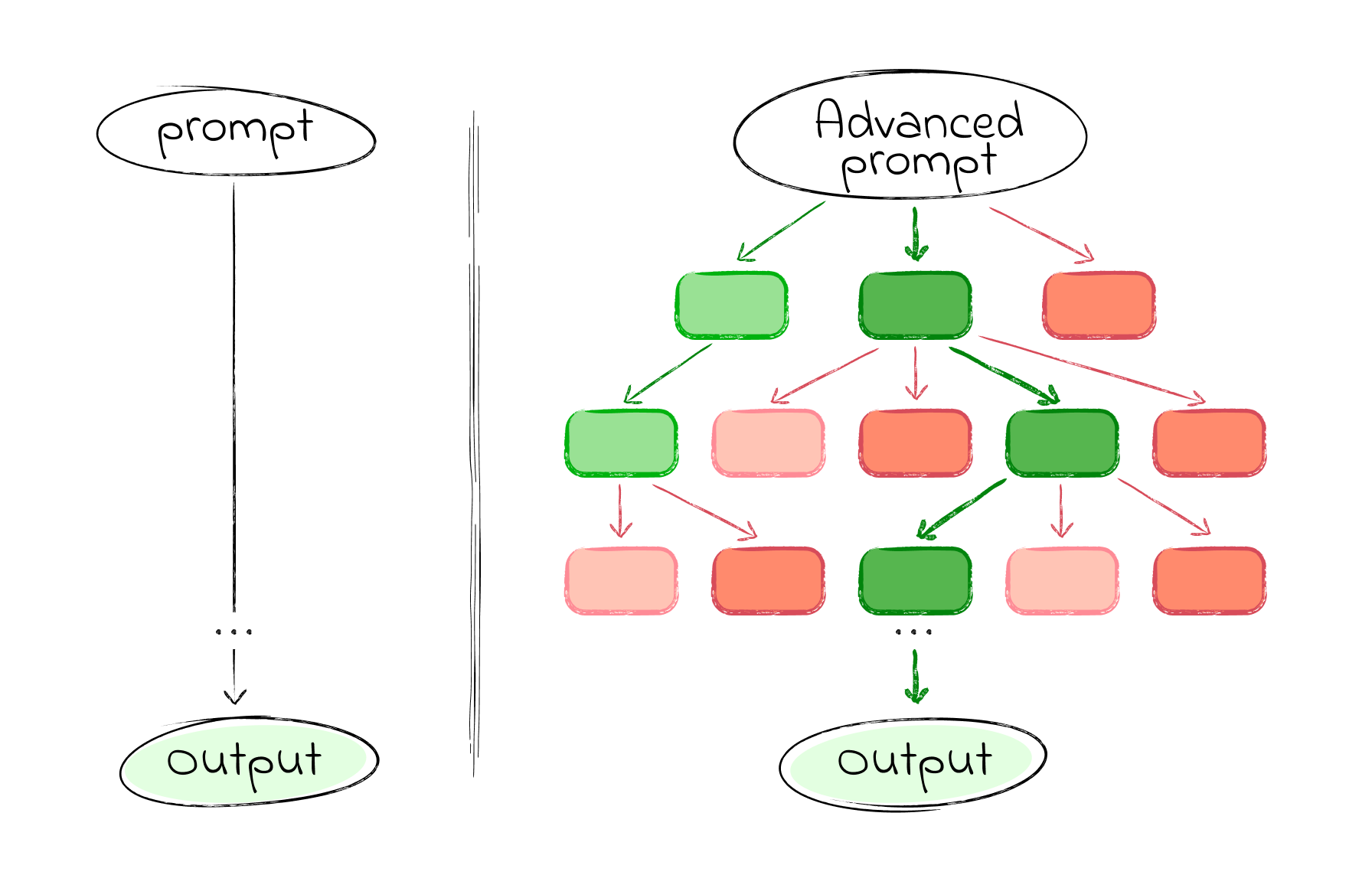

It isn’t about finding, bookmarking, downloading, or hoarding prompts, but experimenting and writing your own prompts.

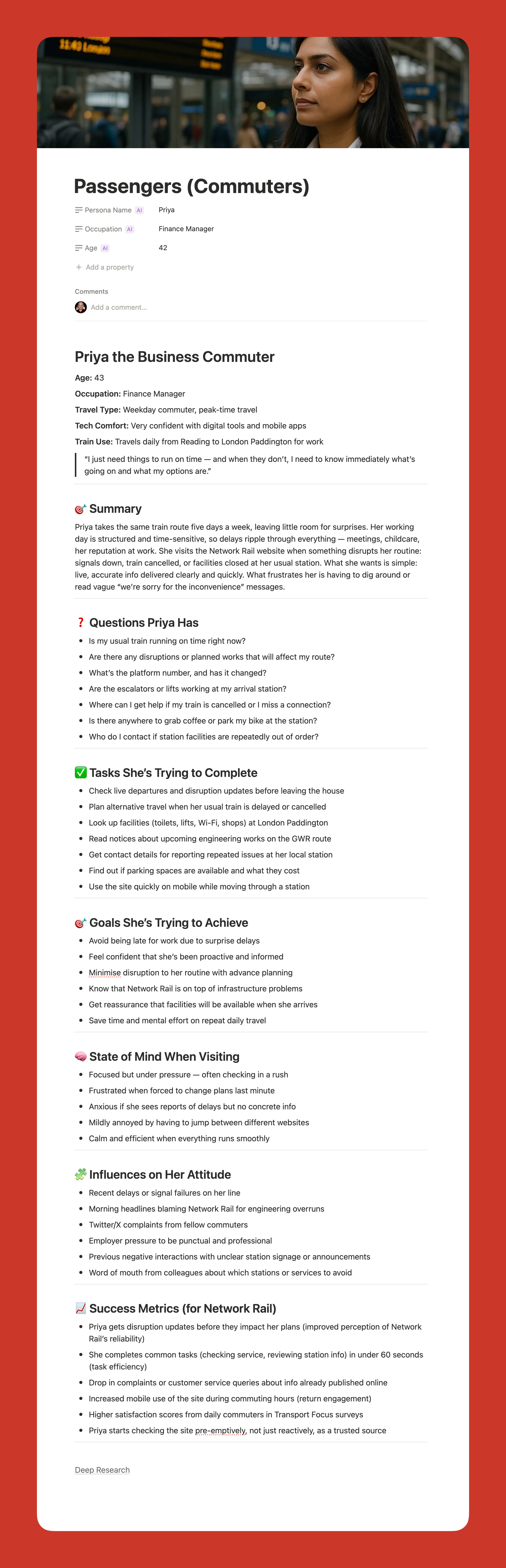

To bring this to life, we’ll follow Kate, a mid-level designer at a FinTech company, navigating her first AI-augmented design sprint. You’ll see her ups and downs as she experiments with AI, tries to balance human-centered skills with AI tools, when she relies on intuition over automation, and how she reflects critically on the role of AI at each stage of the sprint.

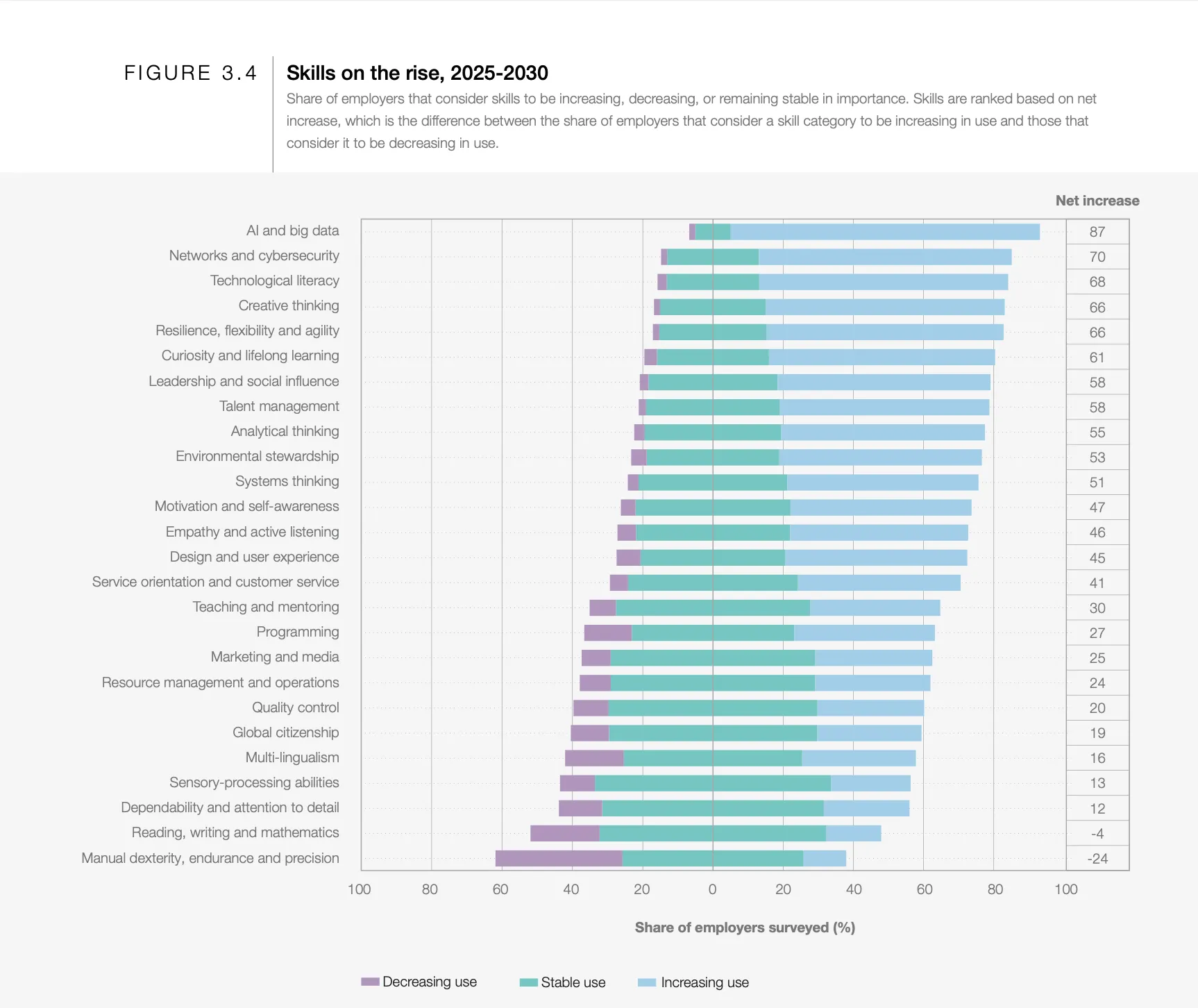

The next two planned articles in this series will explore how to design prompts (Part 2) and guide you through building your own AI assistant (aka CustomGPT; Part 3). Along the way, we’ll spotlight the designerly skills AI can’t replicate like curiosity, empathy, critical thinking, and experimentation that will set you apart in a world where automation is easy, but people and human-centered design matter even more.

Note: This article was written by a human (with feelings, snacks, and deadlines). The prompts are real, the AI replies are straight from the source, and no language models were overworked — just politely bossed around. All em dashes are the handiwork of MS Word’s autocorrect — not AI. Kate is fictional, but her week is stitched together from real tools, real prompts, real design activities, and real challenges designers everywhere are navigating right now. She will primarily be using ChatGPT, reflecting the popularity of this jack-of-all-trades AI as the place many start their AI journeys before branching out. If you stick around to the end, you’ll find other AI tools that may be better suited for different design sprint activities. Due to the pace of AI advances, your outputs may vary (YOMV), possibly by the time you finish reading this sentence.

Cautionary Note: AI is helpful, but not always private or secure. Never share sensitive, confidential, or personal information with AI tools — even the helpful-sounding ones. When in doubt, treat it like a coworker who remembers everything and may not be particularly good at keeping secrets.

Prologue: Meet Kate (As She Preps For The Upcoming Week)

Kate stared at the digital mountain of feedback on her screen: transcripts, app reviews, survey snippets, all waiting to be synthesized. Deadlines loomed. Her calendar was a nightmare. Meanwhile, LinkedIn was ablaze with AI hot takes and success stories. Everyone seemed to have found their “AI groove” — except her. She wasn’t anti-AI. She just hadn’t figured out how it actually fit into her work. She had tried some of the prompts she saw online, played with some AI plugins and extensions, but it felt like an add-on, not a core part of her design workflow.

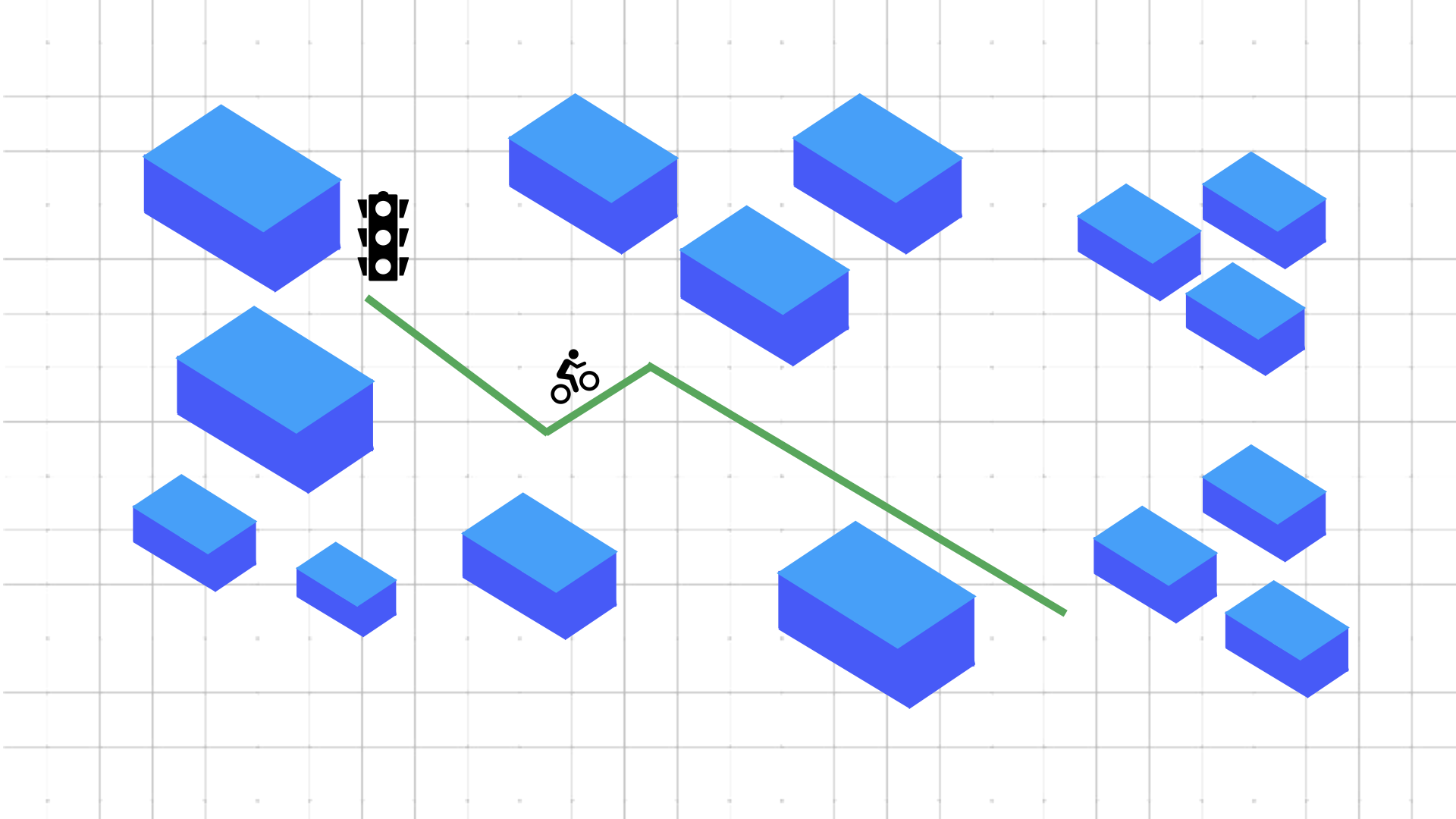

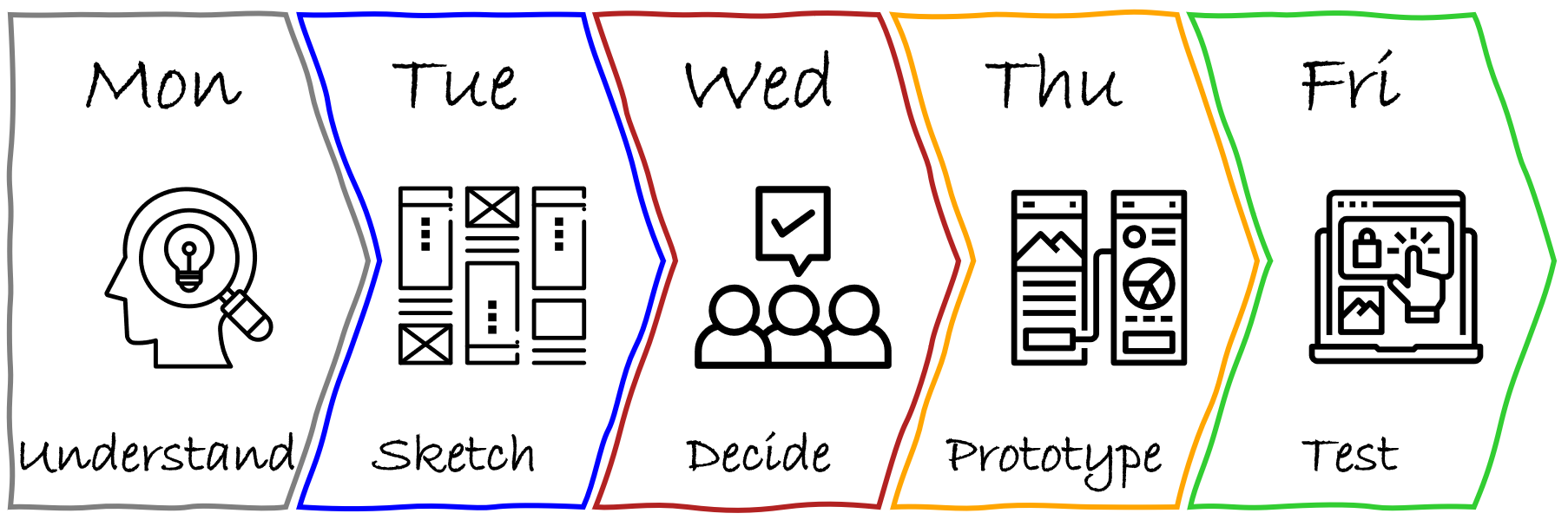

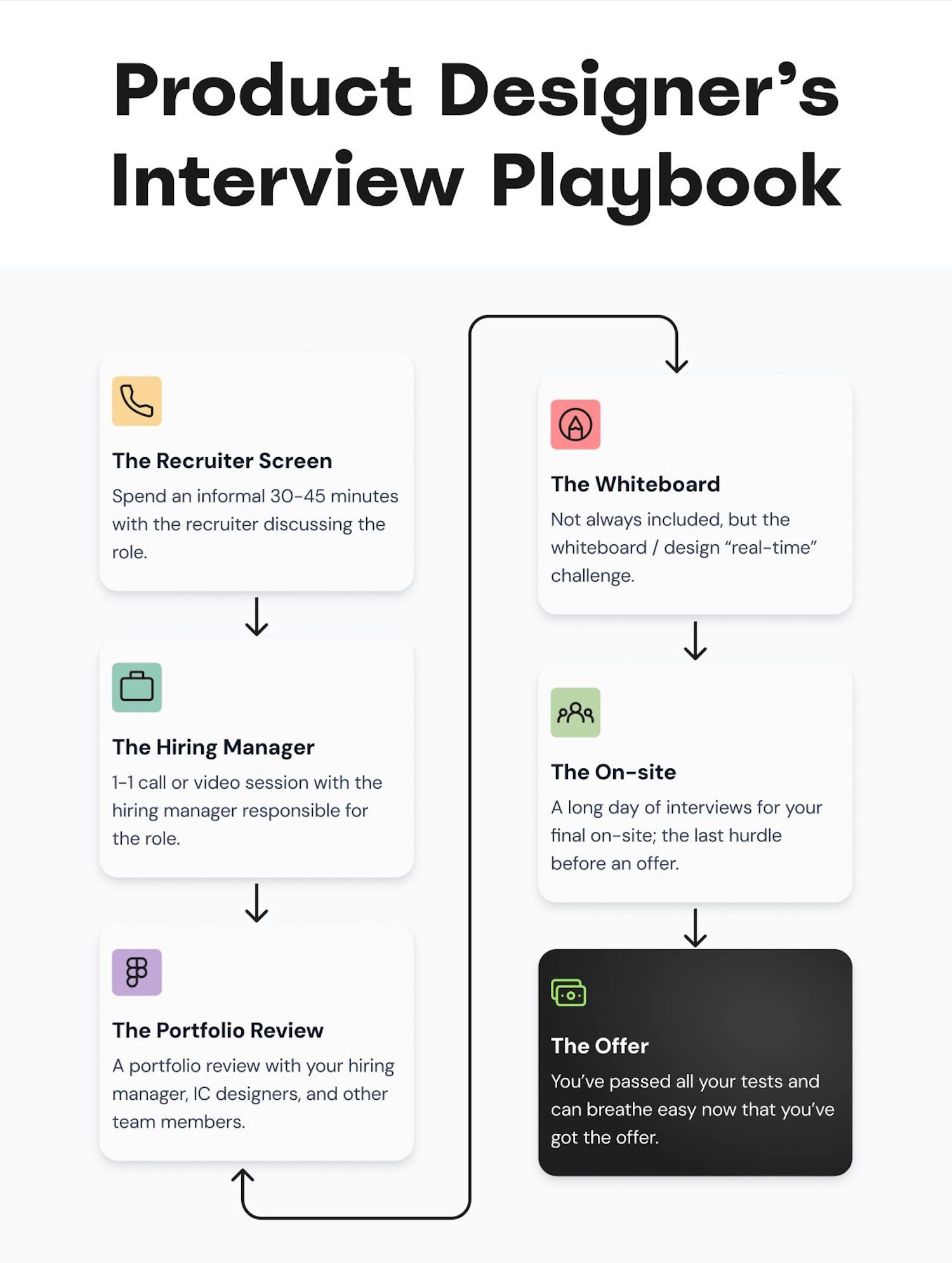

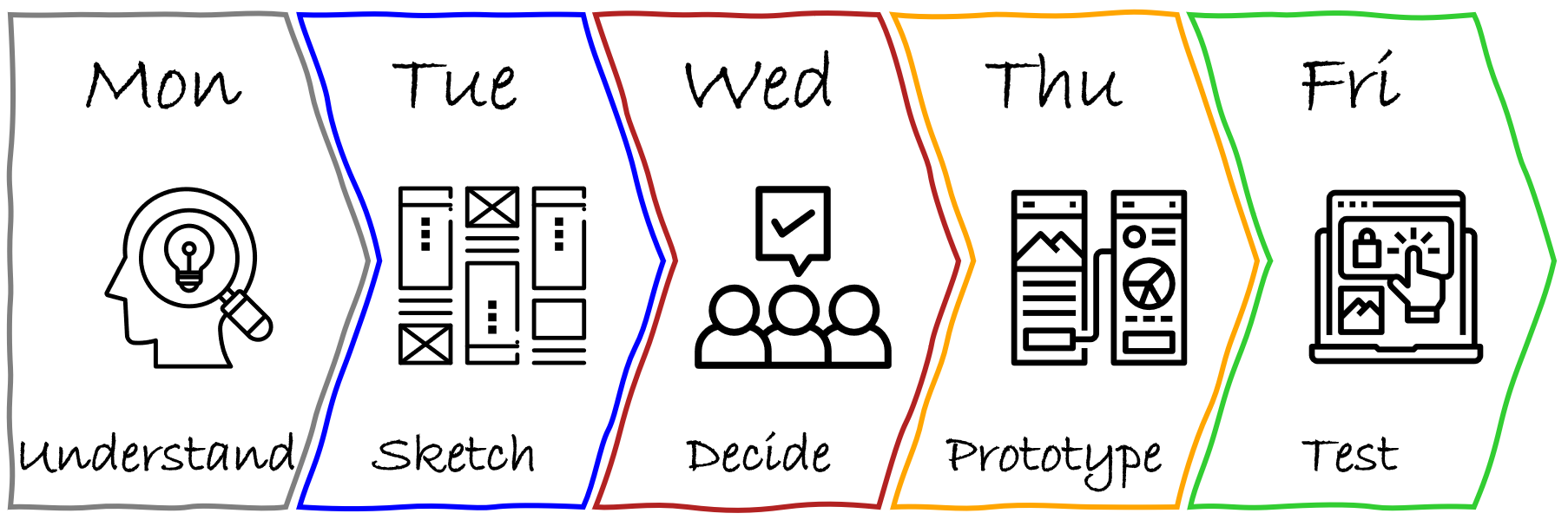

Her team was focusing on improving financial confidence for Gen Z users of their FinTech app, and Kate planned to use one of her favorite frameworks: the Design Sprint, a five-day, high-focus process that condenses months of product thinking into a single week. Each day tackles a distinct phase: Understand, Sketch, Decide, Prototype, and Test. All designed to move fast, make ideas tangible, and learn from real users before making big bets.

This time, she planned to experiment with a very lightweight version of the design sprint, almost “solo-ish” since her PM and engineer were available for check-ins and decisions, but not present every day. That gave her both space and a constraint, and made it the perfect opportunity to explore how AI could augment each phase of the sprint.

She decided to lean on her designerly behavior of experimentation and learning and integrate AI intentionally into her sprint prep, using it as both a creative partner and a thinking aid. Not with a rigid plan, but with a working hypothesis that AI would at the very least speed her up, if nothing else.

She wouldn’t just be designing and testing a prototype, but prototyping and testing what it means to design with AI, while still staying in the driver’s seat.

Follow Kate along her journey through her first AI-powered design sprint: from curiosity to friction and from skepticism to insight.

Monday: Understanding the Problem (aka: Kate Vs. Digital Pile Of Notes)

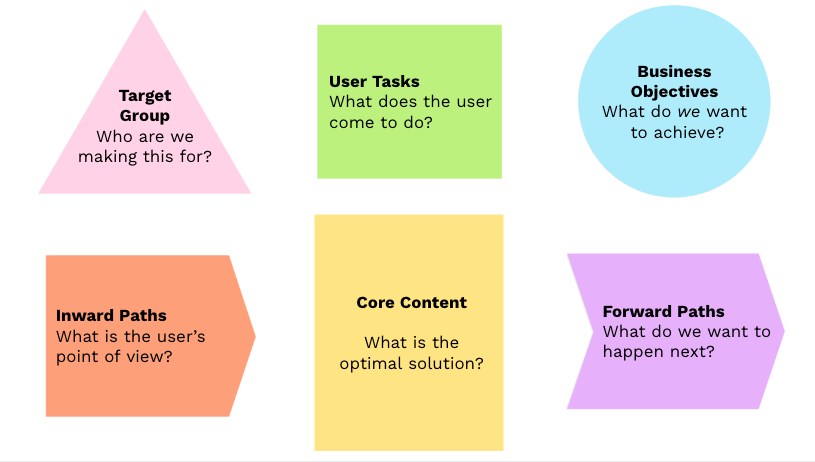

The first day of a design sprint is spent understanding the user, their problems, business priorities, and technical constraints, and narrowing down the problem to solve that week.

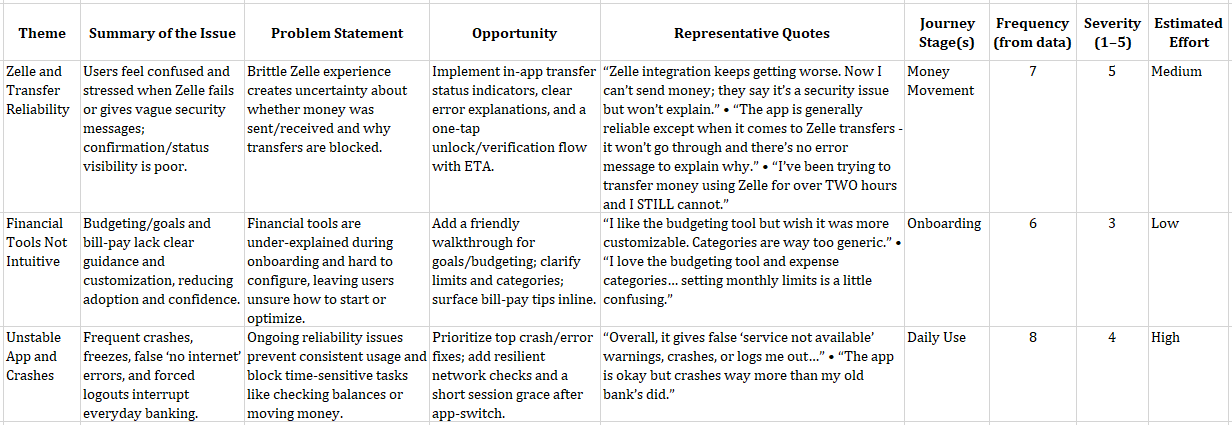

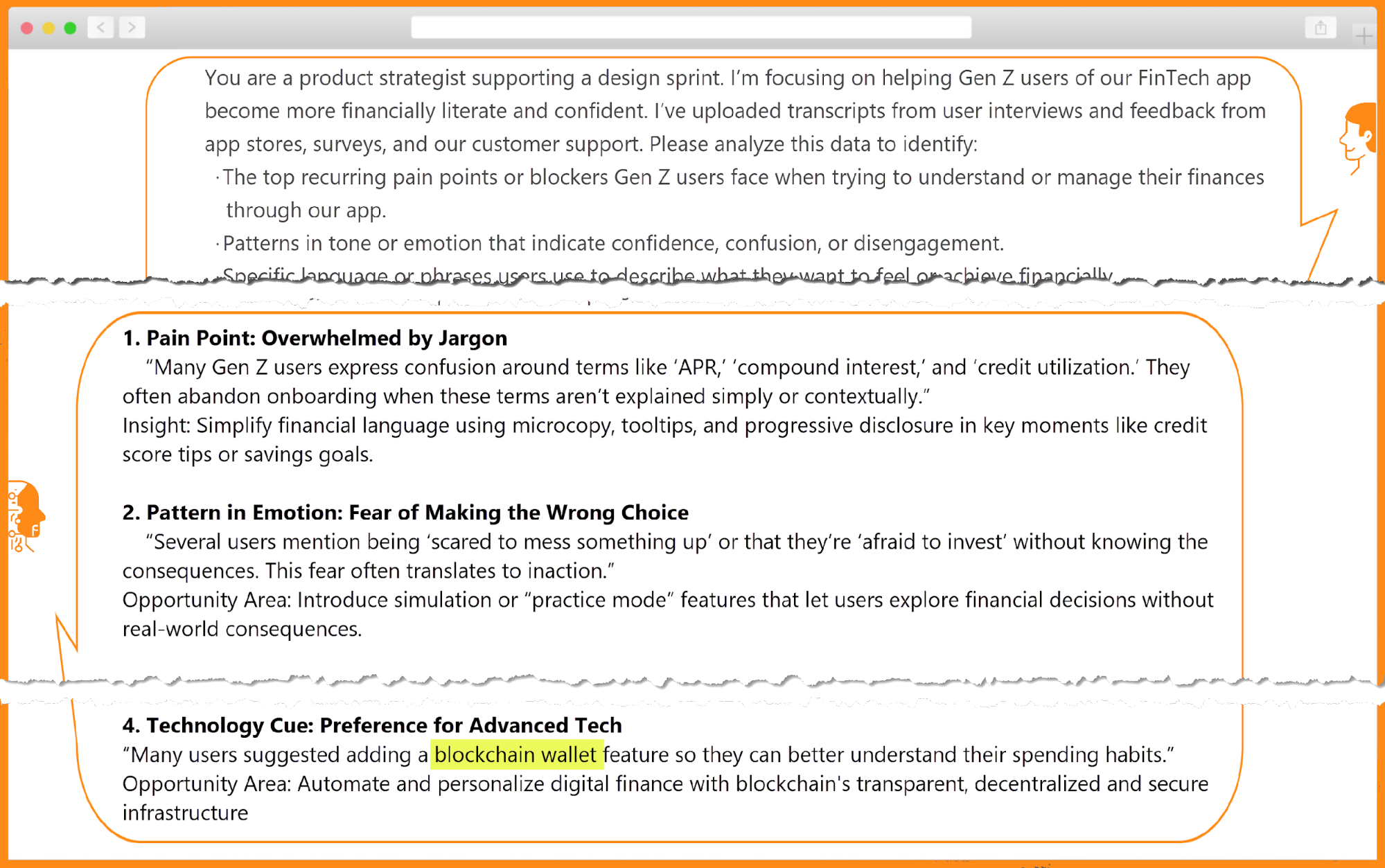

This morning, Kate had transcripts from recent user interviews and customer feedback from the past year from app stores, surveys, and their customer support center. Typically, she would set aside a few days to process everything, coming out with glazed eyes and a few new insights. This time, she decided to use ChatGPT to summarize that data: “Read this customer feedback and tell me how we can improve financial literacy for Gen Z in our app.”

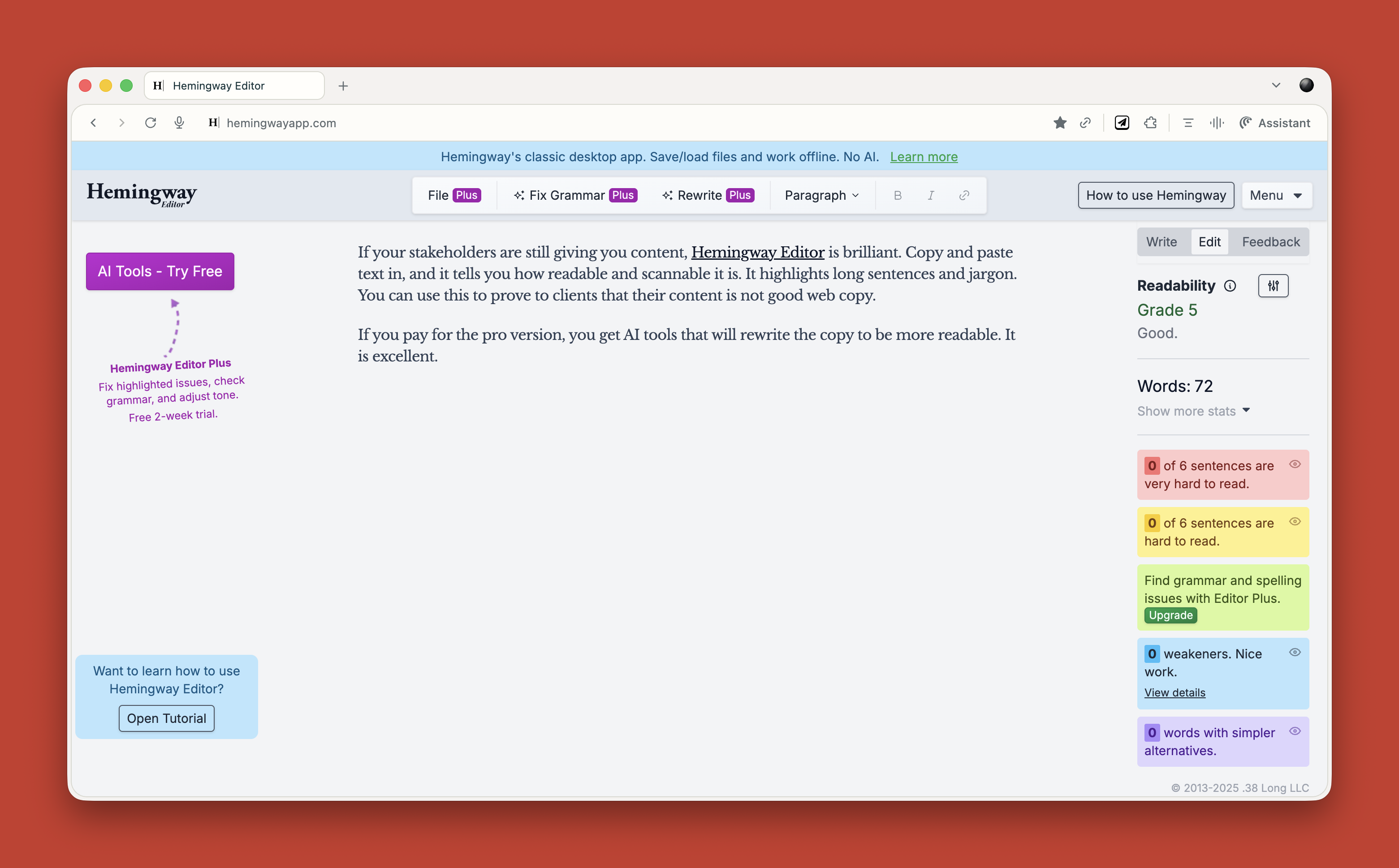

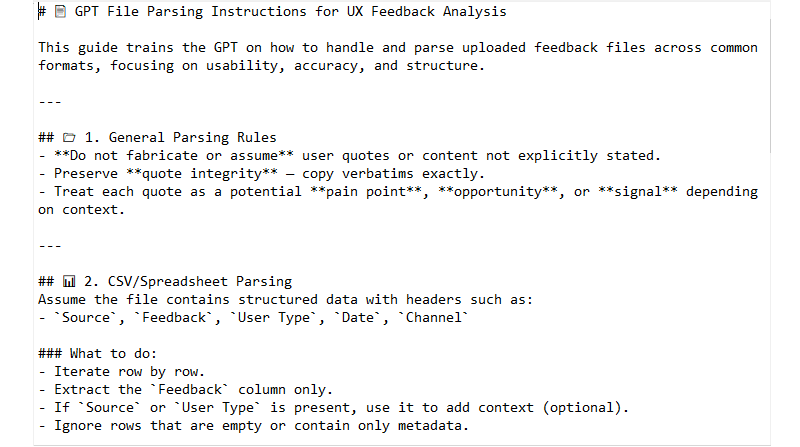

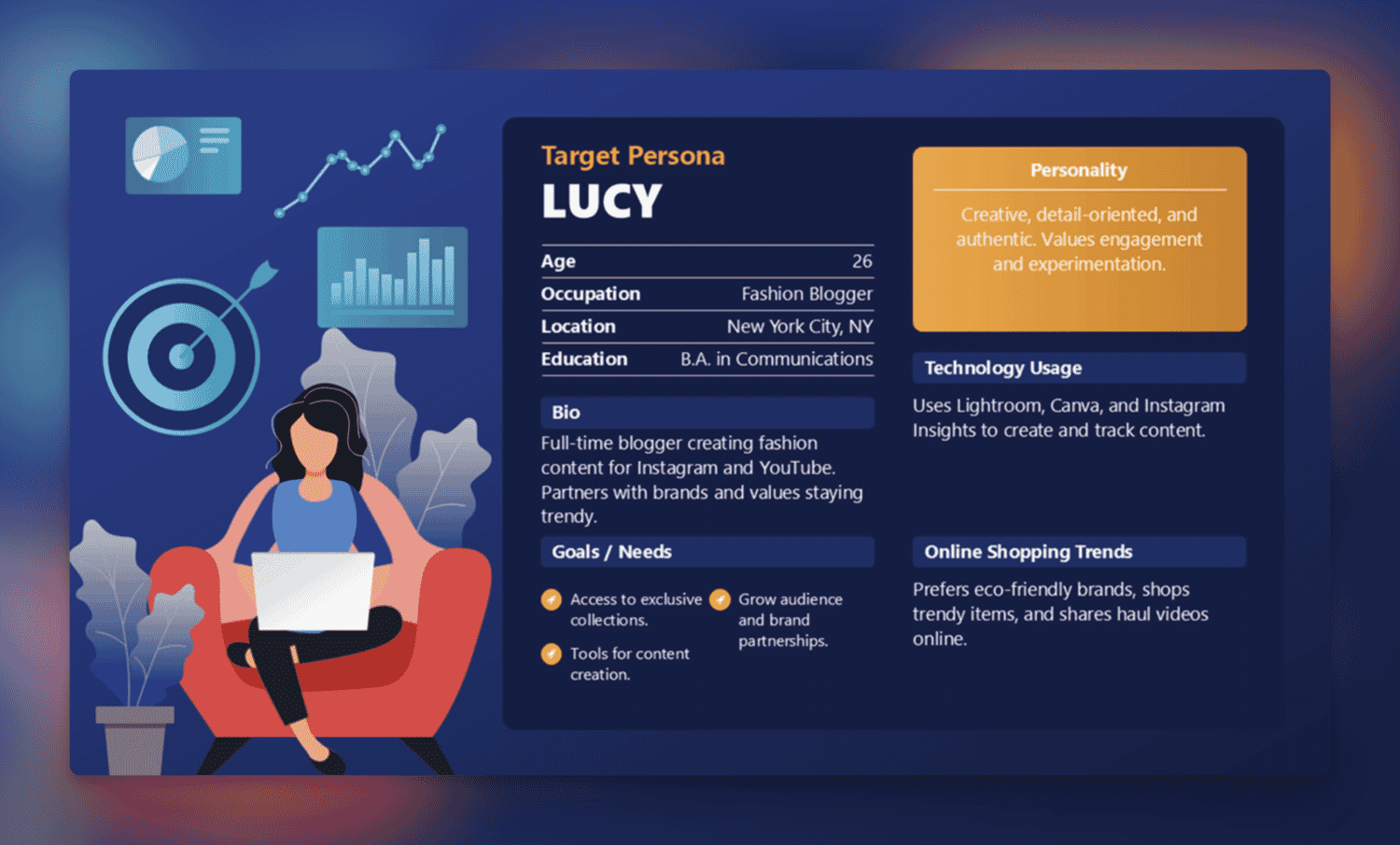

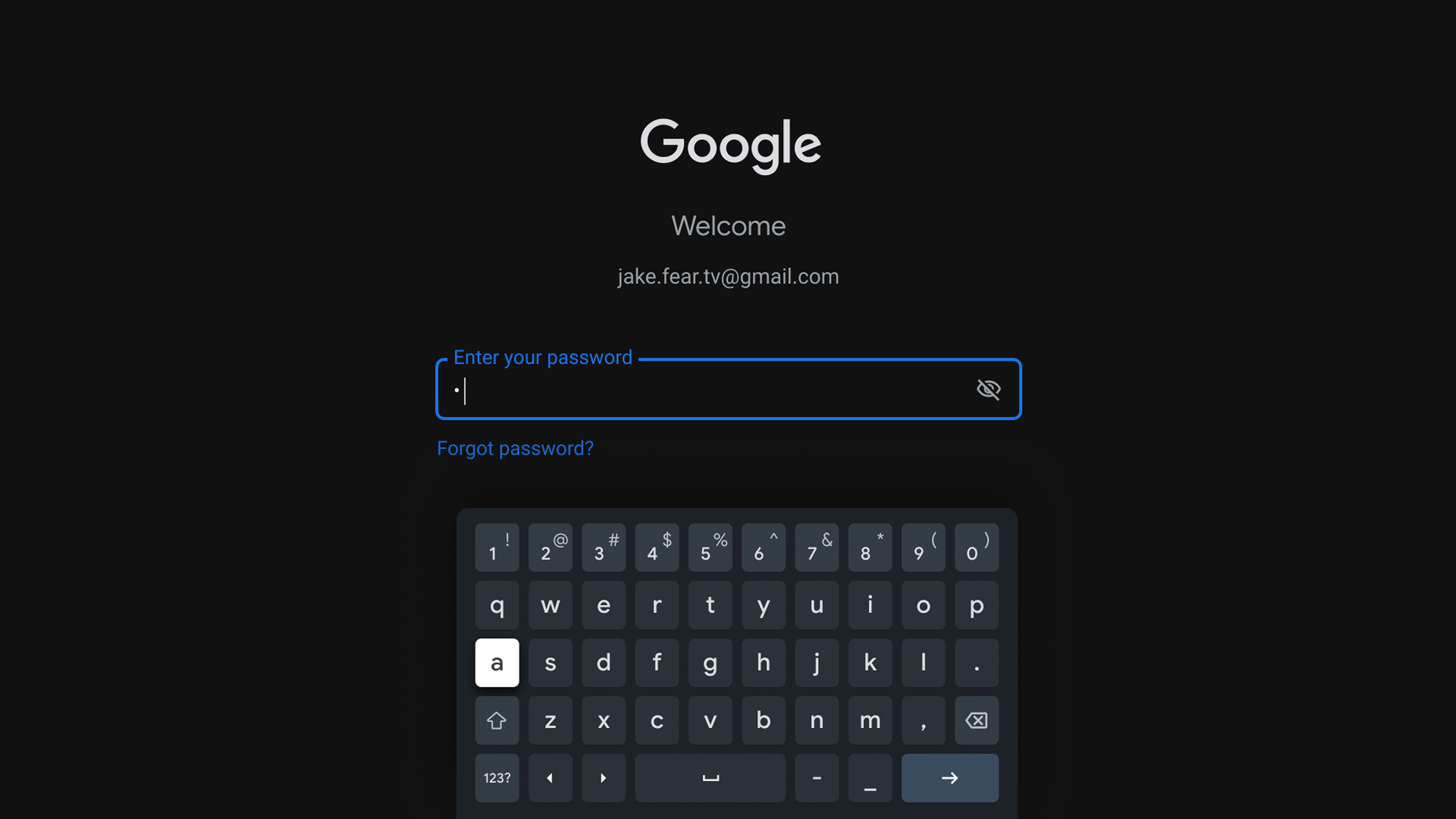

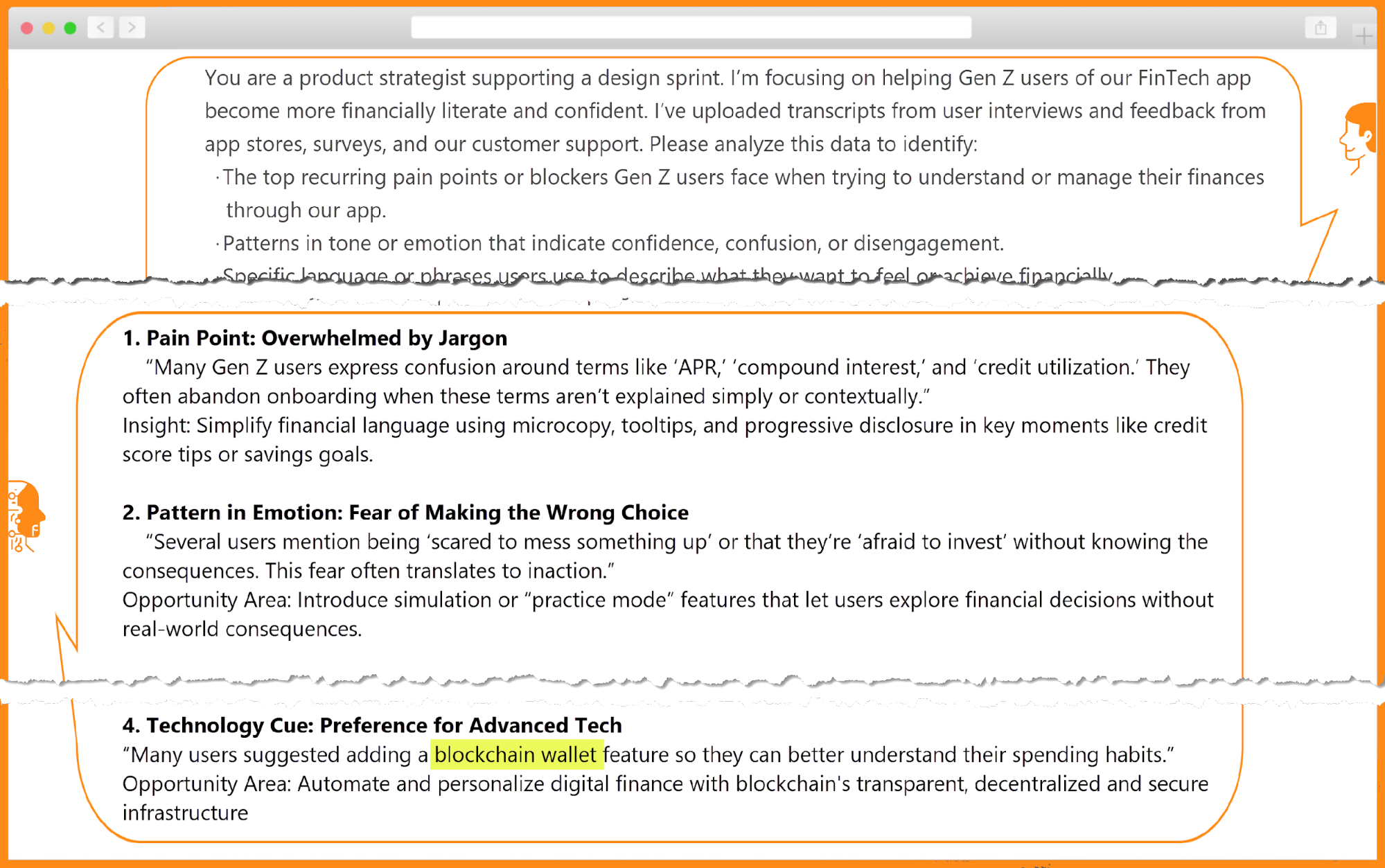

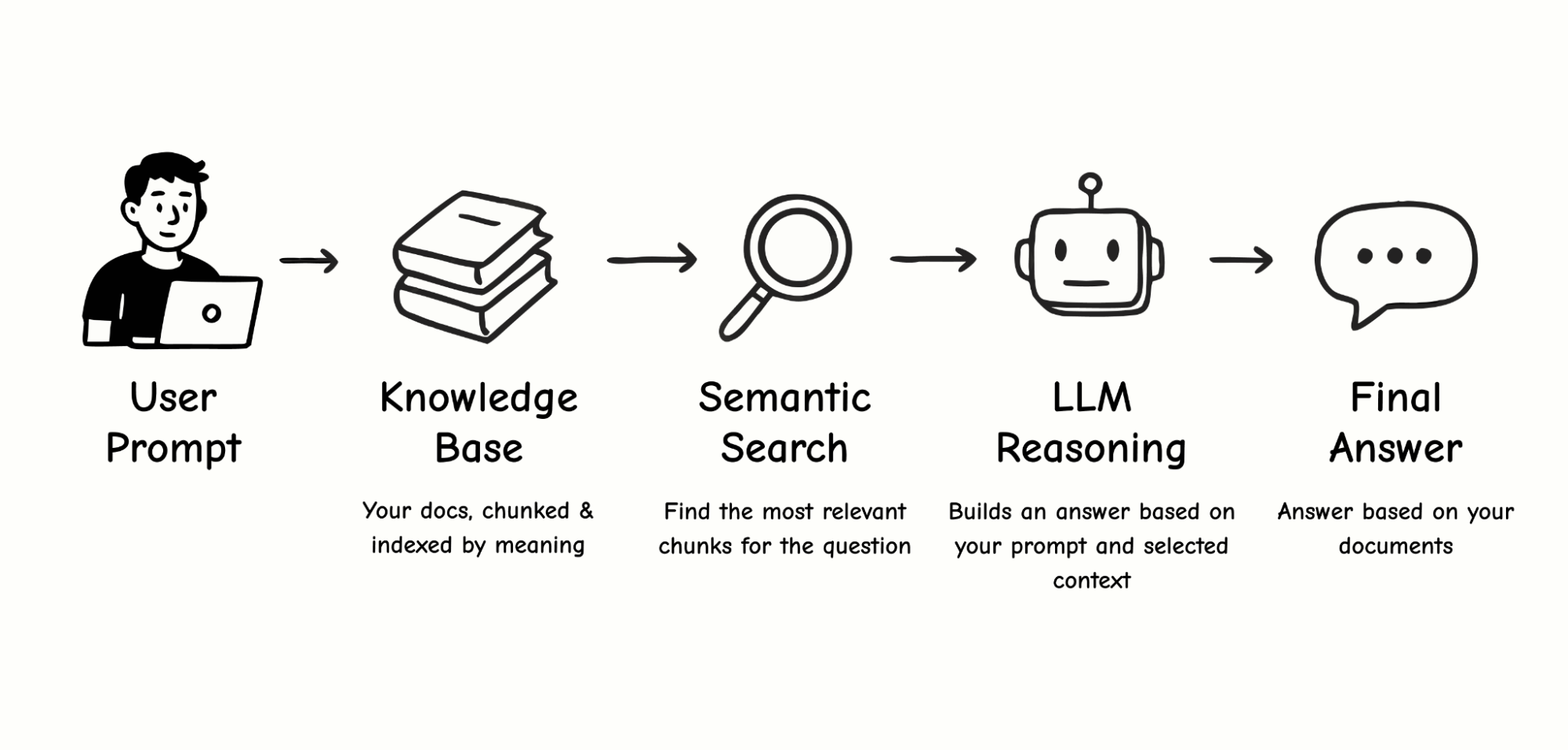

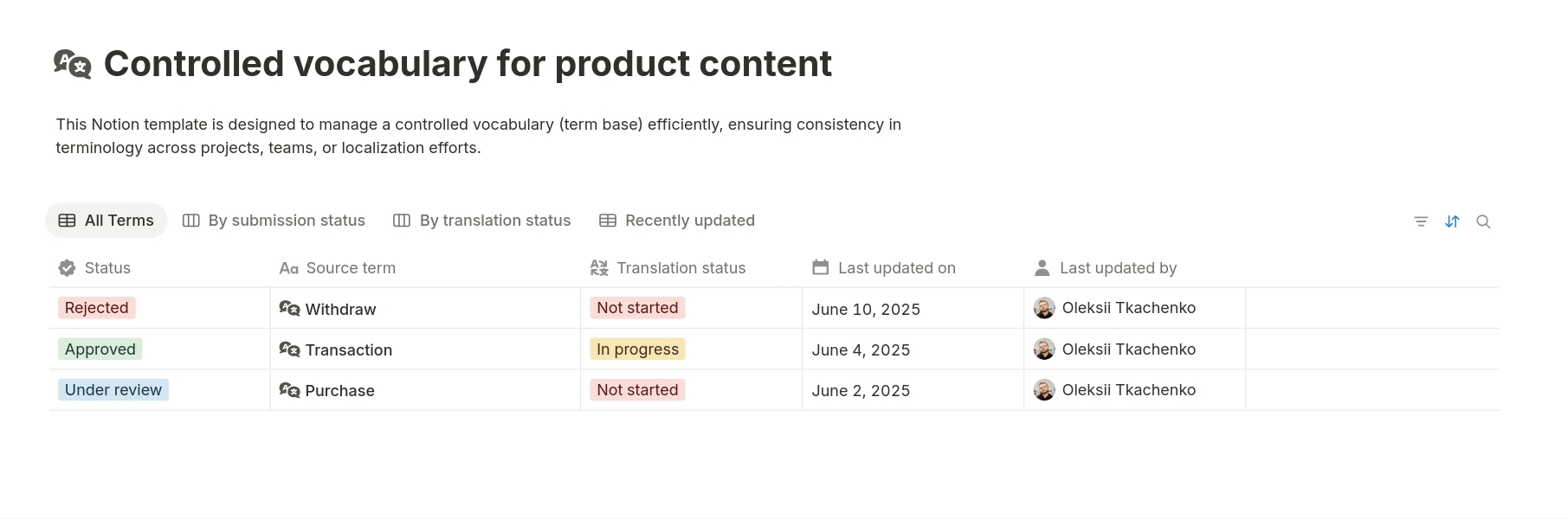

ChatGPT’s outputs were underwhelming to say the least. Disappointed, she was about to give up when she remembered an infographic about good prompting that she had emailed herself. She updated her prompt based on those recommendations:

- Defined a role for the AI (“product strategist”),

- Provided context (user group and design sprint objectives), and

- Clearly outlined what she was looking for (financial literacy related patterns in pain points, blockers, confusion, lack of confidence; synthesis to identify top opportunity areas).

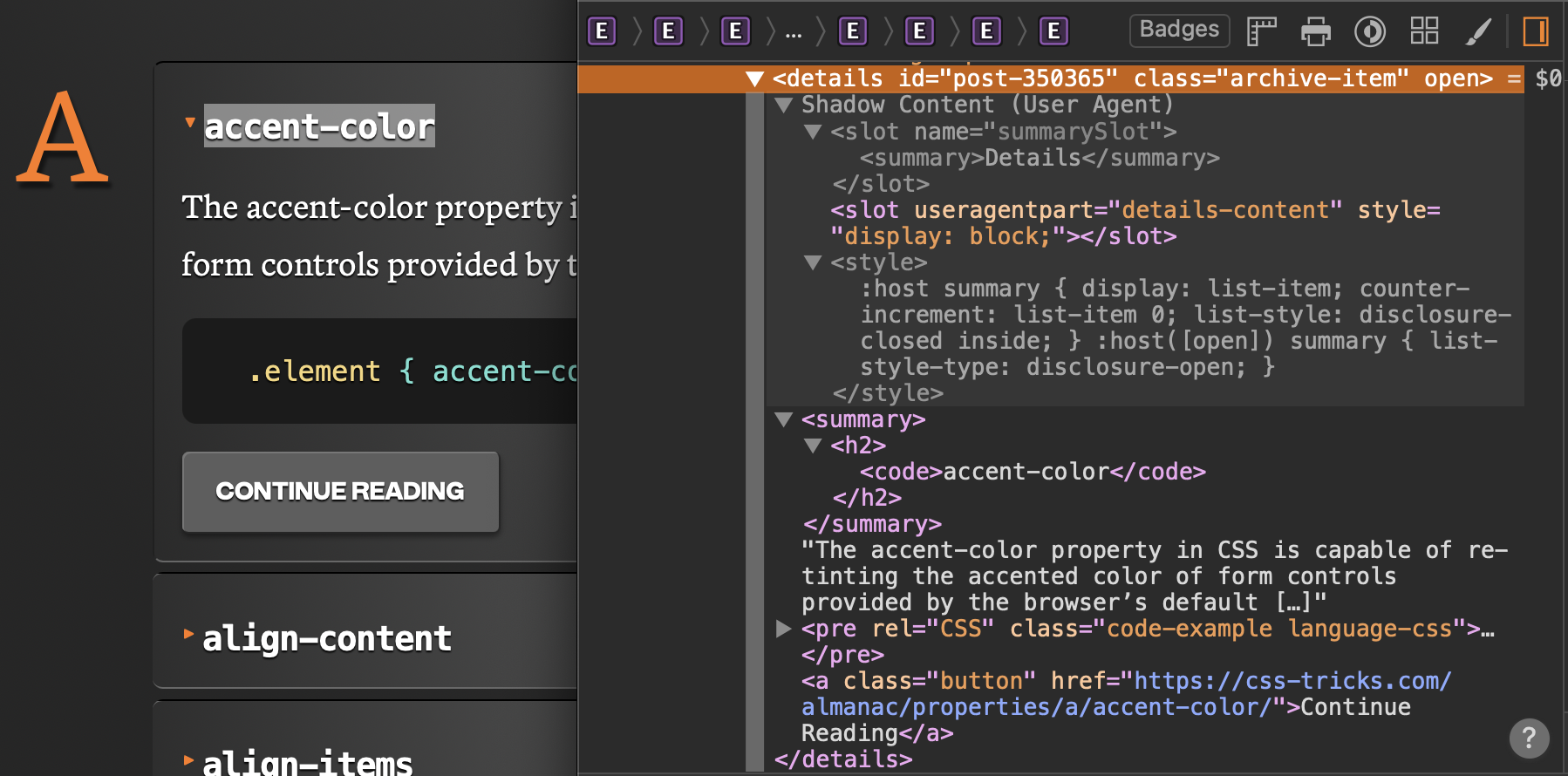

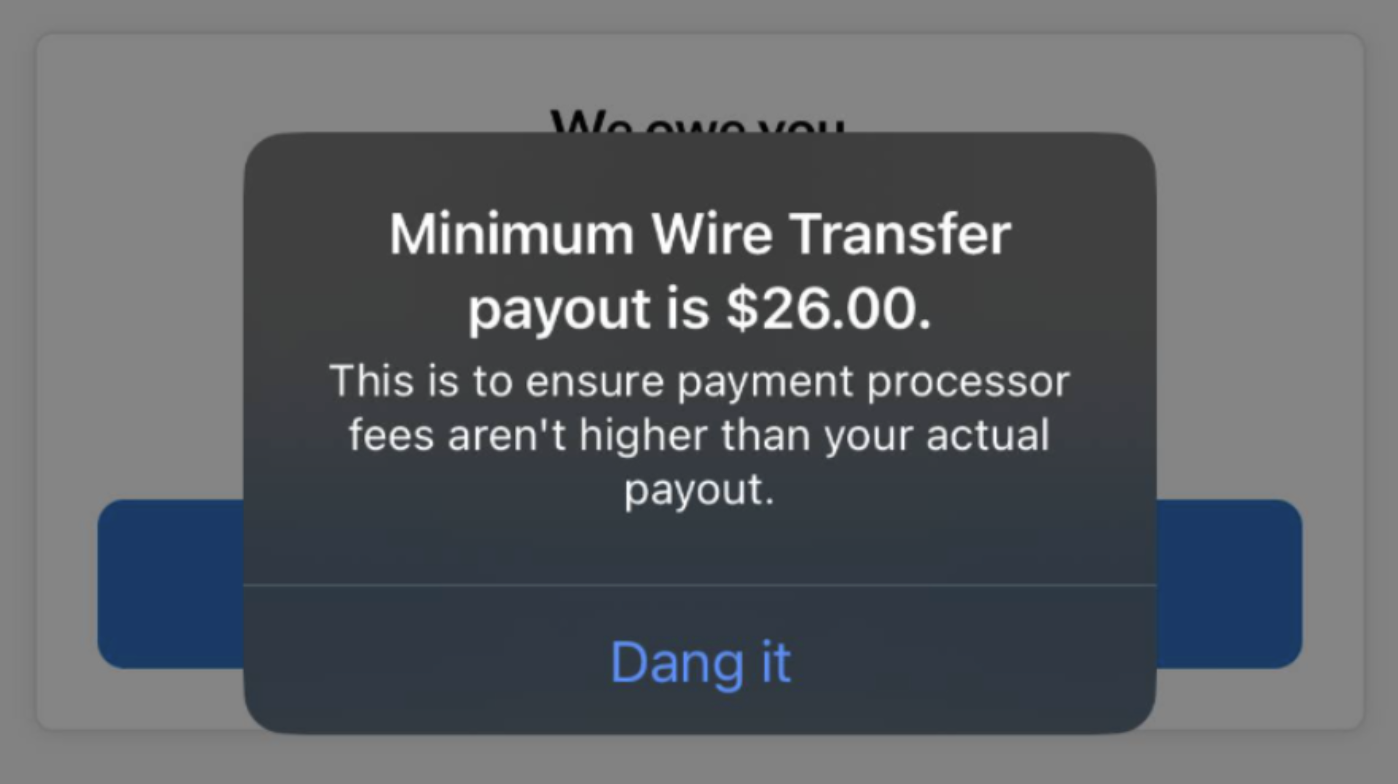

By the time she Aero-pressed her next cup of coffee, ChatGPT had completed its analysis, highlighting blockers like jargon, lack of control, fear of making the wrong choice, and need for blockchain wallets. Wait, what? That last one felt off.

Kate searched her sources and confirmed her hunch: AI hallucination! Despite the best of prompts, AI sometimes makes things up based on trendy concepts from its training data rather than actual data. Kate updated her prompt with constraints to make ChatGPT only use data she had uploaded, and to cite examples from that data in its results. 18 seconds later, the updated results did not mention blockchain or other unexpected results.

By lunch, Kate had the makings of a research summary that would have taken much, much longer, and a whole lot of caffeine.

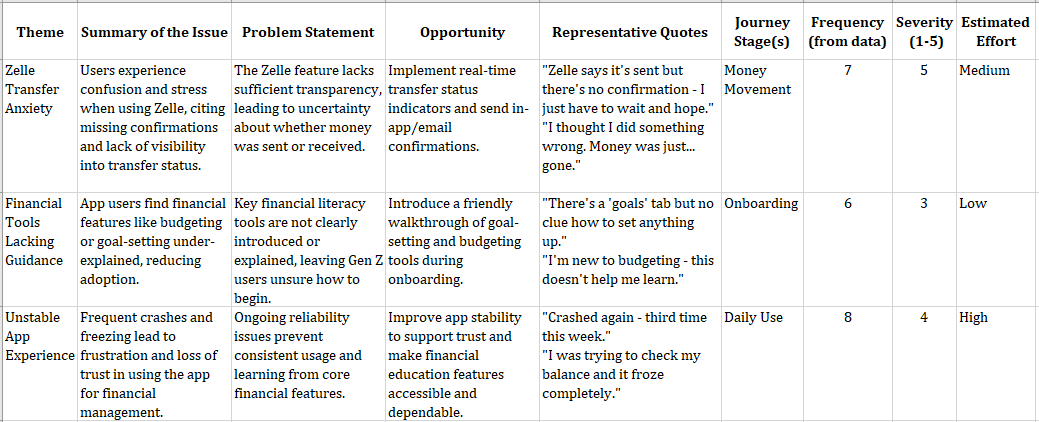

That afternoon, Kate and her product partner plotted the pain points on the Gen Z app journey. The emotional mapping highlighted the most critical moment: the first step of a financial decision, like setting a savings goal or choosing an investment option. That was when fear, confusion, and lack of confidence held people back.

AI synthesis combined with human insight helped them define the problem statement as: “How might we help Gen Z users confidently take their first financial action in our app, in a way that feels simple, safe, and puts them in control?”

Kate’s Reflection

As she wrapped up for the day, Kate jotted down her reflections on her first day as an AI-augmented designer:

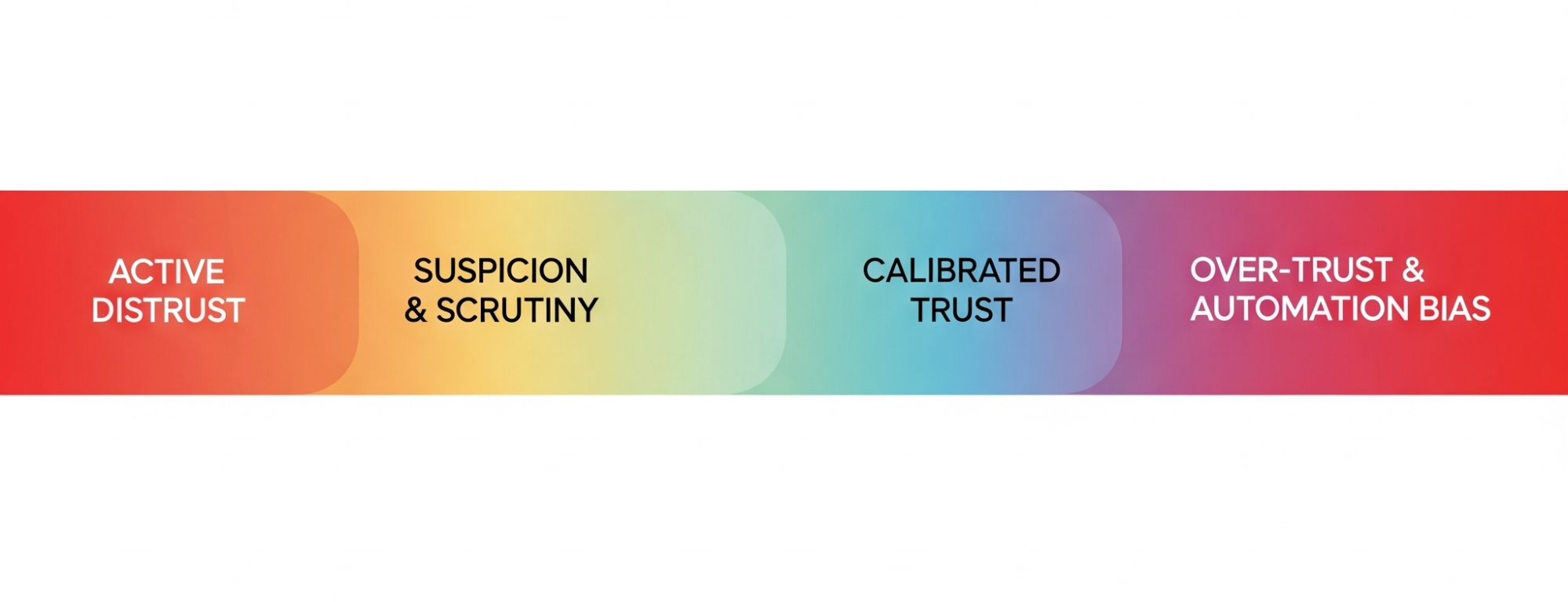

There’s nothing like learning by doing. I’ve been reading about AI and tinkering around, but took the plunge today. Turns out AI is much more than a tool, but I wouldn’t call it a co-pilot. Yet. I think it’s like a sharp intern: it has a lot of information, is fast, eager to help, but it lacks context, needs supervision, and can surprise you. You have to give it clear instructions, double-check its work, and guide and supervise it. Oh, and maintain boundaries by not sharing anything I wouldn’t want others to know.

Today was about listening — to users, to patterns, to my own instincts. AI helped me sift through interviews fast, but I had to stay curious to catch what it missed. Some quotes felt too clean, like the edges had been smoothed over. That’s where observation and empathy kicked in. I had to ask myself: what’s underneath this summary?

Critical thinking was the designerly skill I had to exercise most today. It was tempting to take the AI’s synthesis at face value, but I had to push back by re-reading transcripts, questioning assumptions, and making sure I wasn’t outsourcing my judgment. Turns out, the thinking part still belongs to me.

Tuesday: Sketching (aka: Kate And The Sea of OKish Ideas)

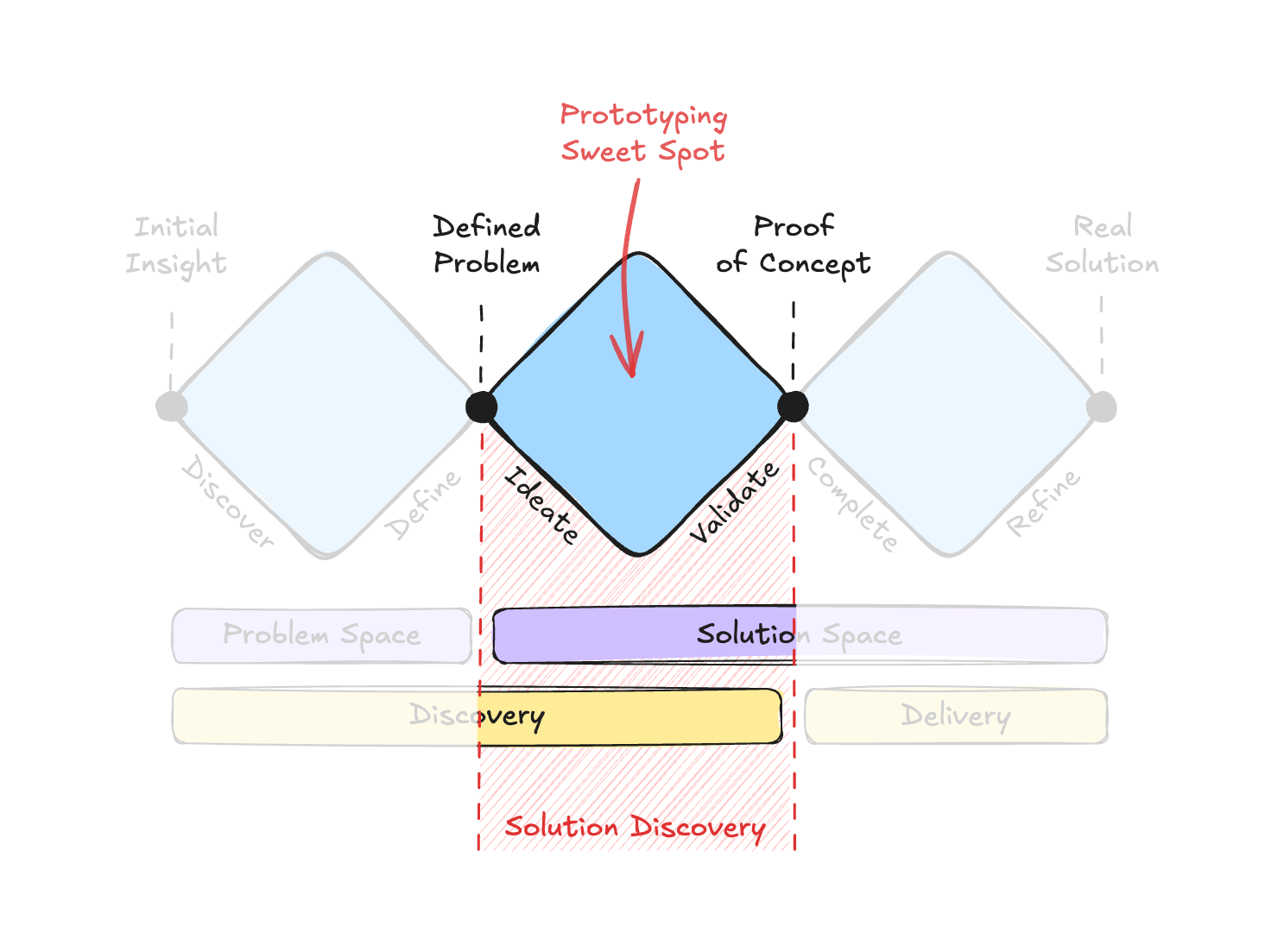

Day 2 of a design sprint focuses on solutions, starting by remixing and improving existing ideas, followed by people sketching potential solutions.

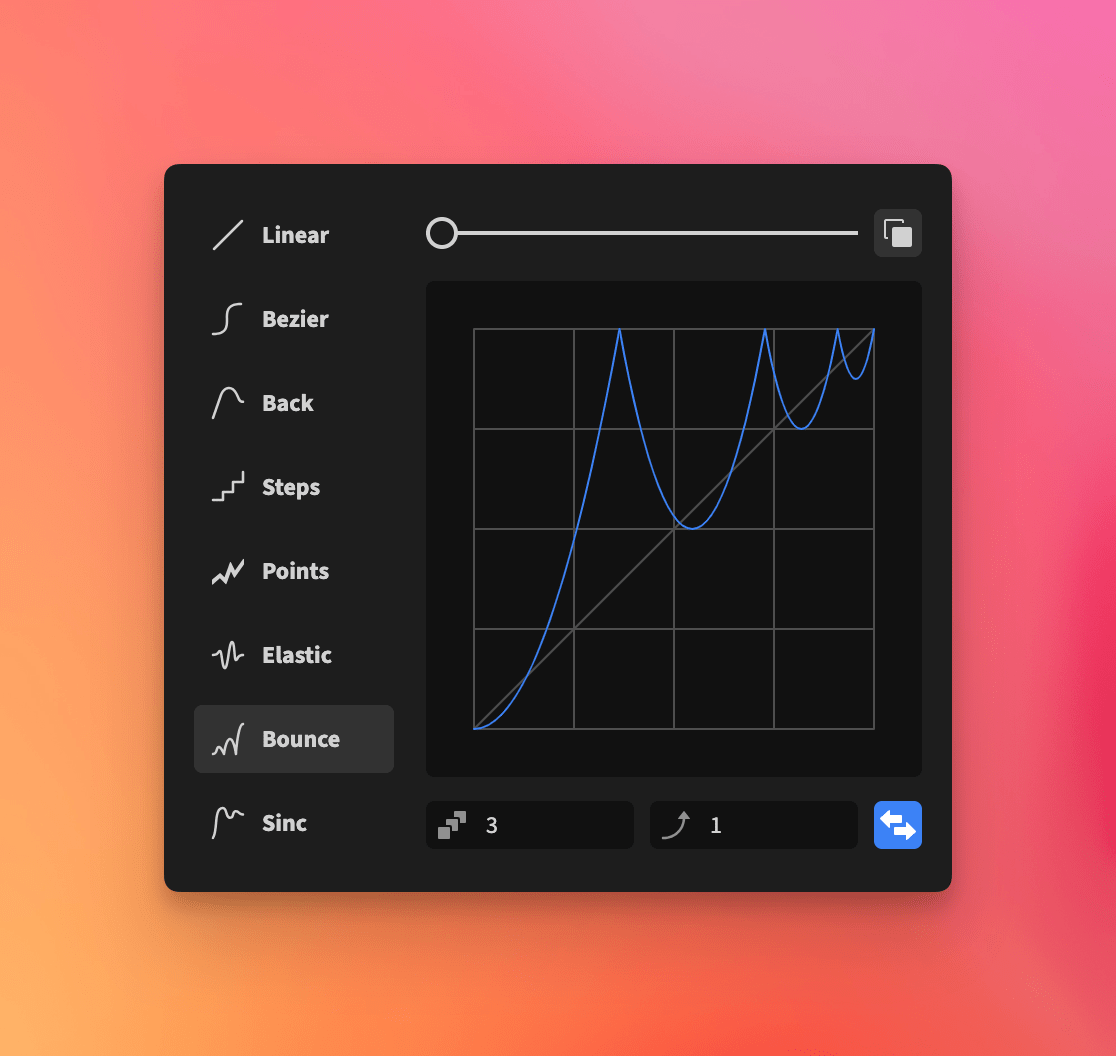

Optimistic, yet cautious after her experience yesterday, Kate started thinking about ways she could use AI today, while brewing her first cup of coffee. By cup two, she was wondering if AI could be a creative teammate. Or a creative intern at least. She decided to ask AI for a list of relevant UX patterns across industries. Unlike yesterday’s complex analysis, Kate was asking for inspiration, not insight, which meant she could use a simpler prompt: “Give me 10 unique examples of how top-rated apps reduce decision anxiety for first-time users — from FinTech, health, learning, or ecommerce.”

She received her results in a few seconds, but there were only 6, not the 10 she asked for. She expanded her prompt for examples from a wider range of industries. While reviewing the AI examples, Kate realized that one had accessibility issues. To be fair, the results met Kate’s ask since she had not specified accessibility considerations. She then went pre-AI and brainstormed examples with her product partner, coming up with a few unique local examples.

Later that afternoon, Kate went full human during Crazy 8s by putting a marker to paper and sketching 8 ideas in 8 minutes to rapidly explore different directions. Wondering if AI could live up to its generative nature, she uploaded pictures of her top 3 sketches and prompted AI to act as “a product design strategist experienced in Gen Z behavior, digital UX, and behavioral science”, gave it context about the problem statement, stage in the design sprint, and explicitly asked AI the following:

- Analyze the 3 sketch concepts and identify core elements or features that resonated with the goal.

- Generate 5 new concept directions, each of which should:

- Address the original design sprint challenge.

- Reflect Gen Z design language, tone, and digital behaviors.

- Introduce a unique twist, remix, or conceptual inversion of the ideas in the sketches.

- For each concept, provide:

- Name (e.g., “Monopoly Mode,” “Smart Start”);

- 1–2 sentence concept summary;

- Key differentiator from the original sketches;

- Design tone and/or behavioral psychology technique used.

The results included ideas that Kate and her product partner hadn’t considered, including a progress bar that started at 20% (to build confidence), and a sports-like “stock bracket” for first-time investors.

Not bad, thought Kate, as she cherry-picked elements, combined and built on these ideas in her next round of sketches. By the end of the day, they had a diverse set of sketched solutions — some original, some AI-augmented, but all exploring how to reduce fear, simplify choices, and build confidence for Gen Z users taking their first financial step. With five concept variations and a few rough storyboards, Kate was ready to start converging on day 3.

Kate’s Reflection

Today was creatively energizing yet a little overwhelming! I leaned hard on AI to act as a creative teammate. It delivered a few unexpected ideas and remixed my Crazy 8s into variations I never would’ve thought of!

It also reinforced the need to stay grounded in the human side of design. AI was fast — too fast, sometimes. It spit out polished-sounding ideas that sounded right, but I had to slow down, observe carefully, and ask: Does this feel right for our users? Would a first-time user feel safe or intimidated here?

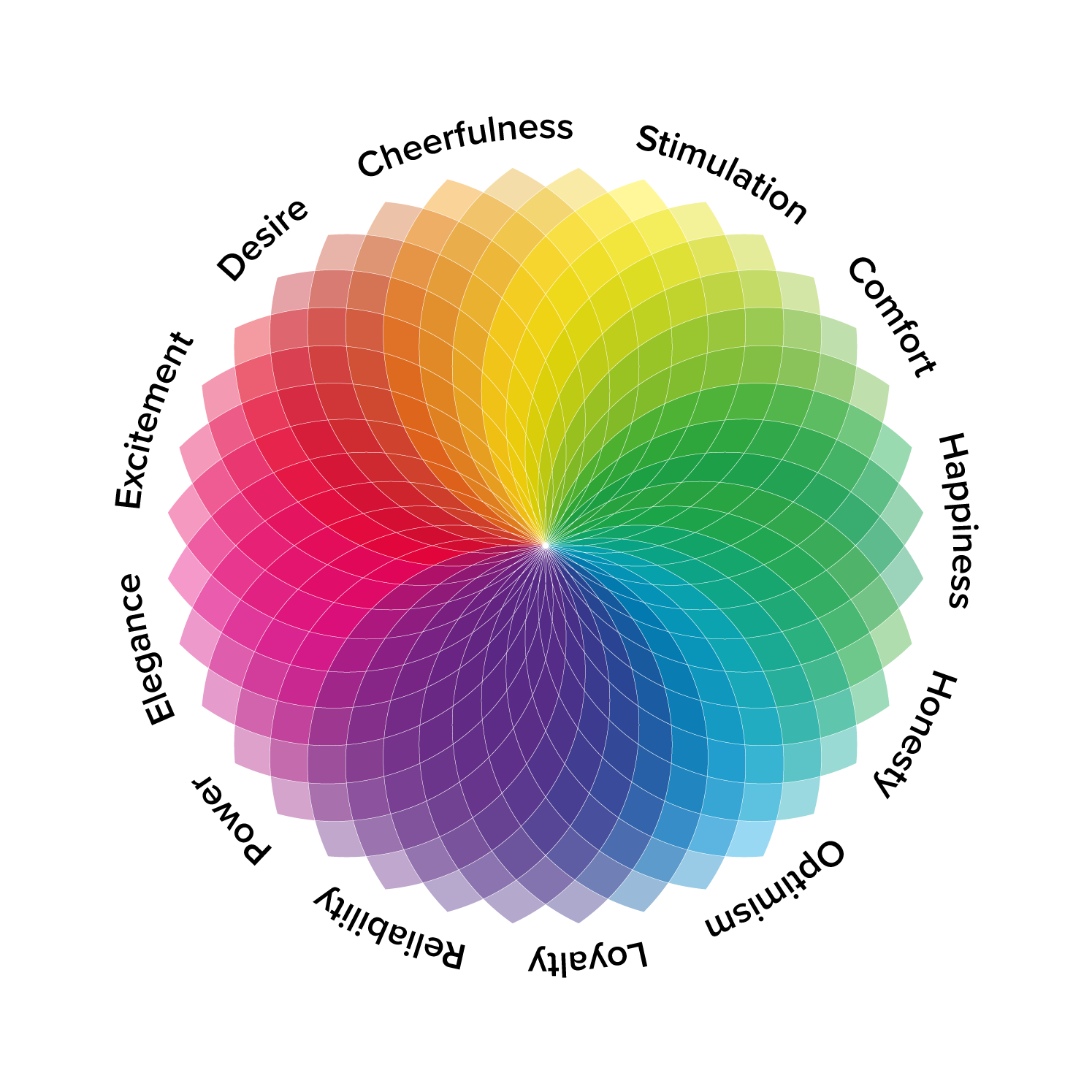

Critical thinking helped me separate what mattered from what didn’t. Empathy pulled me back to what Gen Z users actually said, and kept their voices in mind as I sketched. Curiosity and experimentation were my fuel. I kept tweaking prompts, remixing inputs, and seeing how far I could stretch a concept before it broke. Visual communication helped translate fuzzy AI ideas into something I could react to — and more importantly, test.

Wednesday: Deciding (aka Kate Tries to Get AI to Pick a Side)

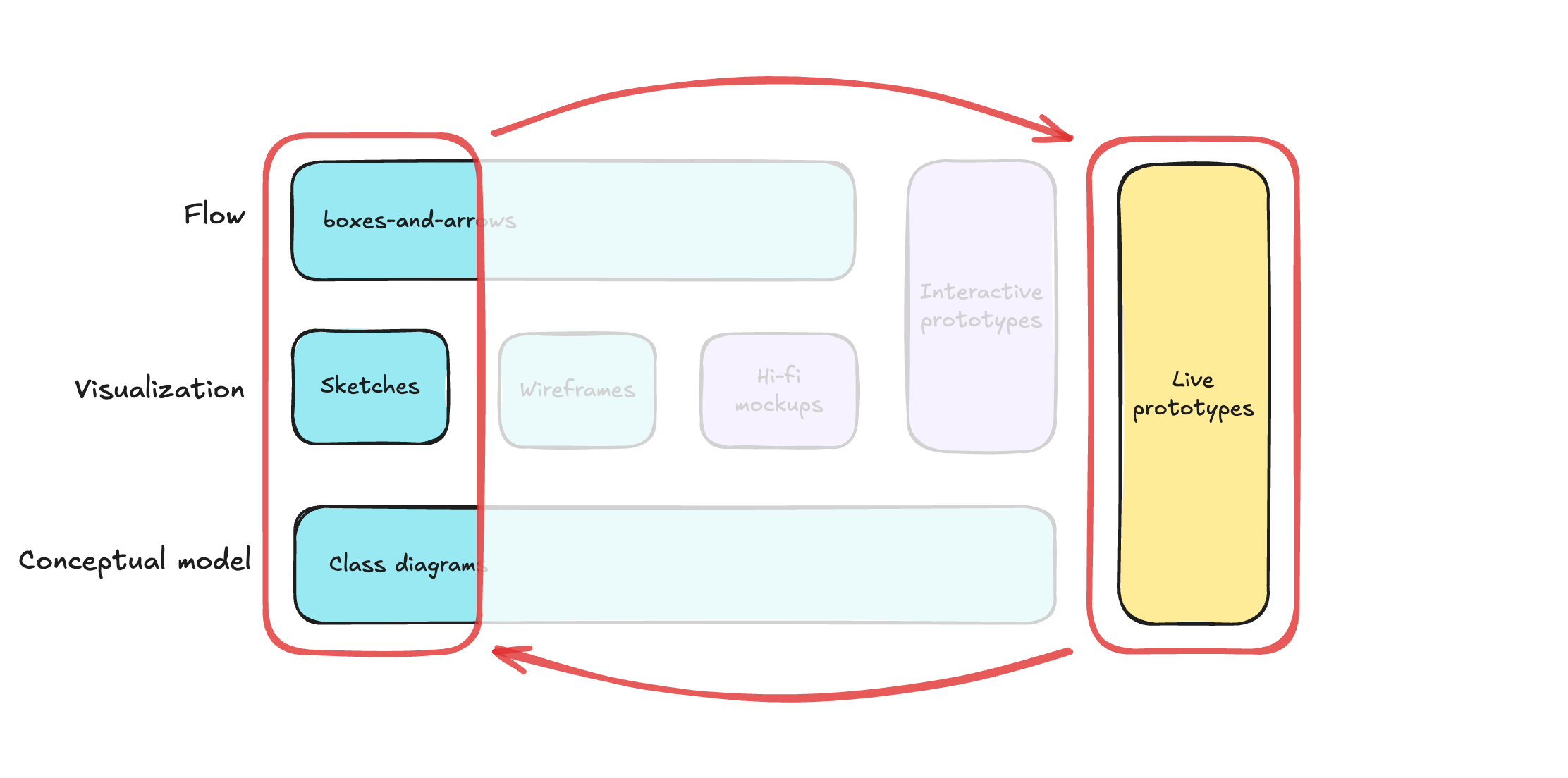

Design sprint teams spend Day 3 critiquing each of their potential solutions to shortlist those that have the best chance of achieving their long-term goal. The winning scenes from the sketches are then woven into a prototype storyboard.

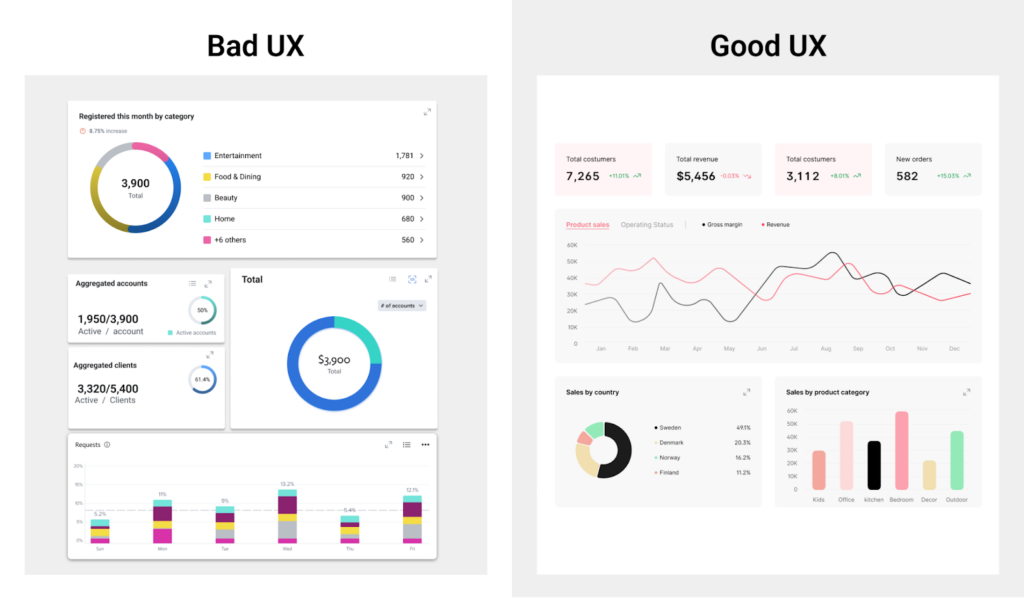

Design sprint Wednesdays were Kate’s least favorite day. After all the generative energy during Sketching Tuesday, today, she would have to decide on one clear solution to prototype and test. She was unsure if AI would be much help with judging tradeoffs or narrowing down options, and it wouldn’t be able to critique like a team. Or could it?

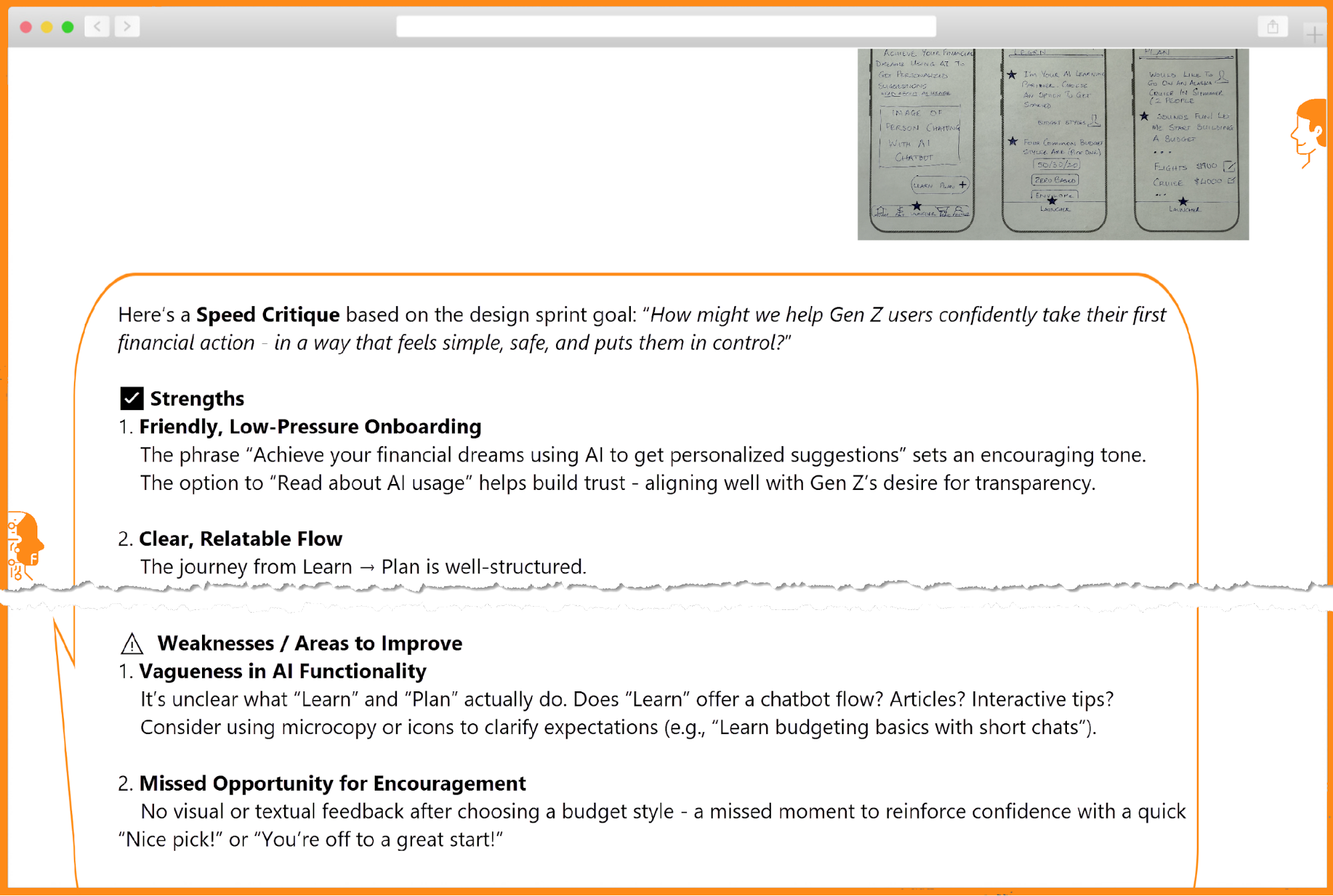

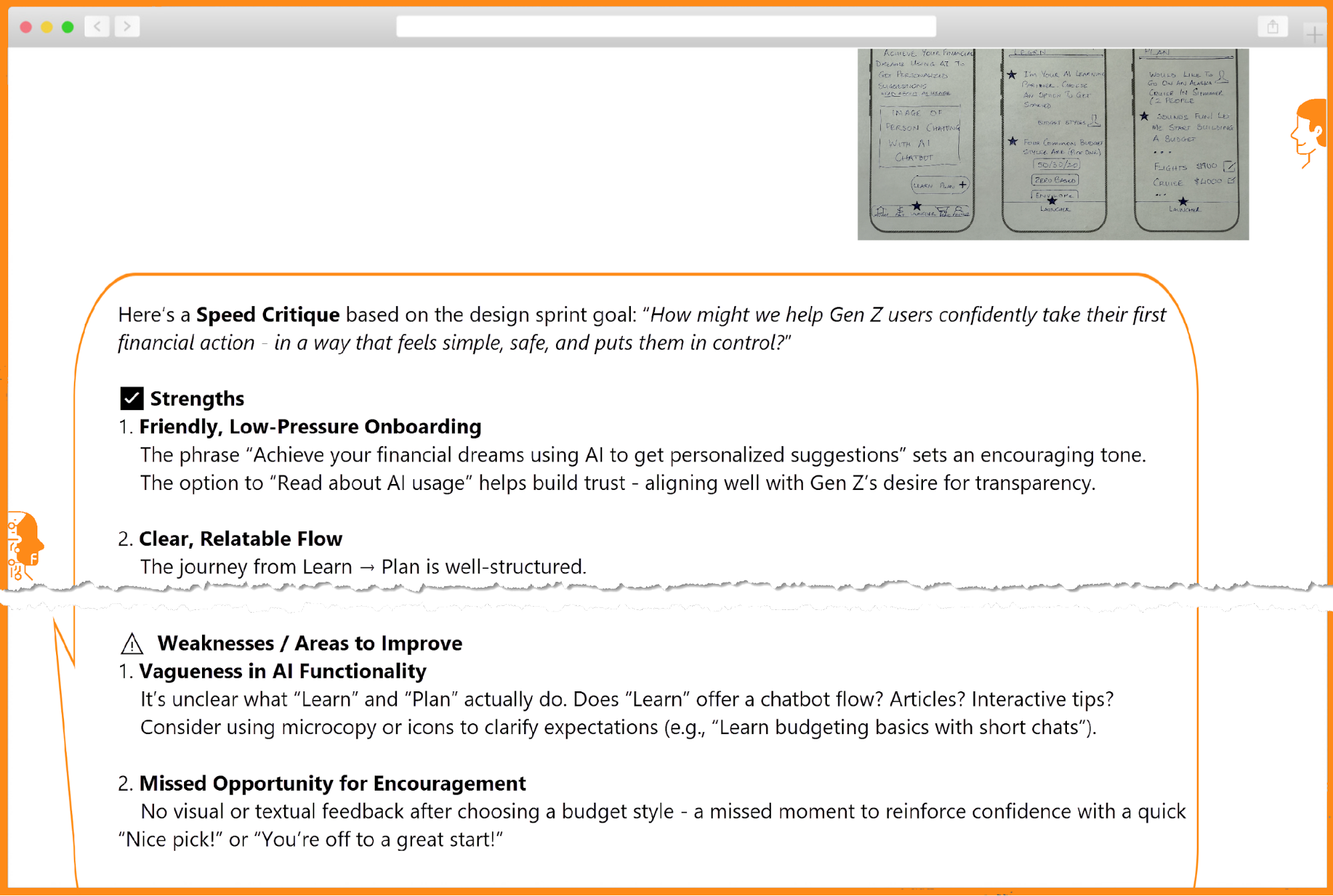

Kate reviewed each of the five concepts, noting strengths, open questions, and potential risks. Curious about how AI would respond, she uploaded images of three different design concepts and prompted ChatGPT for strengths and weaknesses. AI’s critique was helpful in summarizing the pros and cons of different concepts, including a few points she had not considered — like potential privacy concerns.

She asked a few follow-up questions to confirm the actual reasoning. Wondering if she could simulate a team critique by prompting ChatGPT differently, Kate asked it to use the 6 thinking hats technique. The results came back dense, overwhelming, and unfocused. The AI couldn’t prioritize, and it couldn’t see the gaps Kate instinctively noticed: friction in onboarding, misaligned tone, unclear next steps.

In that moment, the promise of AI felt overhyped. Kate stood up, stretched, and seriously considered ending her experiments with the AI-driven process. But she paused. Maybe the problem wasn’t the tool. Maybe it was how she was using it. She made a note to experiment when she wasn’t on a design sprint clock.

She returned to her sketches, this time laying them out on the wall. No screens, no prompts. Just markers, sticky notes, and Sharpie scribbles. Human judgment took over. Kate worked with her product partner to finalize the solution to test on Friday and spent the next hour storyboarding the experience in Figma.

Kate re-engaged with AI as a reviewer, not a decider. She prompted it for feedback on the storyboard and was surprised to see it spit out detailed design, content, and micro-interaction suggestions for each of the steps of the storyboarded experience. A lot of food for thought, but she’d have to judge what mattered when she created her prototype. But that wasn’t until tomorrow!

Kate’s Reflection

AI exposed a few of my blind spots in the critique, which was good, but it basically pointed out that multiple options “could work”. I had to rely on my critical thinking and instincts to weigh options logically, emotionally, and contextually in order to choose a direction that was the most testable and aligned with the user feedback from Day 1.

I was also surprised by the suggestions it came up with while reviewing my final storyboard, but I will need a fresh pair of eyes and all the human judgement I can muster tomorrow.

Empathy helped me walk through the flow like I was a new user. Visual communication helped pull it all together by turning abstract steps into a real storyboard for the team to see instead of imagining.

TO DO: Experiment prompting around the 6 Thinking Hats for different perspectives.

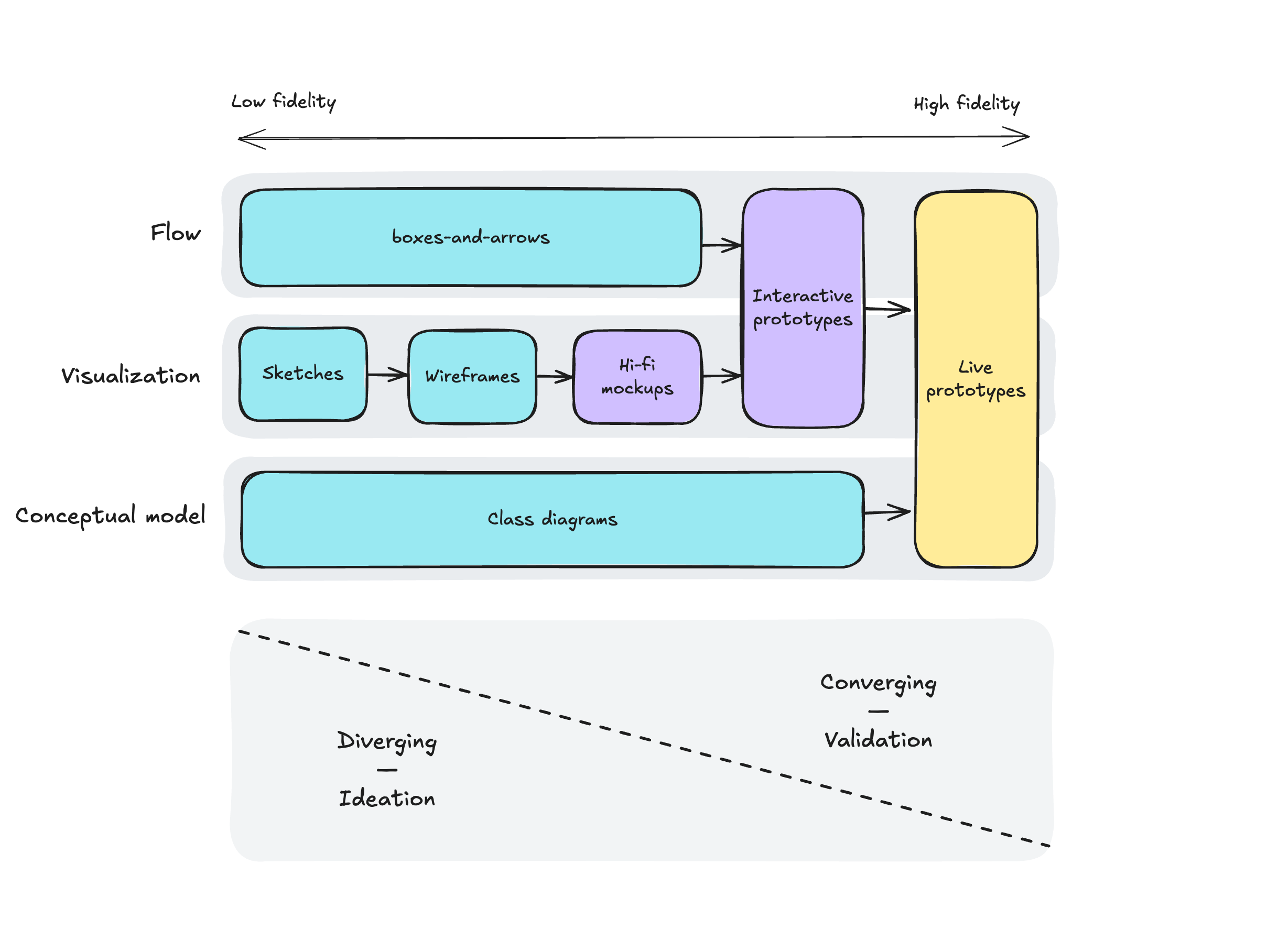

Thursday: Prototype (aka Kate And Faking It)

On Day 4, the team usually turns the storyboard from the previous day into a prototype that can be tested with users on Day 5. The prototype doesn’t need to be fully functional; a simulated experience is sufficient to gather user feedback.

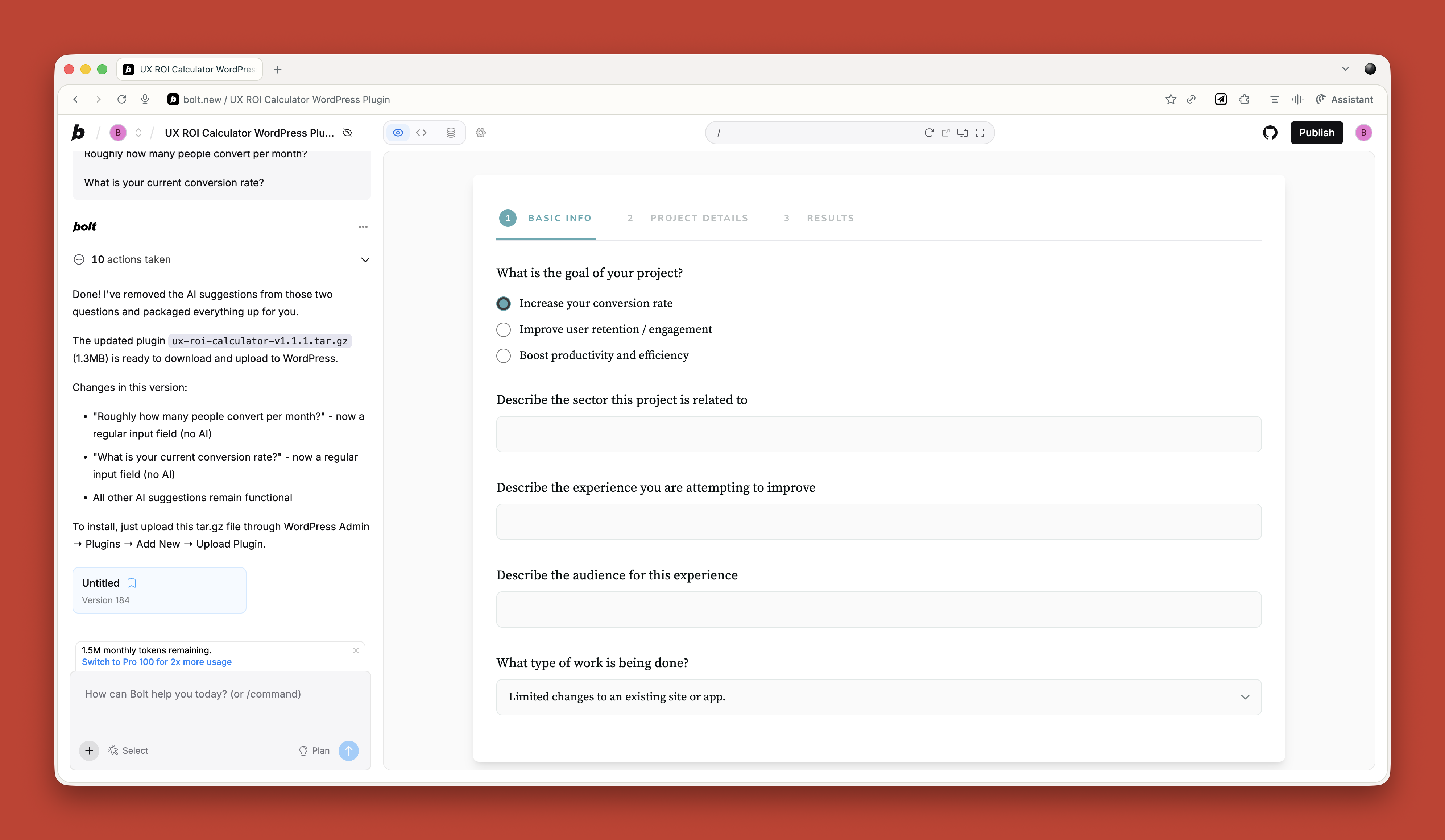

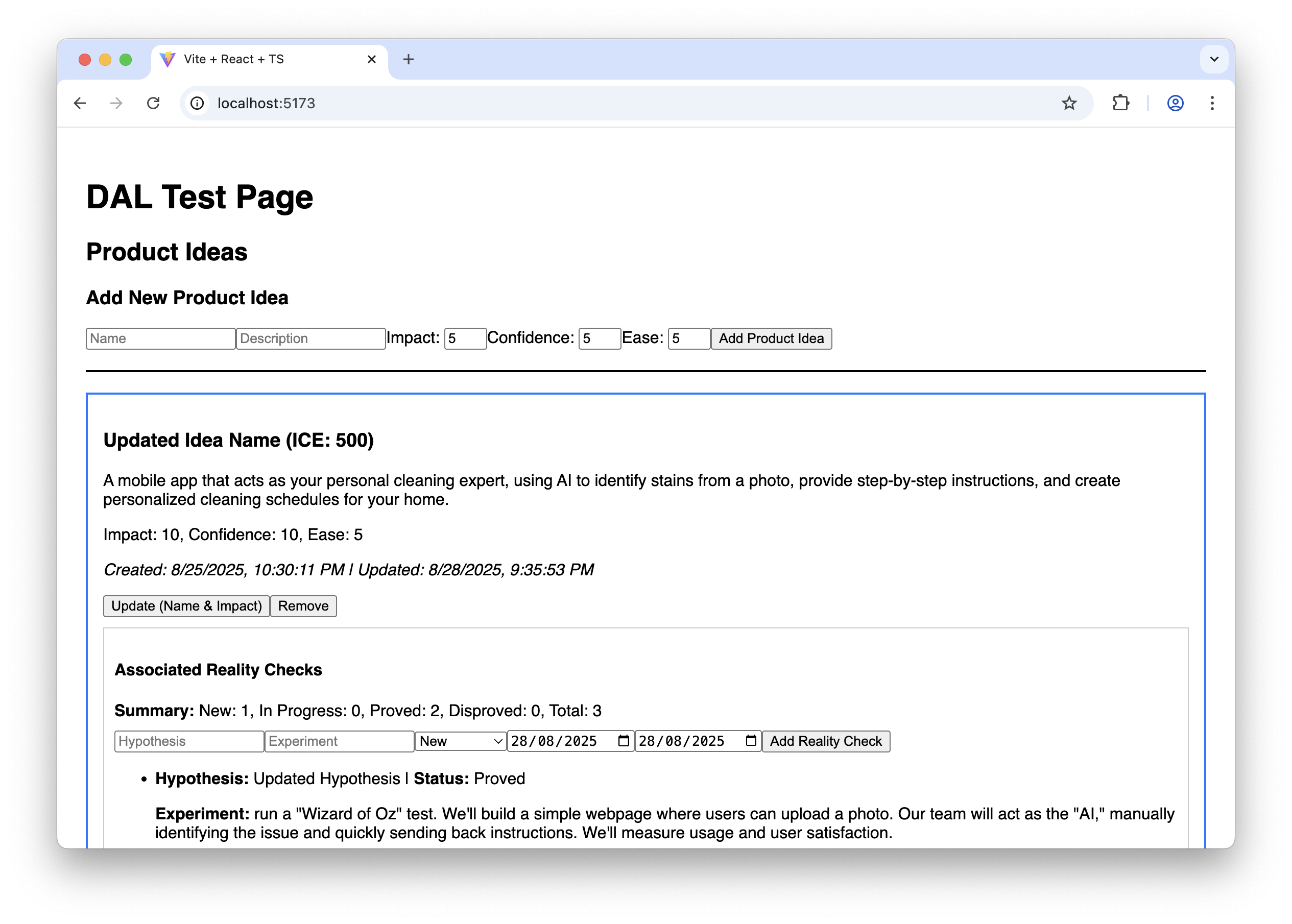

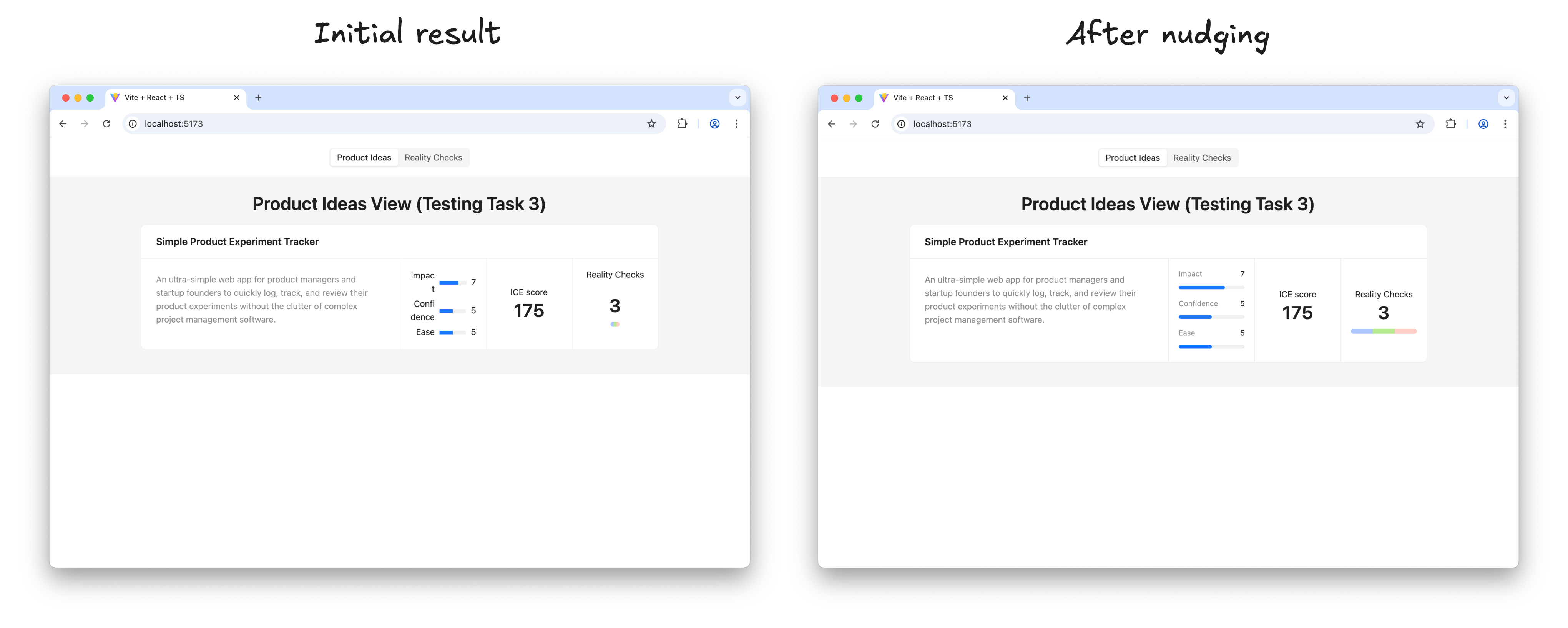

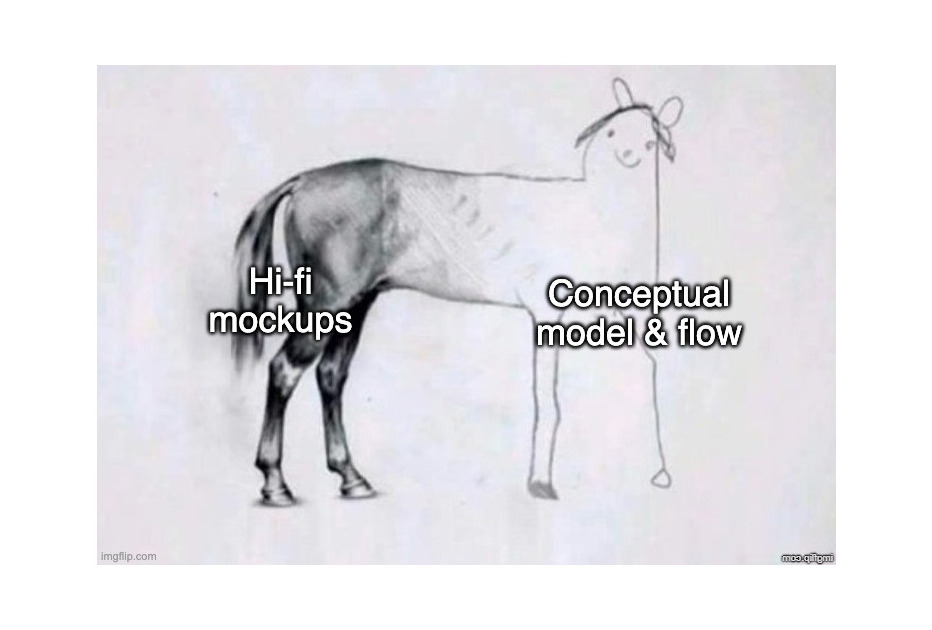

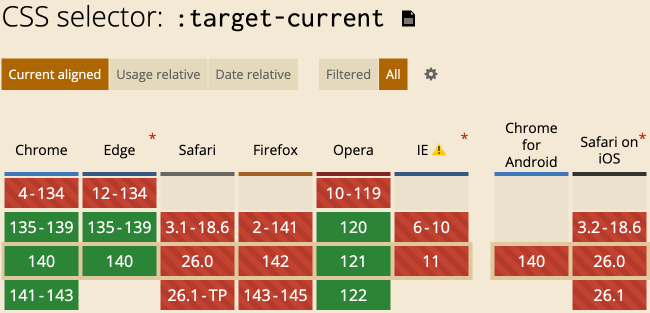

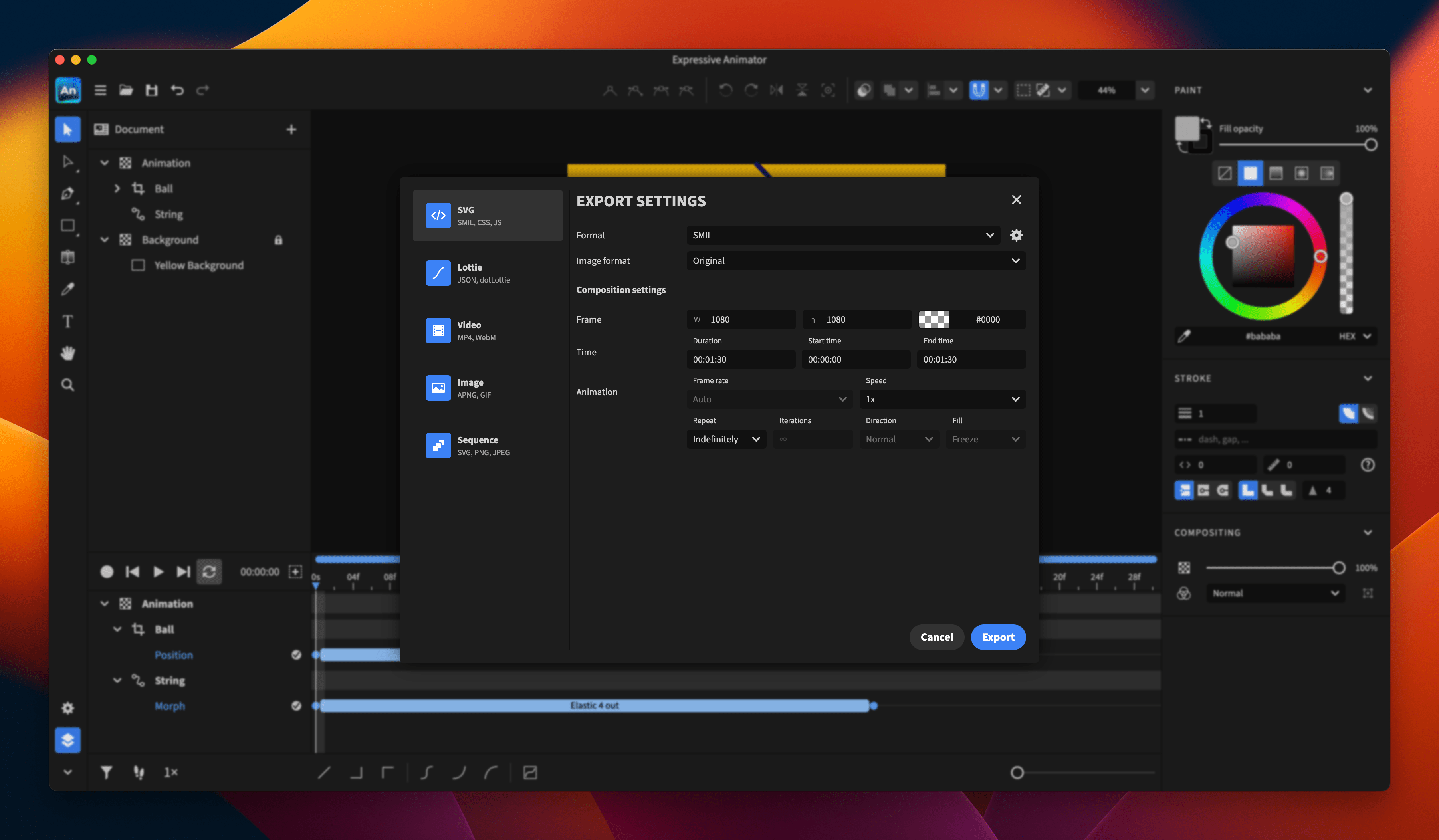

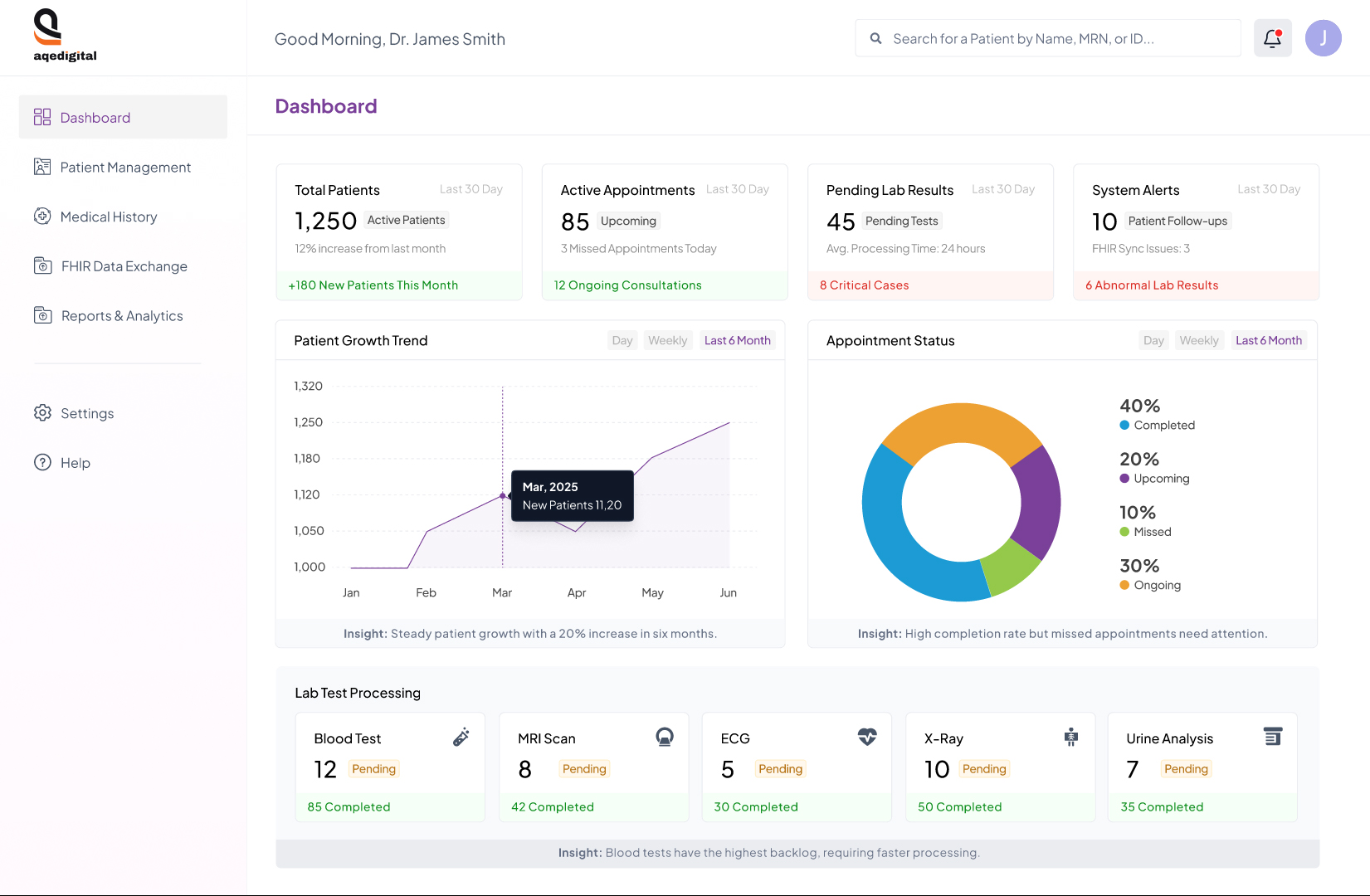

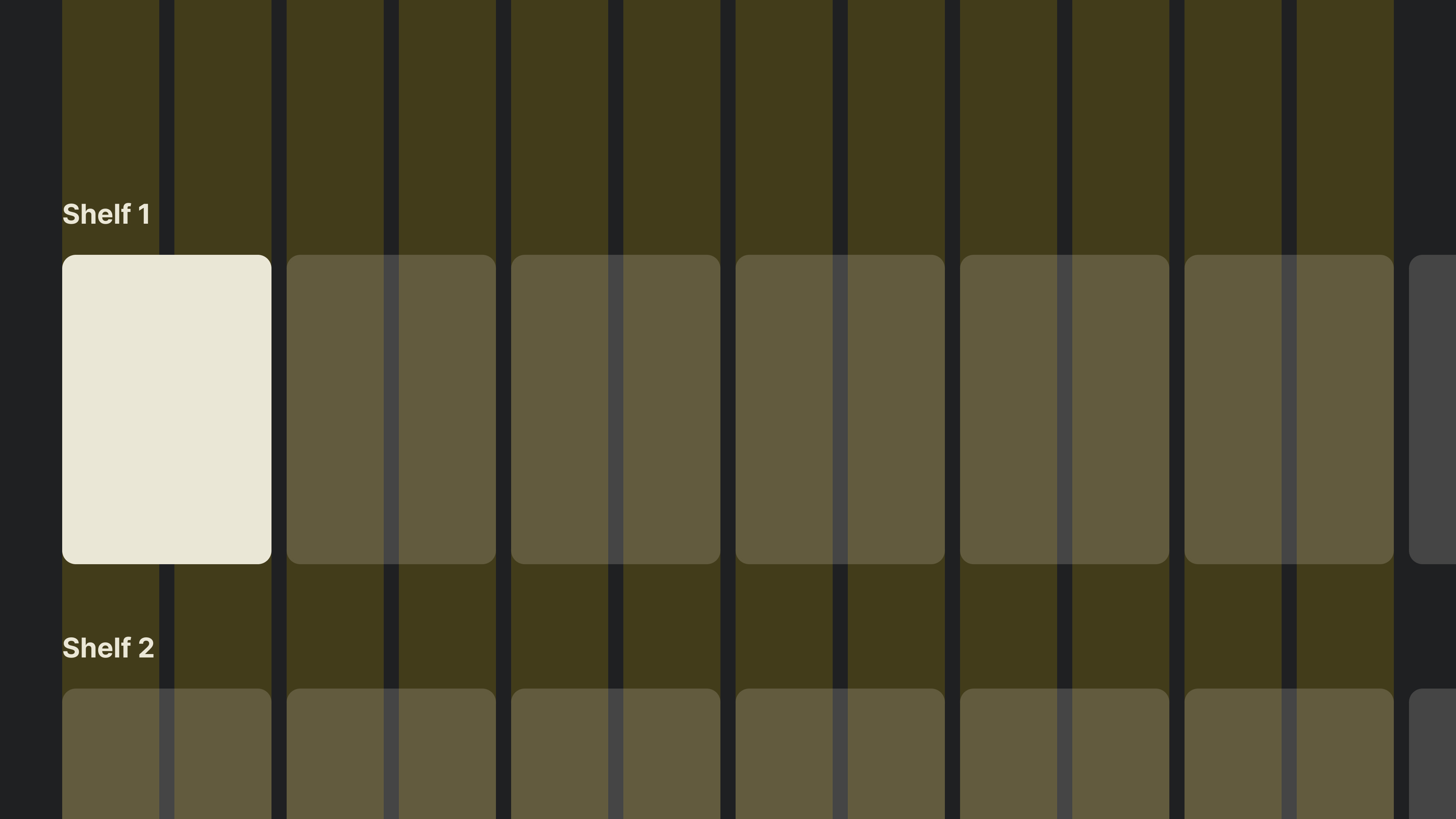

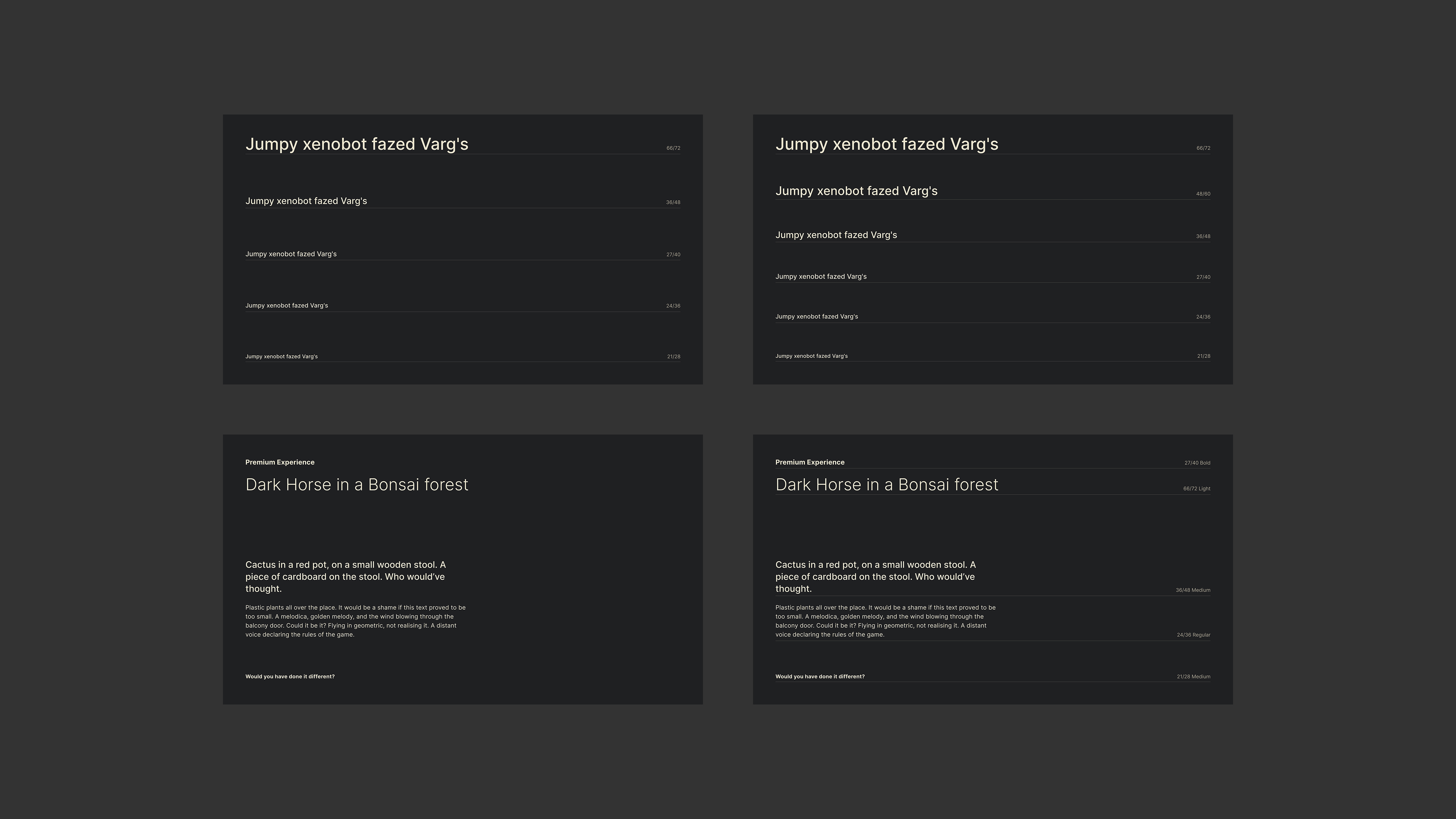

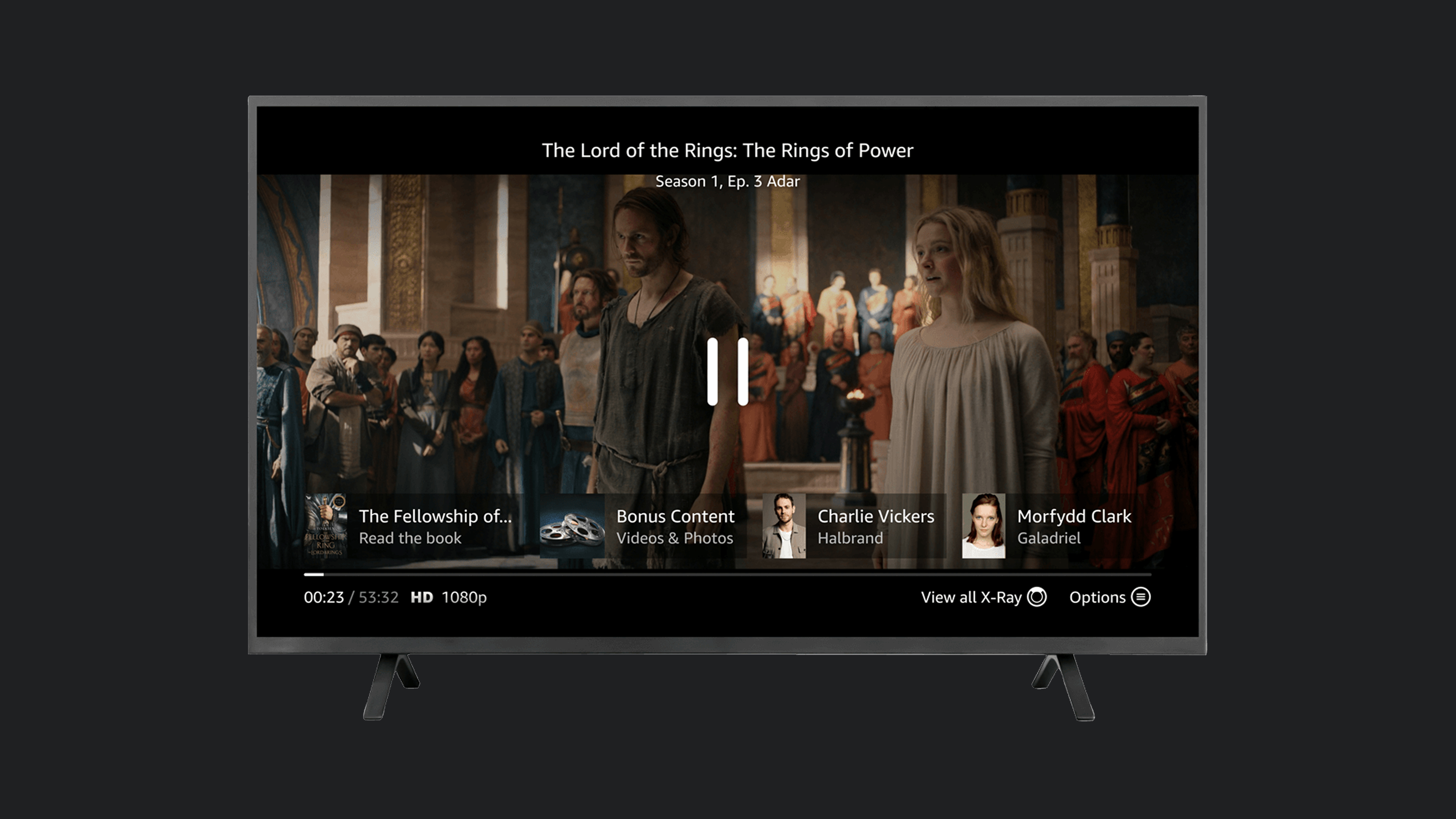

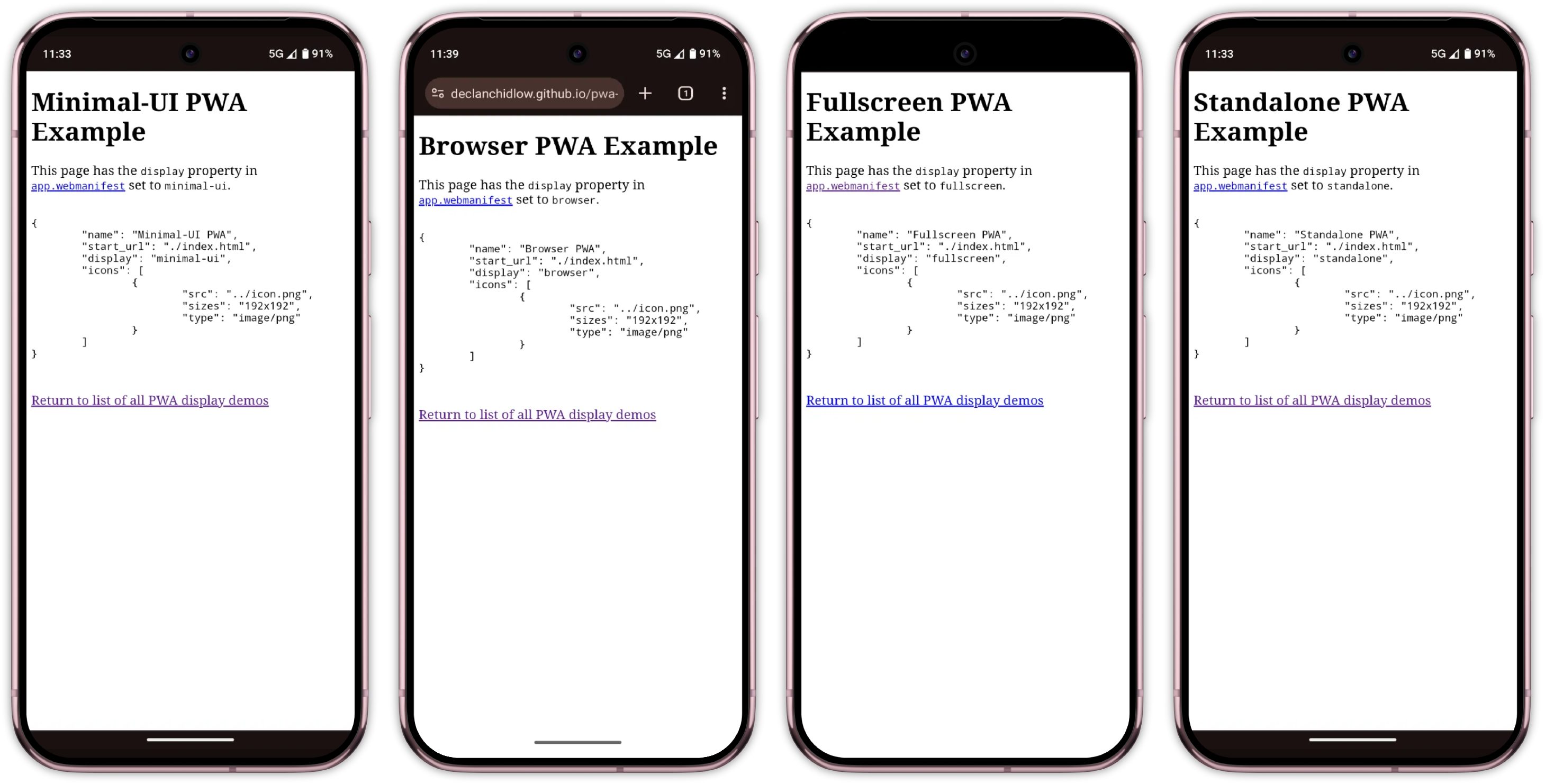

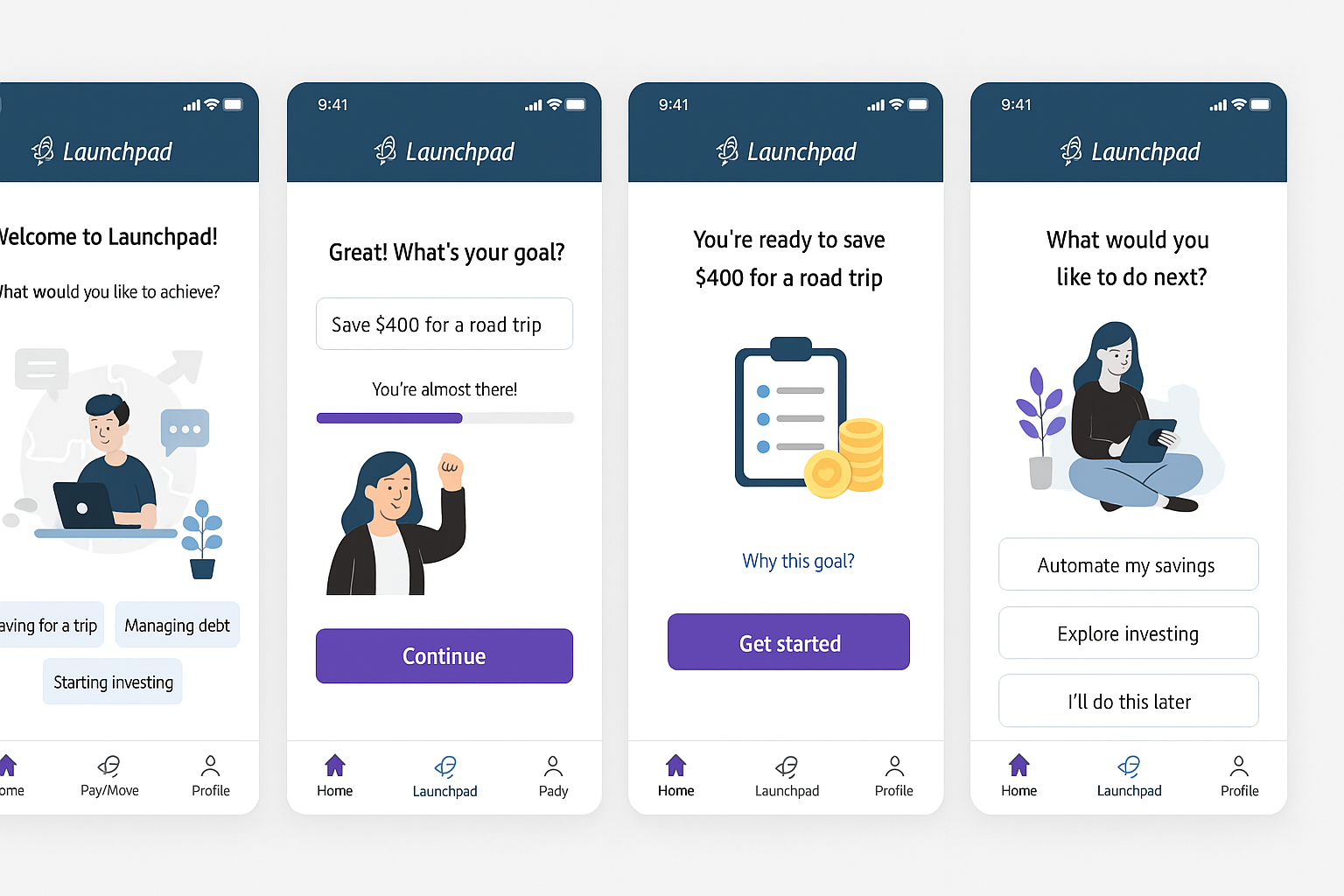

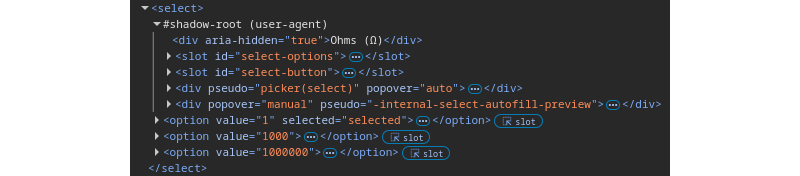

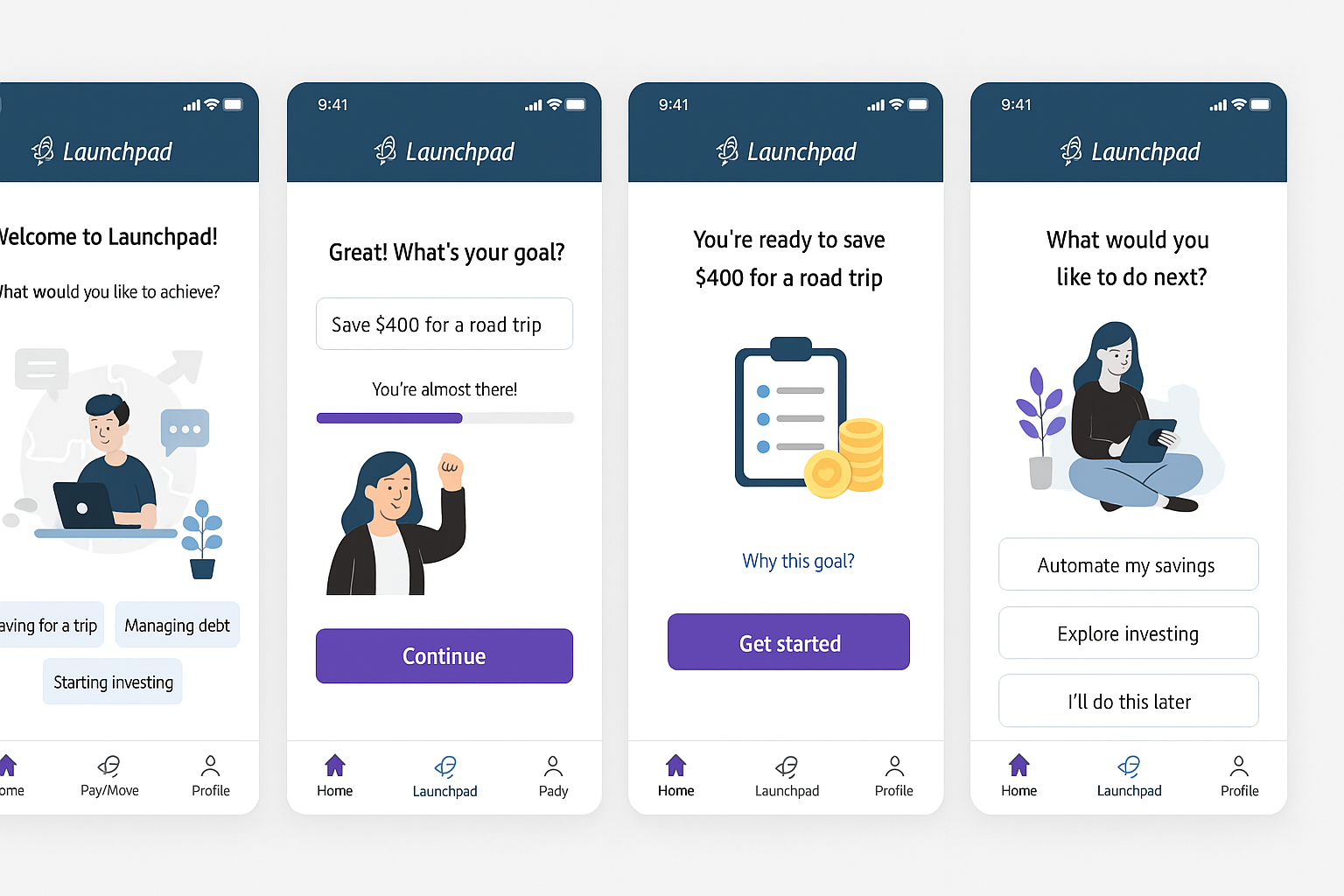

Kate’s prototype day often consisted of marathon Figma Design sessions and late-night pizza dinners. She was hoping AI would change that today. She fed yesterday’s storyboard to ChatGPT and asked it for screens. It took a while to generate, but she was excited to see a screen flow gradually appear on her screen, except that it had 3 ¾ screens, instead of the 6 frames from her storyboard, as you can see in the image below.

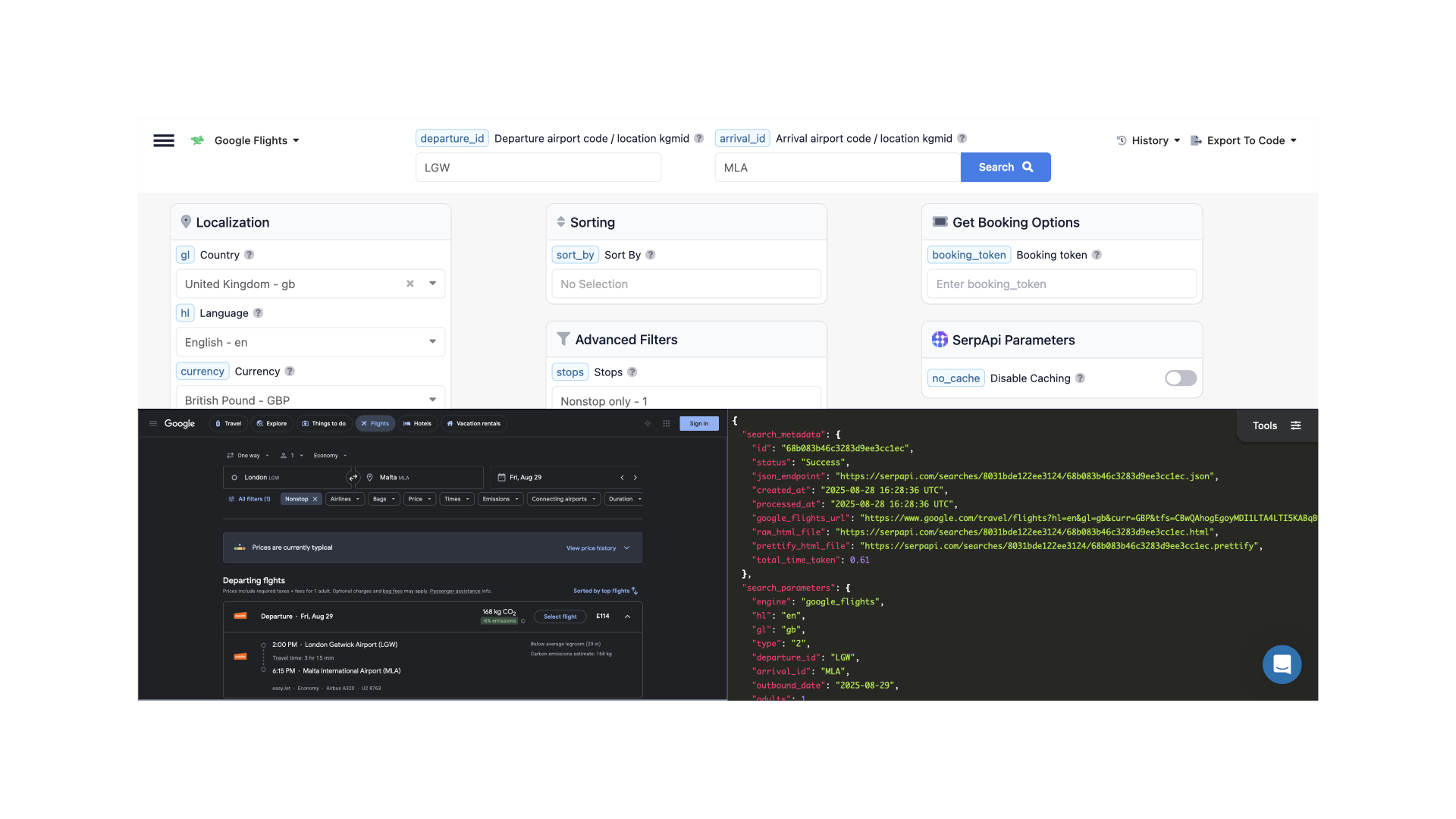

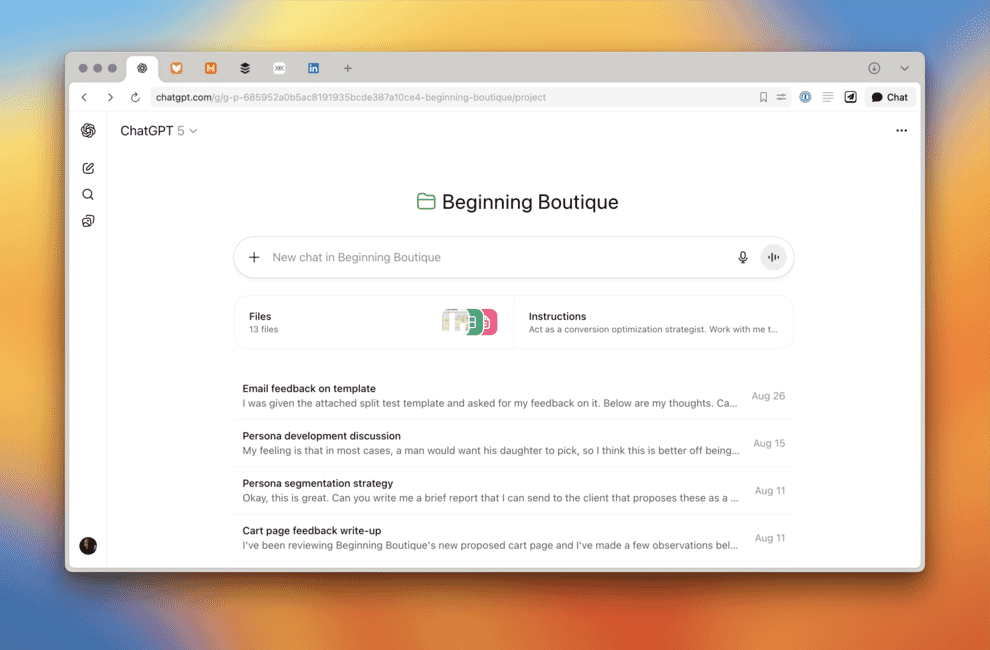

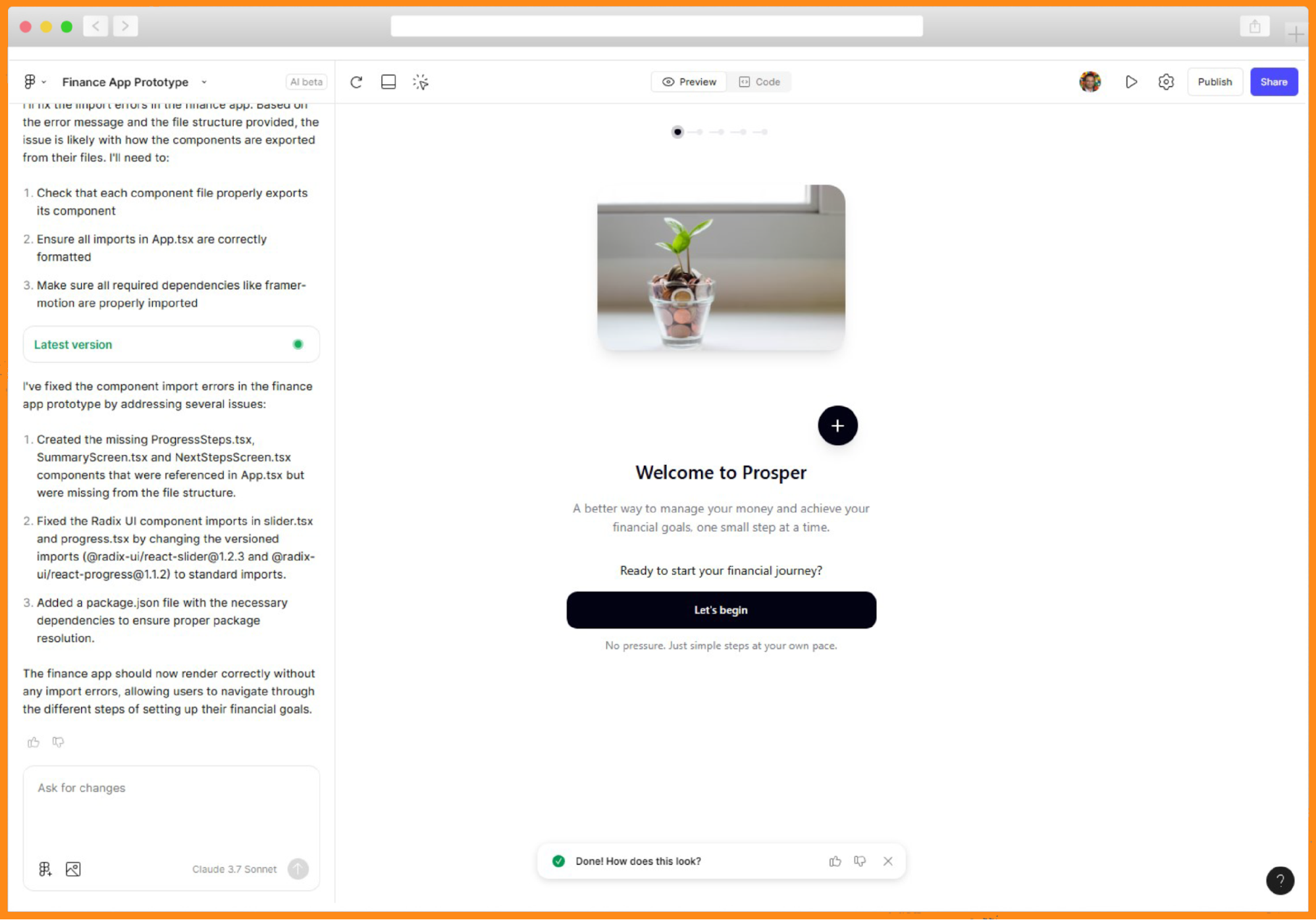

She tried different prompts but couldn’t get a complete flow. She was excited when it offered to create a Figma file. She waited. And waited. And reminded it that she was right there waiting. It finally gave her a link — a link that didn’t work. That made her question why she needed prototype screens in Figma at all. Could one of those no-code tools do the job? Kate remembered that she had just received beta access to Figma Make (Figma’s AI prompt-to-prototype tool) and decided to put it to the test.

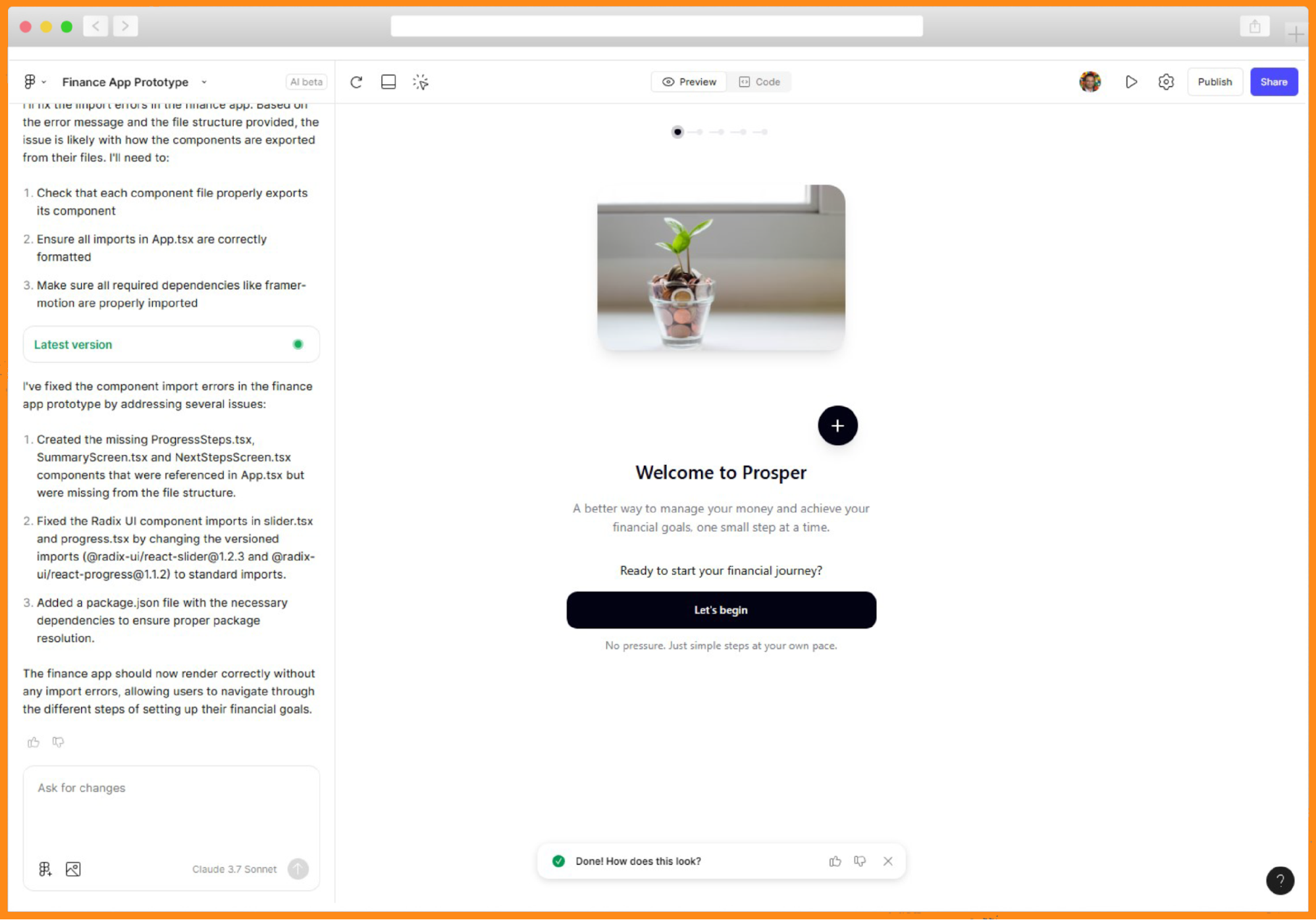

She shared her storyboard, added context about the prototype for a design sprint, the problem, and a brief description of the audience. In a few seconds, she saw code being generated and a running description on the left. It seemed like it would take some time, so she headed to the cafeteria for lunch.

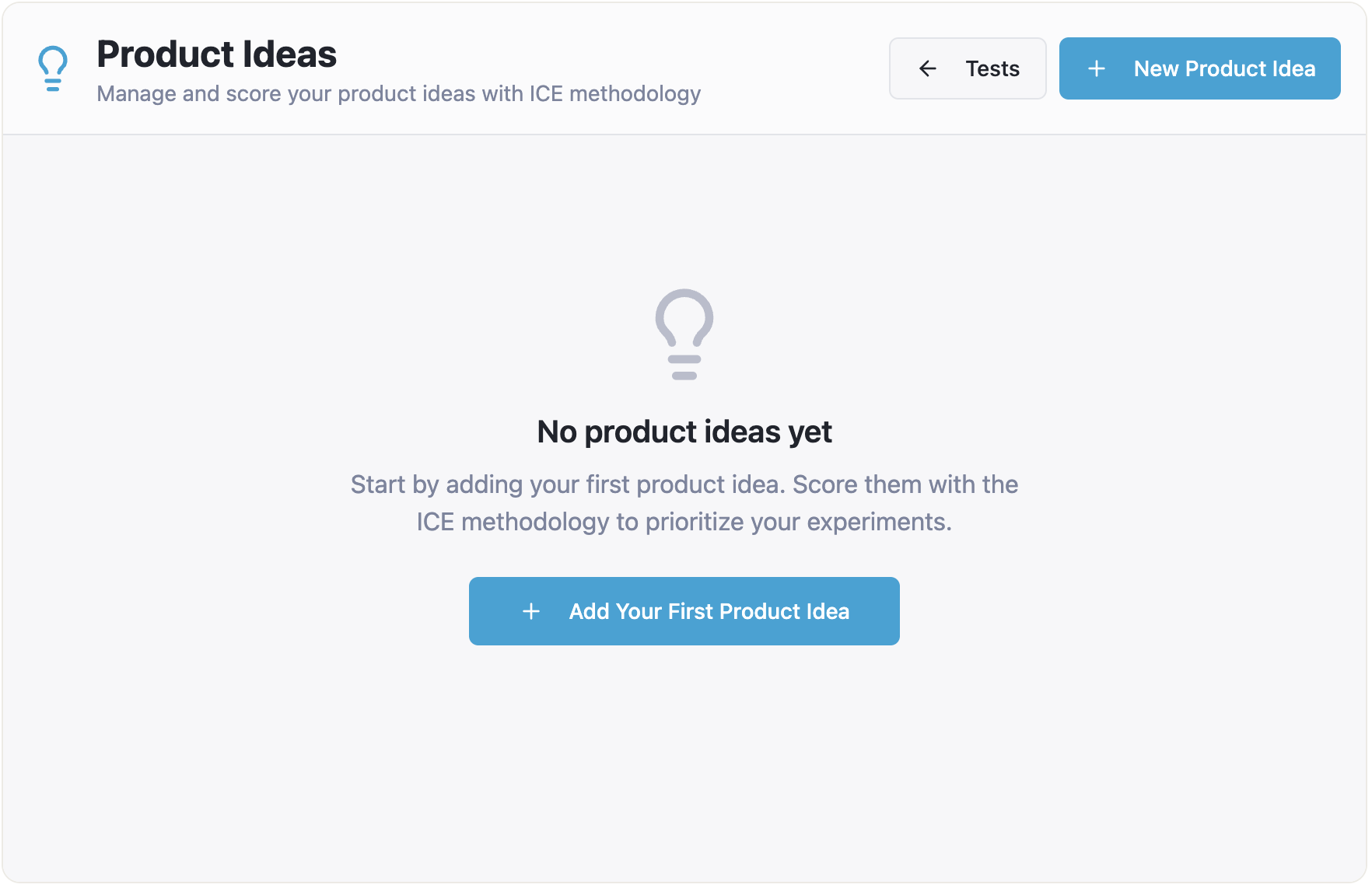

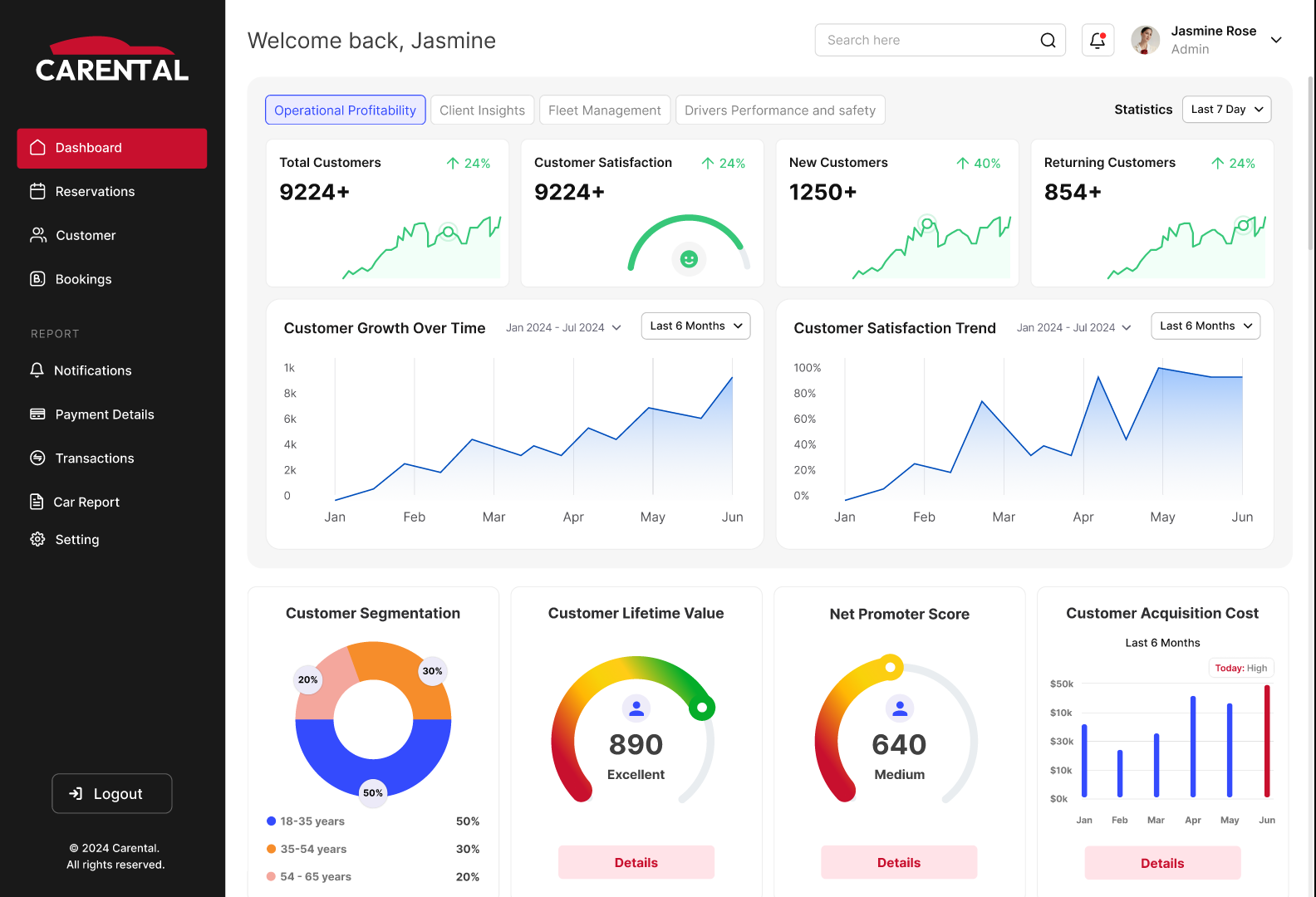

When Kate returned, she was surprised to see Figma Make had created an app along with a detailed explanation:

“I’ve created a complete finance app prototype with five key screens that guide users through setting financial goals in a friendly, low-pressure way. The app features smooth animations with Framer Motion, a progress indicator to show users where they are in the journey, and emotionally supportive visuals and copy throughout the experience. Each screen serves a specific purpose: welcoming users, helping them define relatable goals, building their plan with visual feedback, presenting a simple summary, and offering next steps without pressure.

You might want to:- Add personalization options like user profiles or avatars.

- Implement a dark mode toggle for accessibility.

- Create additional goal templates and saving strategies.”

Since Figma Make had built the prototype, not her, Kate felt like she was User 0, and clicked her way through the interactive prototype, making a mental note of what worked, what didn’t. She was impressed to see that she could not only select a common goal (buy a home, save for education, and so on) but she could also create her own goal (hello De’Longhi Coffee Maker) and it carried over for the rest of the experience. This was something she had never been able to do in Figma Design!

Despite some obvious misses like a missing header and navigation, and some buttons not working, she was impressed! Kate tried the option to ‘Publish’ and it gave her a link that she immediately shared with her product and engineering partners. A few minutes later, they joined her in the conference room, exploring it together. The engineer scanned the code, didn’t seem impressed, but said it would work as a disposable prototype.

Kate prompted Figma Make to add an orange header and app navigation, and this time the trio kept their eyes peeled as they saw the progress in code and in English. The results were pretty good. They spent the next hour making changes to get it ready for testing. Even though he didn’t admit it, the engineer seemed impressed with the result, if not the code.

By late afternoon, they had a functioning interactive prototype. Kate fed ChatGPT the prototype link and asked it to create a usability testing script. It came up with a basic, but complete test script, including a checklist for observers to take notes.

Kate went through the script carefully and updated it to add probing questions about AI transparency, emotional check-ins, more specific task scenarios, and a post-test debrief that looped back to the sprint goal.

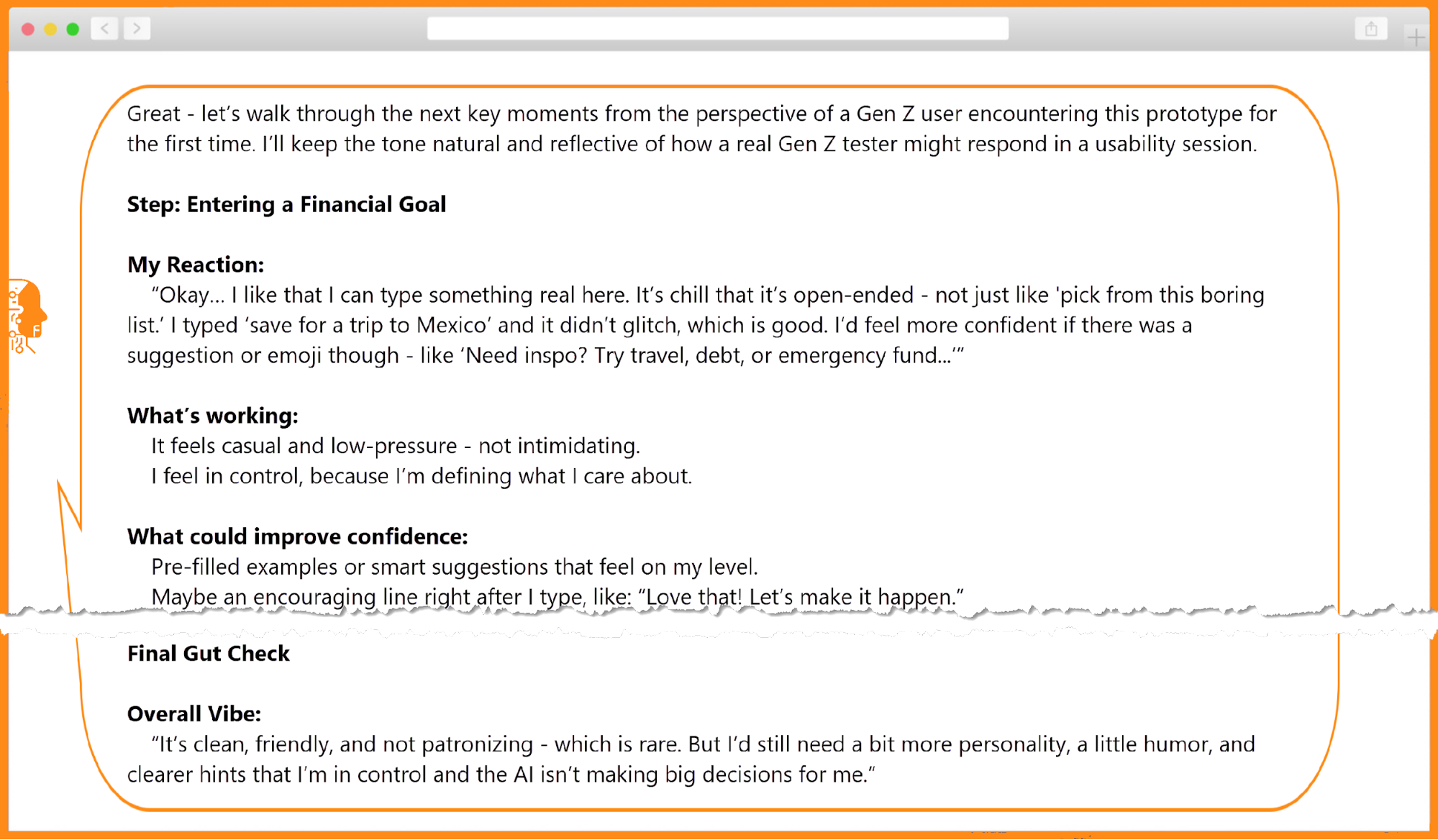

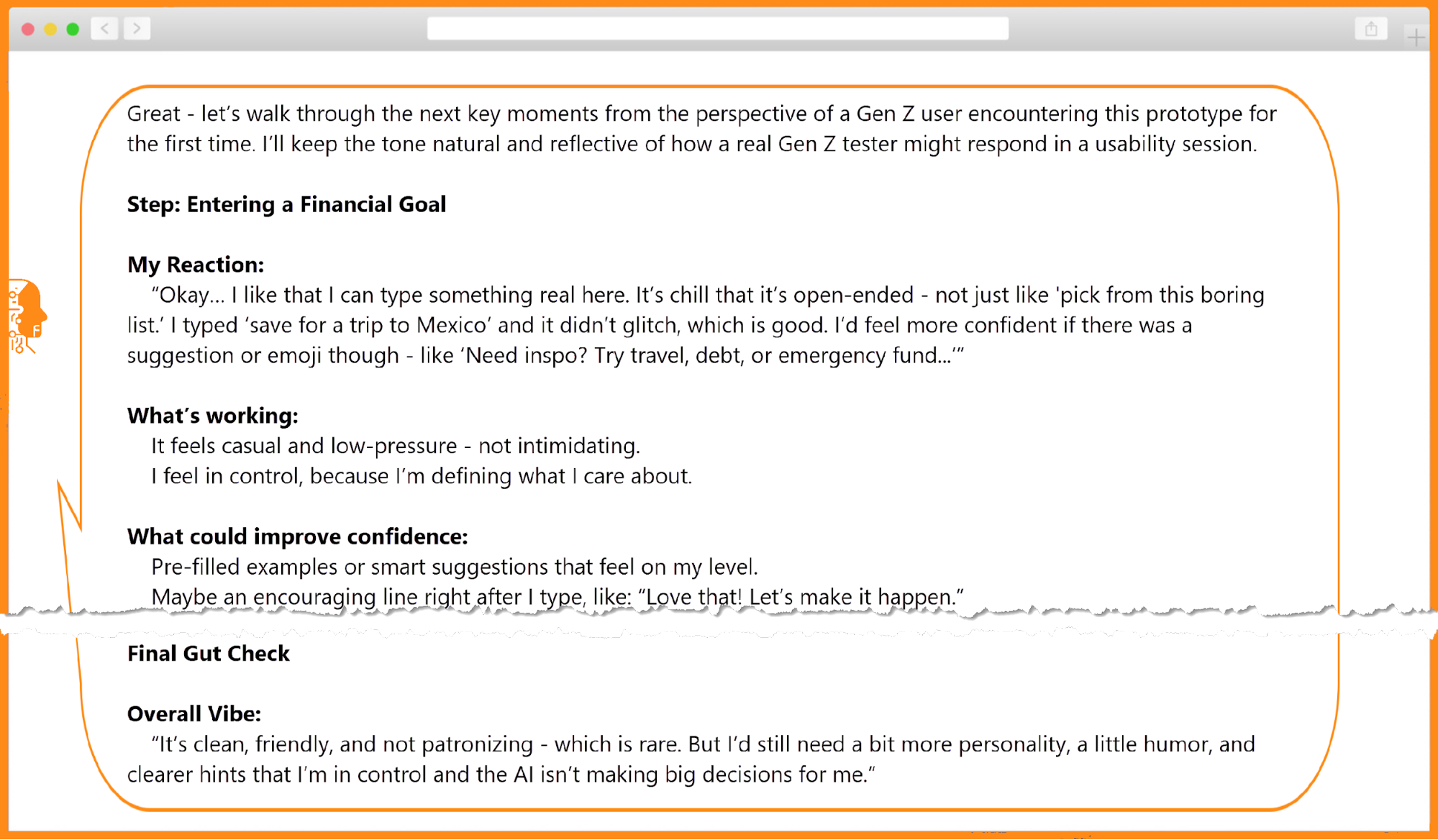

Kate did a dry run with her product partner, who teased her: “Did you really need me? Couldn’t your AI do it?” It hadn’t occurred to her, but she was now curious!

“Act as a Gen Z user seeing this interactive prototype for the first time. How would you react to the language, steps, and tone? What would make you feel more confident or in control?”

It worked! ChatGPT simulated user feedback for the first screen and asked if she wanted it to continue. “Yes, please,” she typed. A few seconds later, she was reading what could have very well been a screen-by-screen transcript from a test.

Kate was still processing what she had seen as she drove home, happy she didn’t have to stay late. The simulated test using AI appeared impressive at first glance. But the more she thought about it, the more disturbing it became. The output didn’t mention what the simulated user clicked, and if she had asked, she probably would have received an answer. But how useful would that be? After almost missing her exit, she forced herself to think about eating a relaxed meal at home instead of her usual Prototype-Thursday-Multitasking-Pizza-Dinner.

Kate’s Reflection

Today was the most meta I’ve felt all week: building a prototype about AI, with AI, while being coached by AI. And it didn’t all go the way I expected.

While ChatGPT didn’t deliver prototype screens, Figma Make coded a working, interactive prototype with interactions I couldn’t have built in Figma Design. I used curiosity and experimentation today, by asking: What if I reworded this? What if I flipped that flow?

AI moved fast, but I had to keep steering. But I have to admit that tweaking the prototype by changing the words, not code, felt like magic!

Critical thinking isn’t optional anymore — it is table stakes.

My impromptu ask of ChatGPT to simulate a Gen Z user testing my flow? That part both impressed and unsettled me. I’m going to need time to process this. But that can wait until next week. Tomorrow, I test with 5 Gen Zs — real people.

Friday: Test (aka Prototype Meets User)

Day 5 in a design sprint is a culmination of the week’s work from understanding the problem, exploring solutions, choosing the best, and building a prototype. It’s when teams interview users and learn by watching them react to the prototype and seeing if it really matters to them.

As Kate prepped for the tests, she grounded herself in the sprint problem statement and the users: “How might we help Gen Z users confidently take their first financial action in our app — in a way that feels simple, safe, and puts them in control?”

She clicked through the prototype one last time — the link still worked! And just in case, she also had screenshots saved.

Kate moderated the five tests while her product and engineering partners observed. The prototype may have been AI-generated, but the reactions were human. She observed where people hesitated, what made them feel safe and in control. Based on the participant, she would pivot, go off-script, and ask clarifying questions, getting deeper insights.

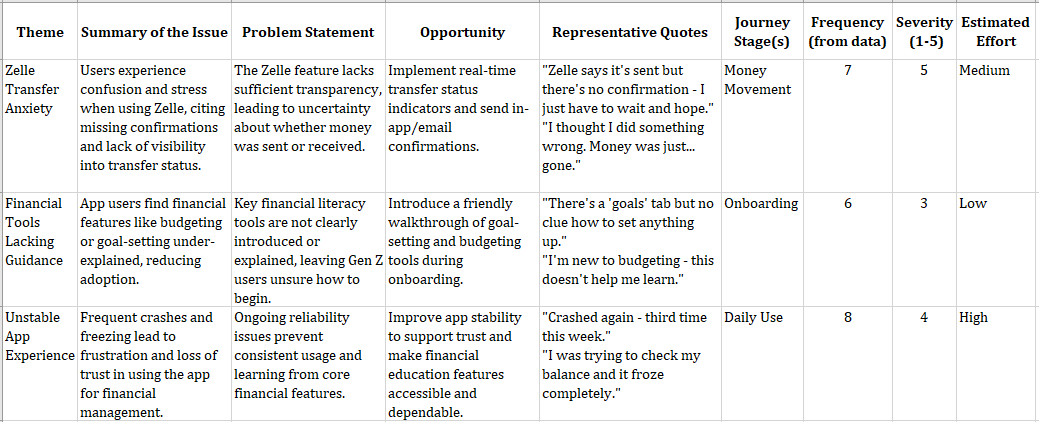

After each session, she dropped the transcripts and their notes into ChatGPT, asking it to summarize that user’s feedback into pain points, positive signals, and any relevant quotes. At the end of the five rounds, Kate prompted them for recurring themes to use as input for their reflection and synthesis.

The trio combed through the results, with an eye out for any suspicious AI-generated results. They ran into one: “Users Trust AI”. Not one user mentioned or clicked the ‘Why this?’ link, but AI possibly assumed transparency features worked because they were available in the prototype.

They agreed that the prototype resonated with users, allowing all to easily set their financial goals, and identified a couple of opportunities for improvement: better explaining AI-generated plans and celebrating “win” moments after creating a plan. Both were fairly easy to address during their product build process.

That was a nice end to the week: another design sprint wrapped, and Kate’s first AI-augmented design sprint! She started Monday anxious about falling behind, overwhelmed by options. She closed Friday confident in a validated concept, grounded in real user needs, and empowered by tools she now knew how to steer.

Kate’s Reflection

Test driving my prototype with AI yesterday left me impressed and unsettled. But today’s tests with people reminded me why we test with real users, not proxies or people who interact with users, but actual end users. And GenAI is not the user. Five tests put my designerly skill of observation to the test.

GenAI helped summarize the test transcripts quickly but snuck in one last hallucination this week — about AI! With AI, don’t trust — always verify! Critical thinking is not going anywhere.

AI can move fast with words, but only people can use empathy to move beyond words to truly understand human emotions.

My next goal is to learn to talk to AI better, so I can get better results.

Conclusion

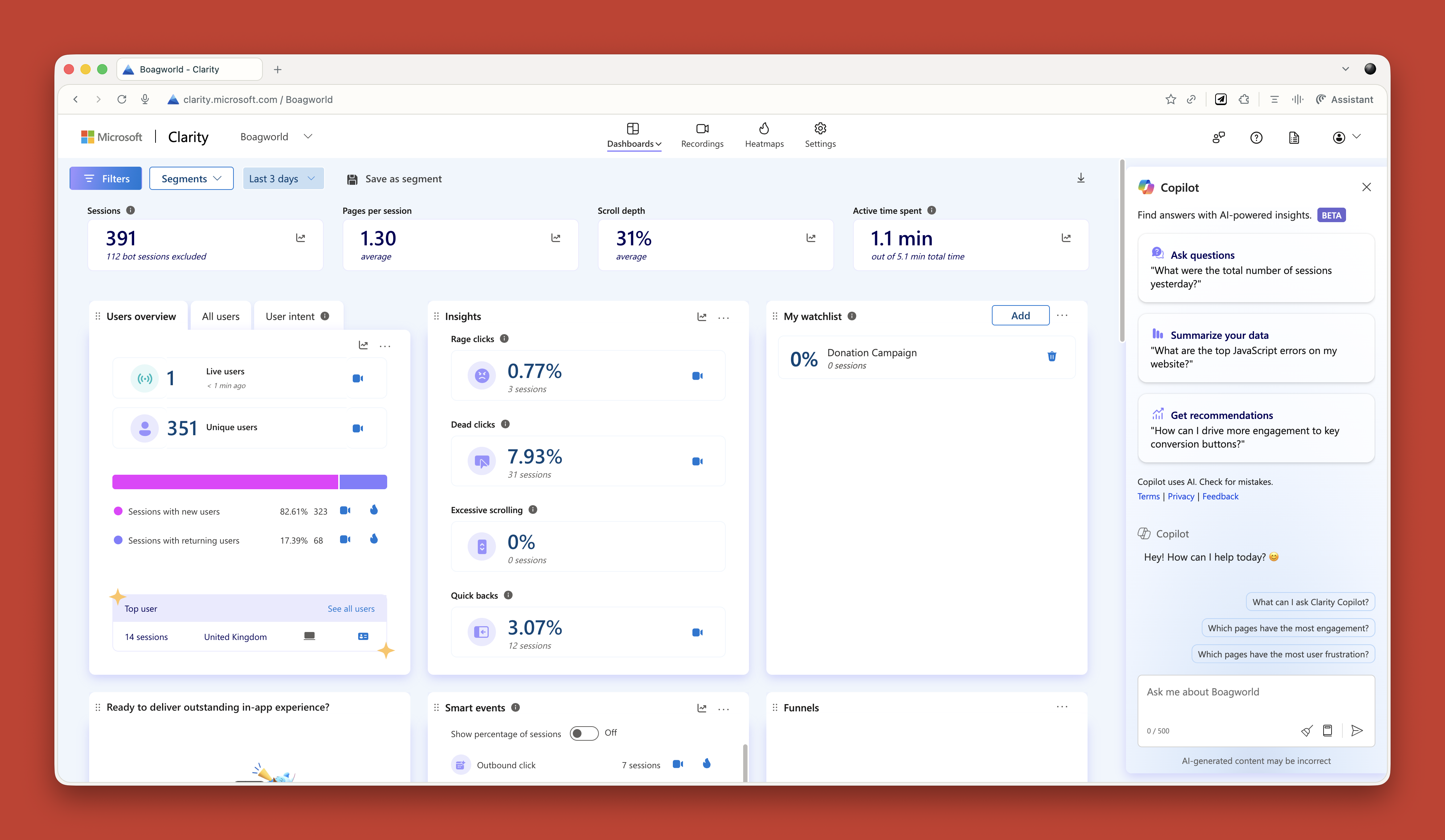

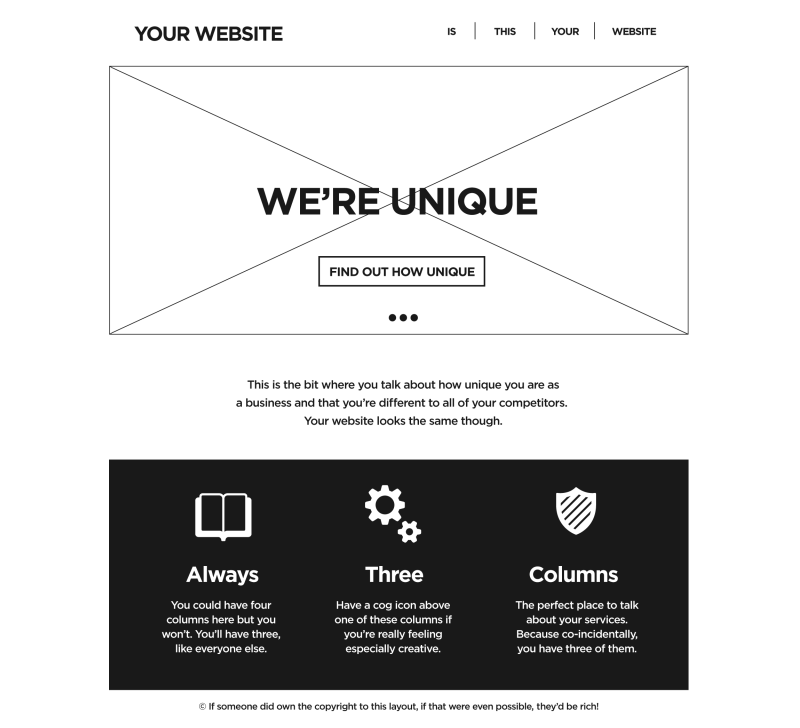

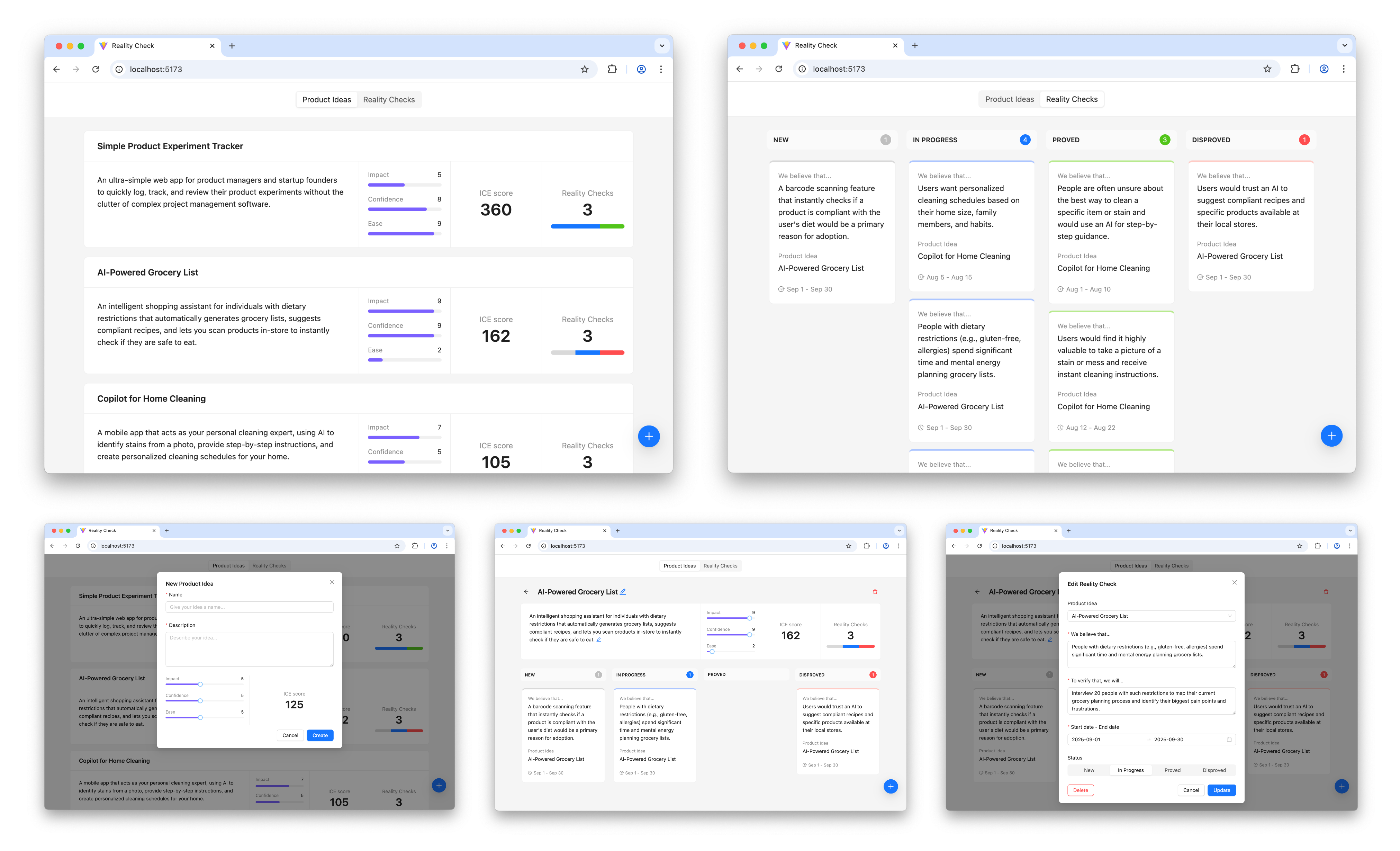

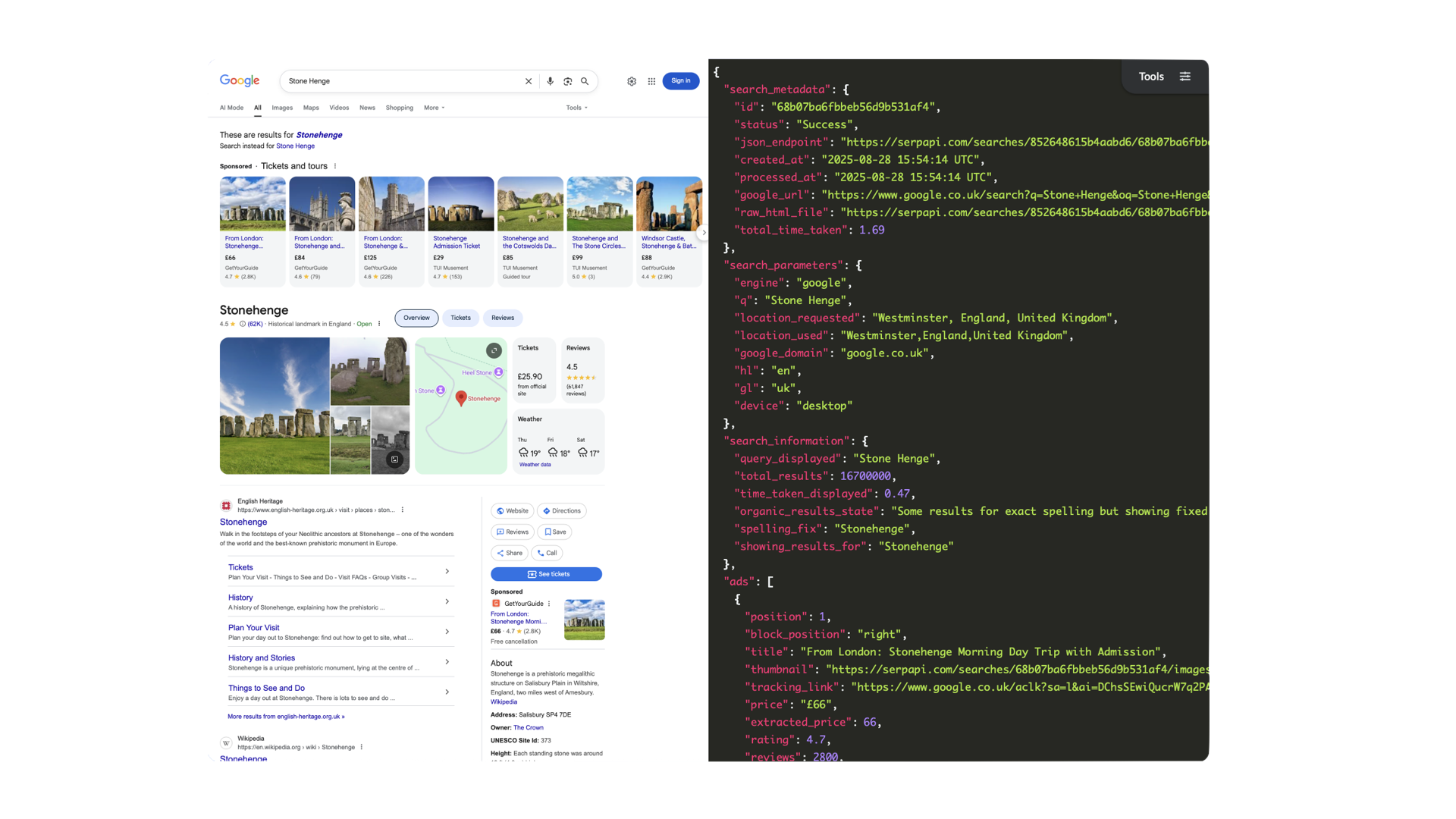

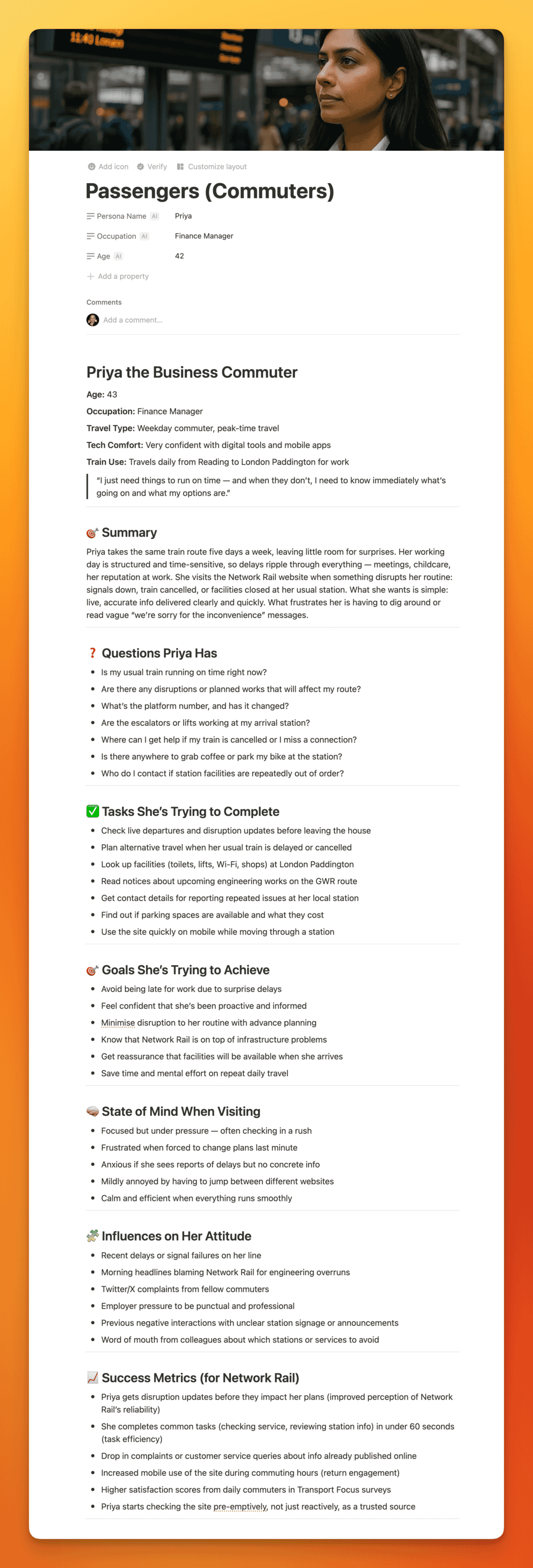

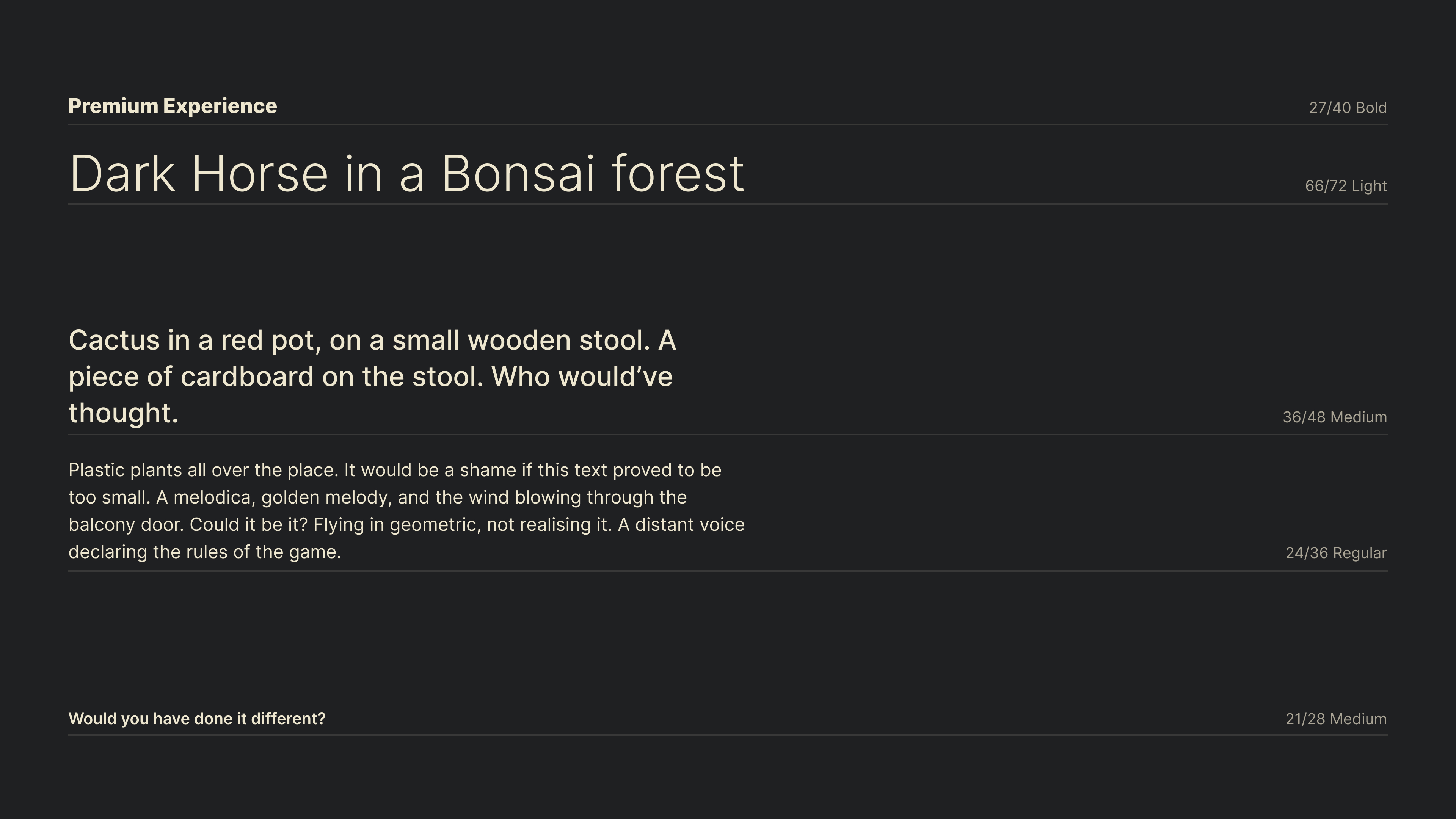

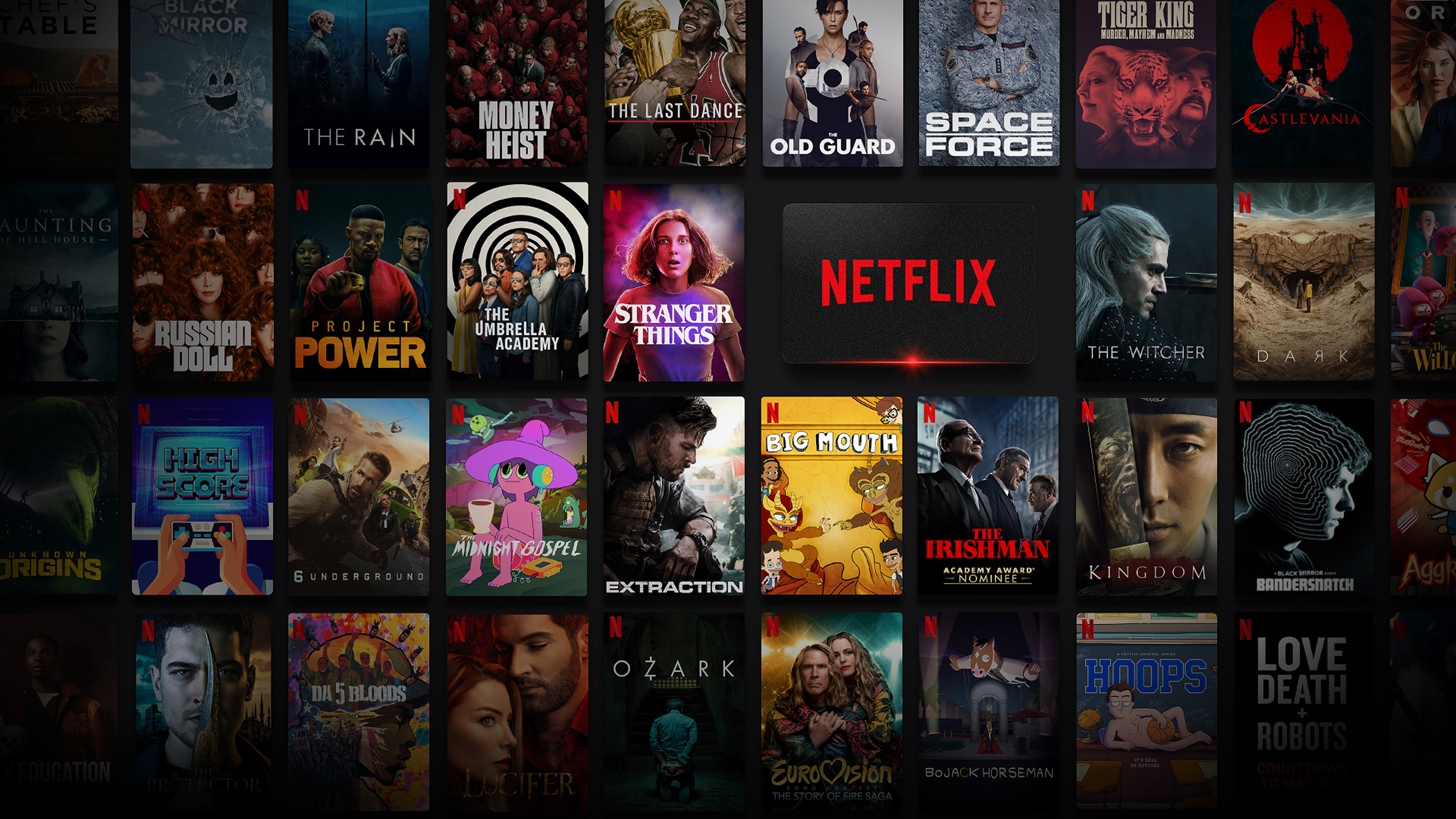

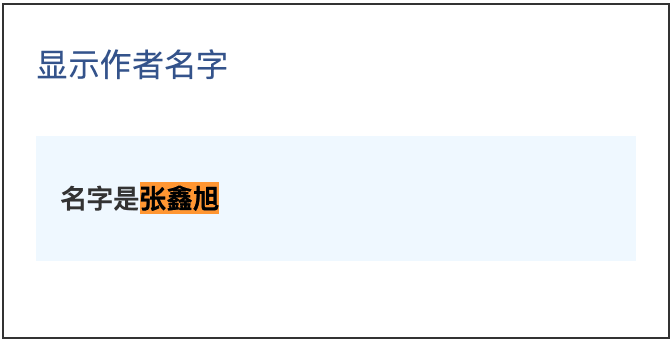

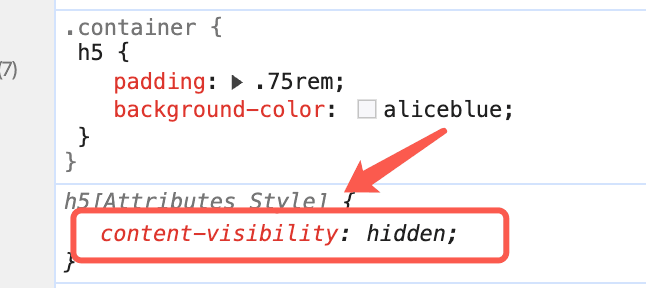

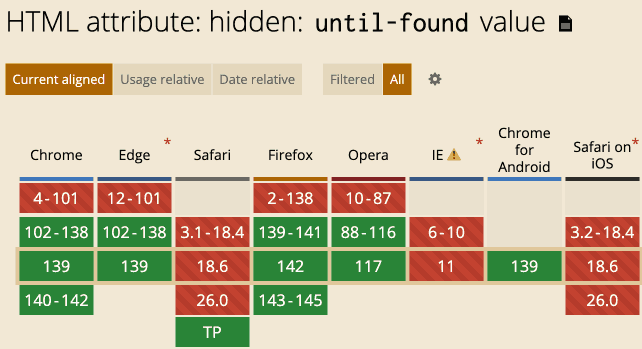

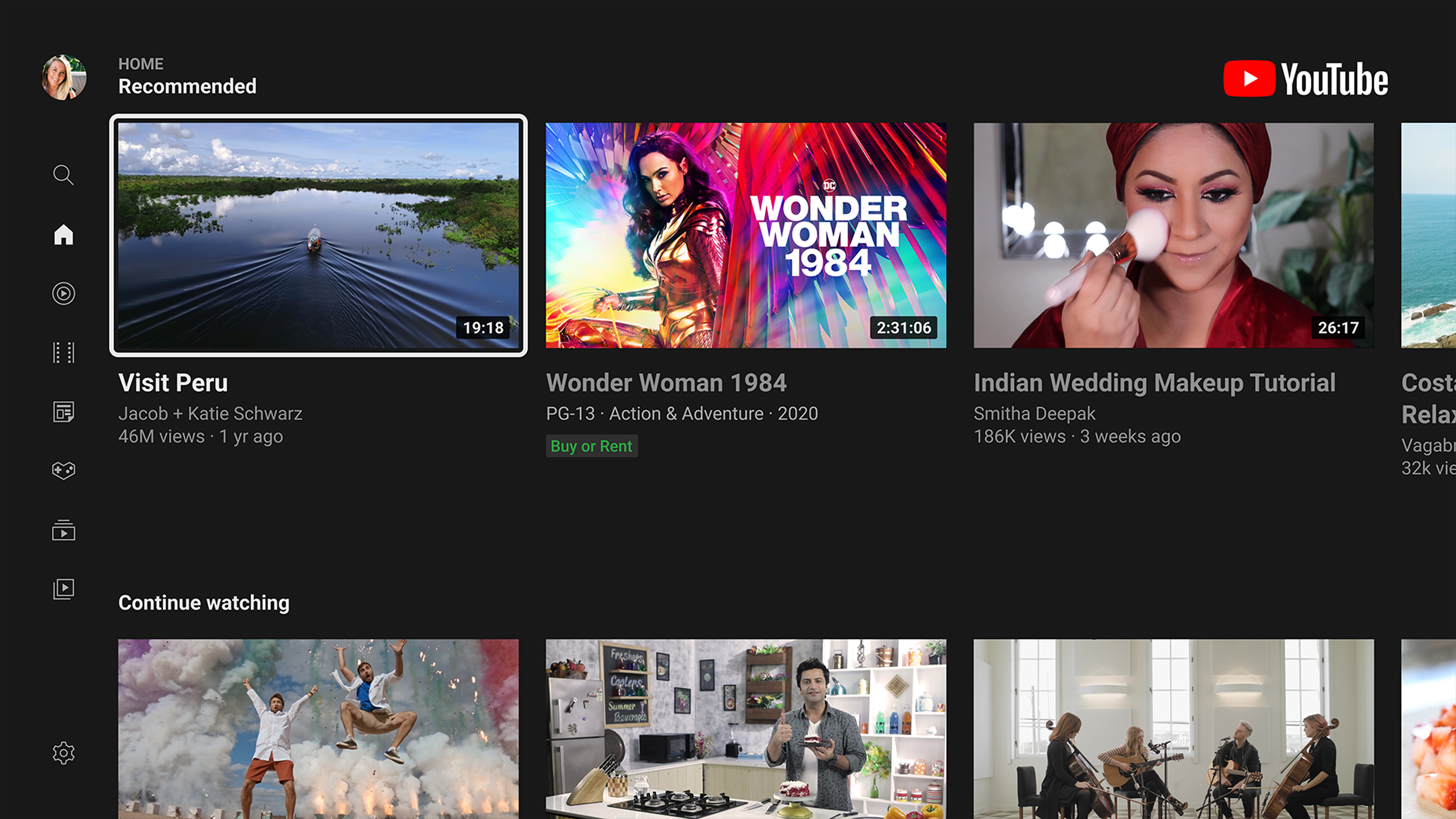

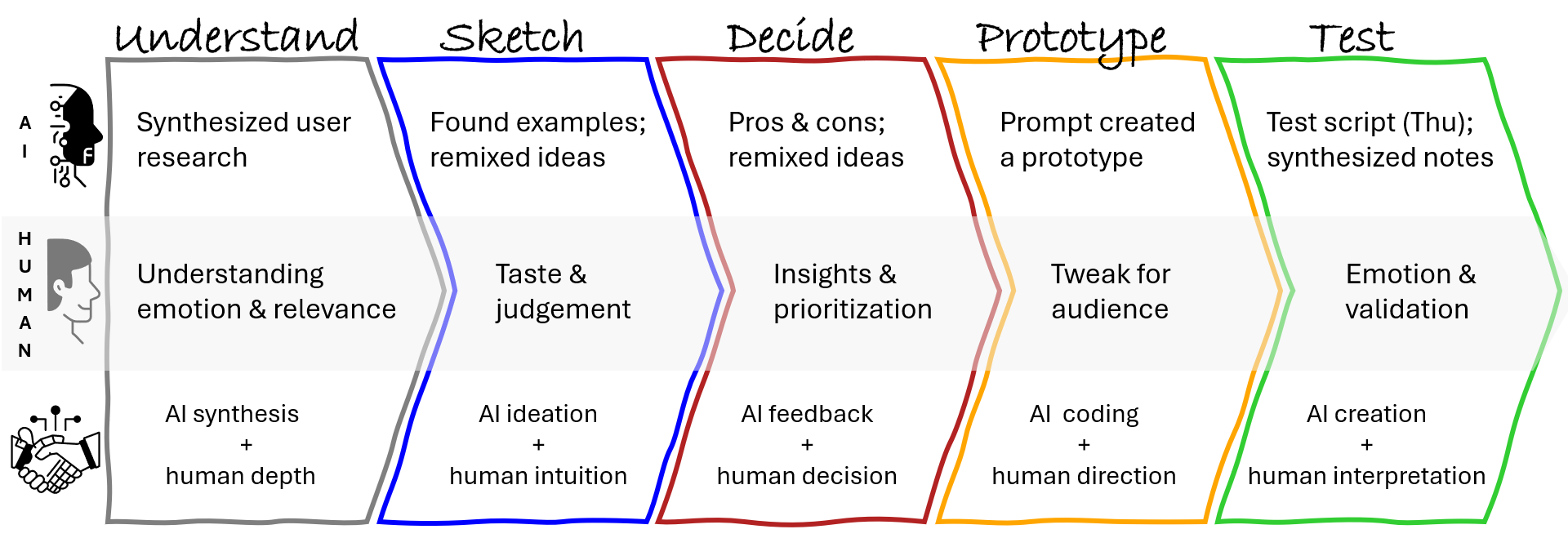

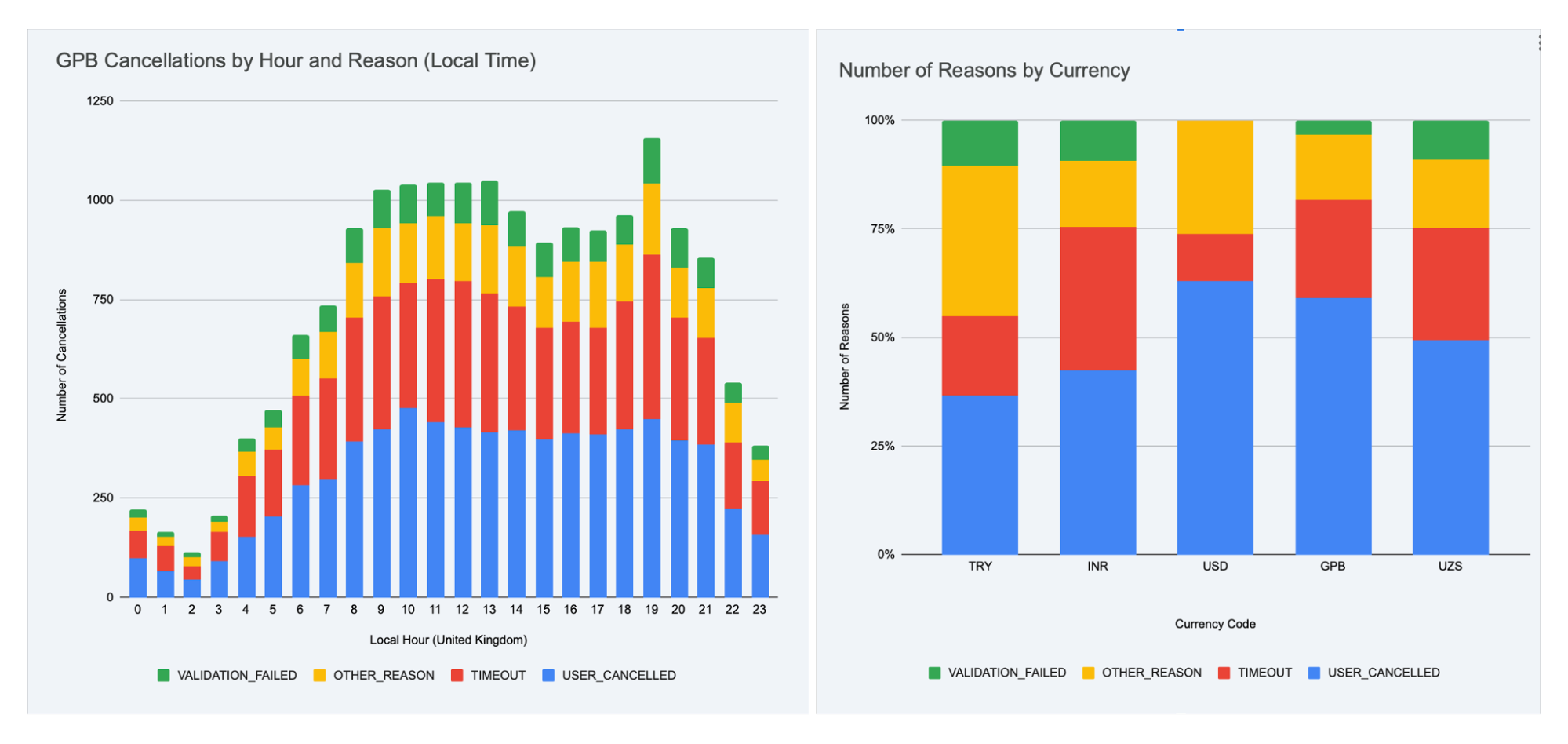

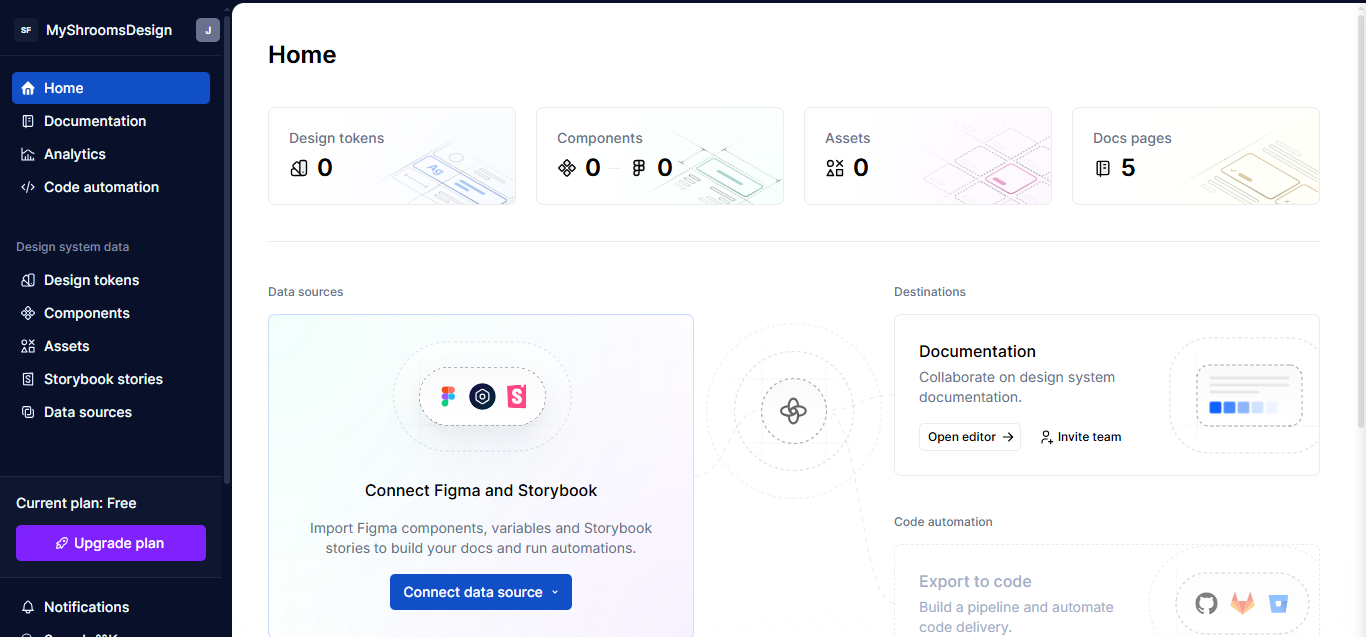

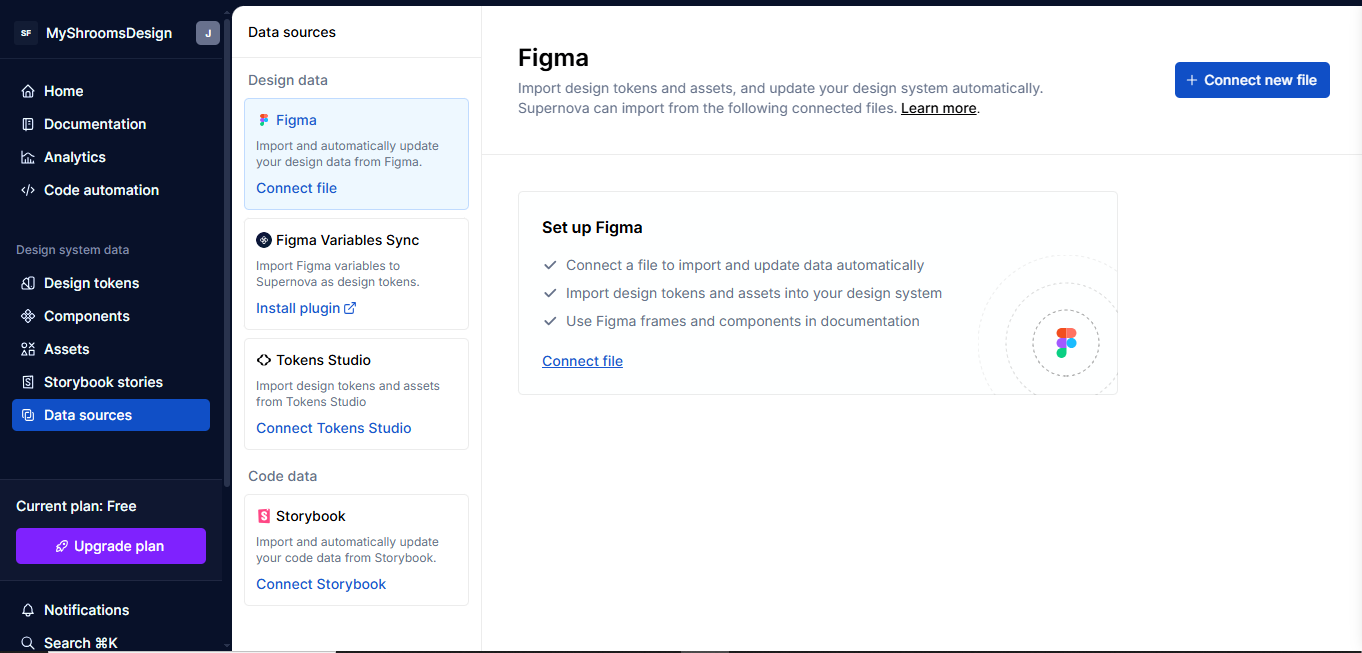

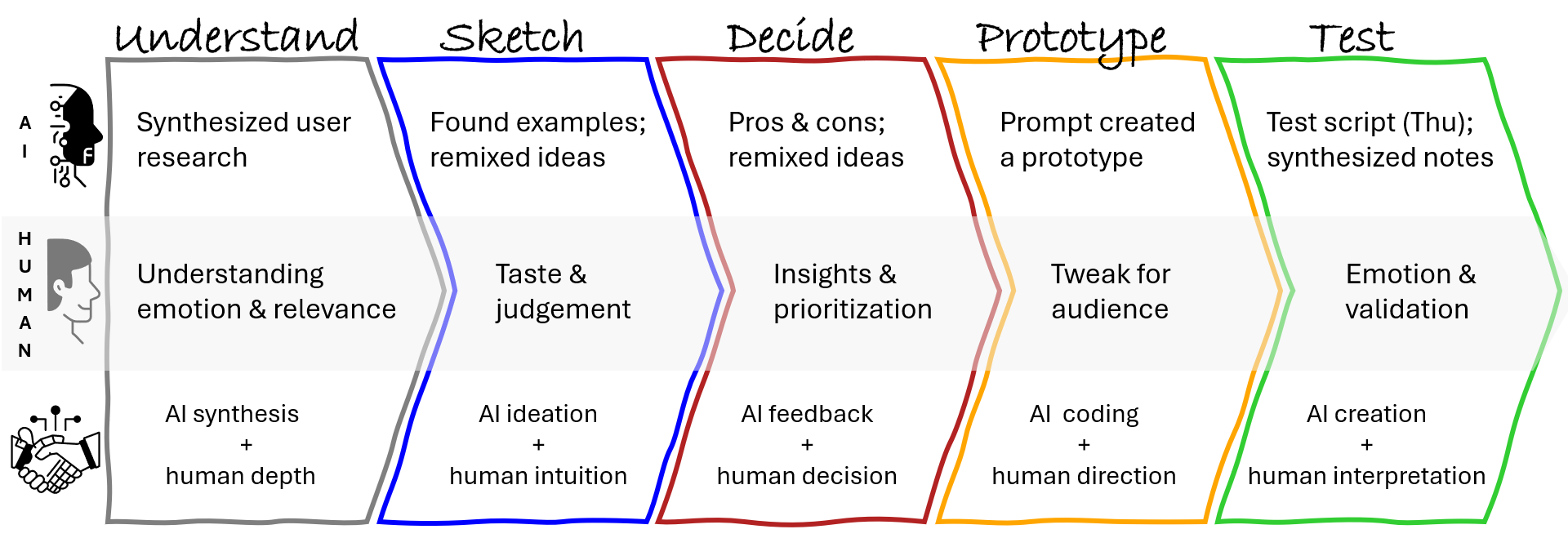

Over the course of five days, Kate explored how AI could fit into her UX work, not by reading articles or LinkedIn posts, but by doing. Through daily experiments, iterations, and missteps, she got comfortable with AI as a collaborator to support a design sprint. It accelerated every stage: synthesizing user feedback, generating divergent ideas, giving feedback, and even spinning up a working prototype, as shown below.

What was clear by Friday was that speed isn’t insight. While AI produced outputs fast, it was Kate’s designerly skills — curiosity, empathy, observation, visual communication, experimentation, and most importantly, critical thinking and a growth mindset — that turned data and patterns into meaningful insights. She stayed in the driver’s seat, verifying claims, adjusting prompts, and applying judgment where automation fell short.

She started the week on Monday, overwhelmed, her confidence dimmed by uncertainty and the noise of AI hype. She questioned her relevance in a rapidly shifting landscape. By Friday, she not only had a validated concept but had also reshaped her entire approach to design. She had evolved: from AI-curious to AI-confident, from reactive to proactive, from unsure to empowered. Her mindset had shifted: AI was no longer a threat or trend; it was like a smart intern she could direct, critique, and collaborate with. She didn’t just adapt to AI. She redefined what it meant to be a designer in the age of AI.

The experience raised deeper questions: How do we make sure AI-augmented outputs are not made up? How should we treat AI-generated user feedback? Where do ethics and human responsibility intersect?

Besides a validated solution to their design sprint problem, Kate had prototyped a new way of working as an AI-augmented designer.

The question now isn’t just “Should designers use AI?”. It’s “How do we work with AI responsibly, creatively, and consciously?”. That’s what the next article will explore: designing your interactions with AI using a repeatable framework.

Poll: If you could design your own AI assistant, what would it do?

- Assist with ideation?

- Research synthesis?

- Identify customer pain points?

- Or something else entirely?

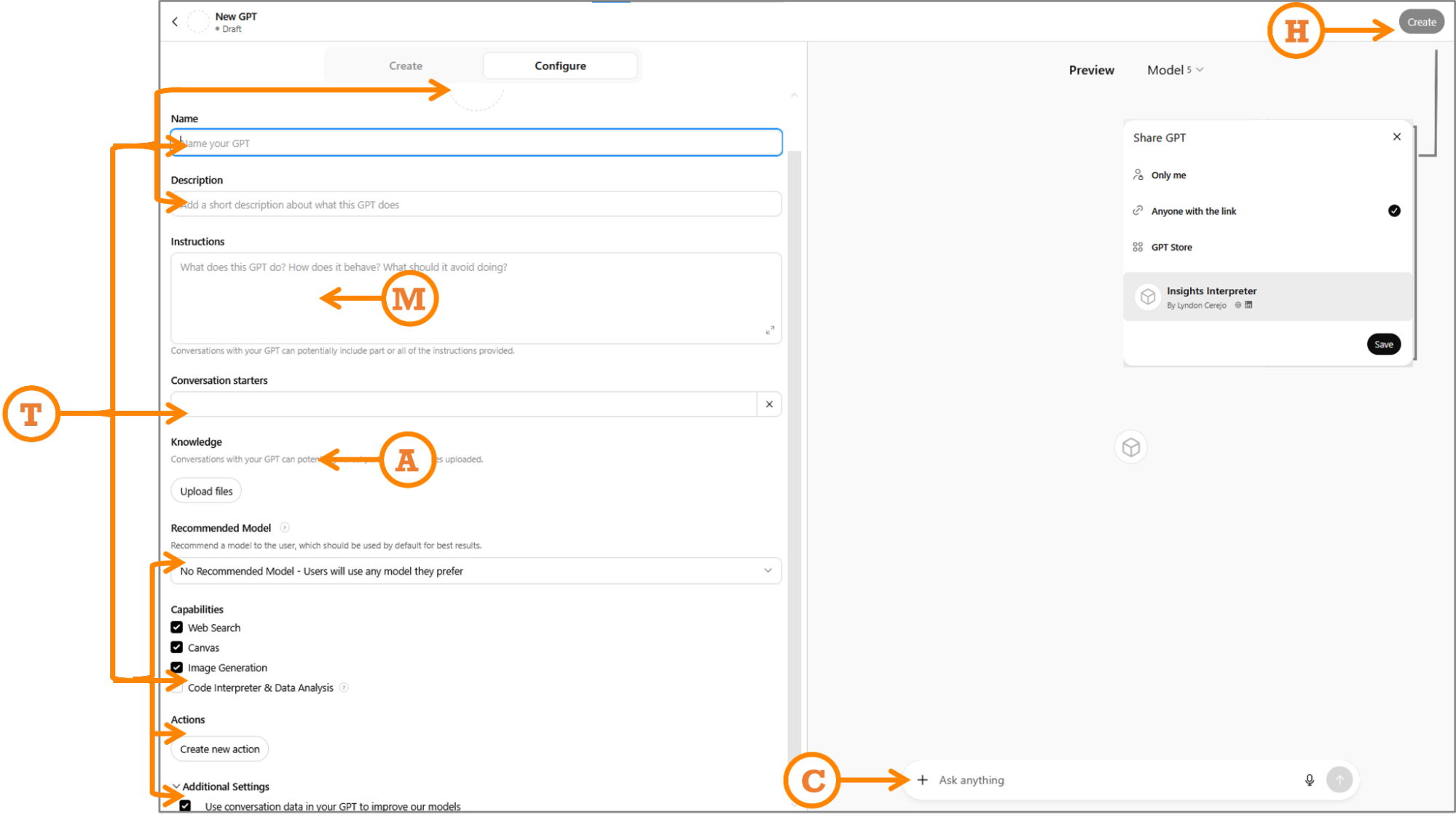

Share your idea, and in the spirit of learning by doing, we’ll build one together from scratch in the third article of this series: Building your own CustomGPT.

Resources

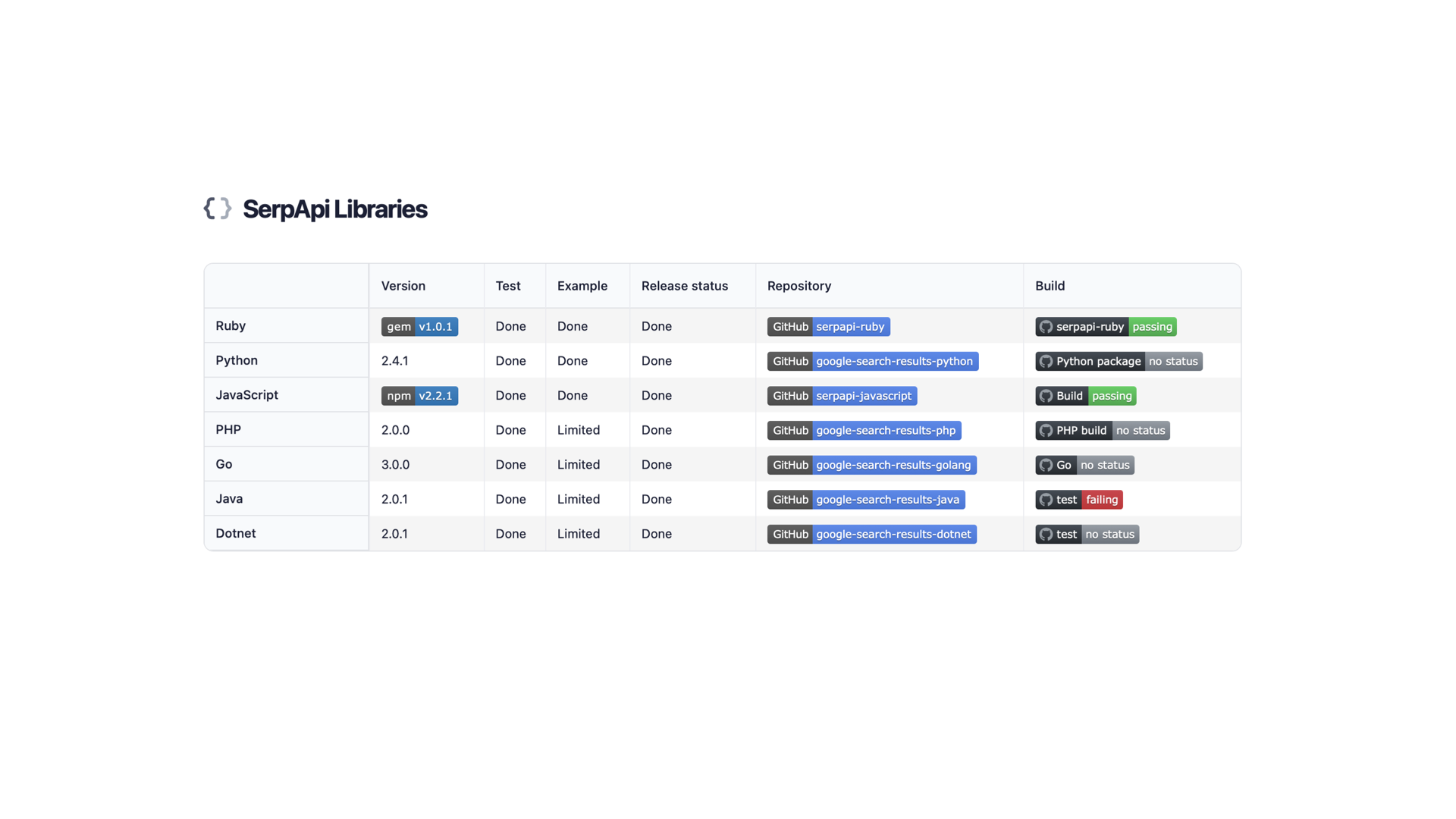

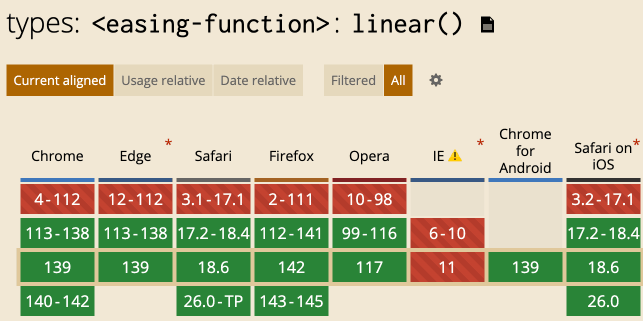

Tools

As mentioned earlier, ChatGPT was the general-purpose LLM Kate leaned on, but you could swap it out for Claude, Gemini, Copilot, or other competitors and likely get similar results (or at least similarly weird surprises). Here are some alternate AI tools that might suit each sprint stage even better. Note that with dozens of new AI tools popping up every week, this list is far from exhaustive.

| Stage |

Tools |

Capability |

| Understand |

Dovetail, UserTesting’s Insights Hub, Marvin |

Summarize & Synthesize data |

| Sketch |

Any LLM, Musely |

Brainstorm concepts and ideas |

| Decide |

Any LLM |

Critique/provide feedback |

| Prototype |

UIzard, UXPilot, Visily, Krisspy, Figma Make, Lovable, Bolt |

Create wireframes and prototypes |

| Test |

UserTesting, UserInterviews, PlaybookUX, Maze, plus tools from the Understand stage |

Moderated and unmoderated user tests/synthesis |